Among the most serious Earth science and environmental policy issues confronting society are the potential changes in the Earth’s water cycle due to climate change. The science community now generally agrees that the Earth’s climate is undergoing changes in response to natural variability, including solar variability, and increasing concentrations of greenhouse gases and aerosols. Furthermore, agreement is widespread that these changes may profoundly affect atmospheric water vapor concentrations, clouds, precipitation patterns, and runoff and stream flow patterns.

Global climate change will affect the water cycle, likely creating perennial droughts in some areas and frequent floods in others. (Photograph ©2008 Garry Schlatter.)

For example, as the lower atmosphere becomes warmer, evaporation rates will increase, resulting in an increase in the amount of moisture circulating throughout the troposphere (lower atmosphere). An observed consequence of higher water vapor concentrations is the increased frequency of intense precipitation events, mainly over land areas. Furthermore, because of warmer temperatures, more precipitation is falling as rain rather than snow.

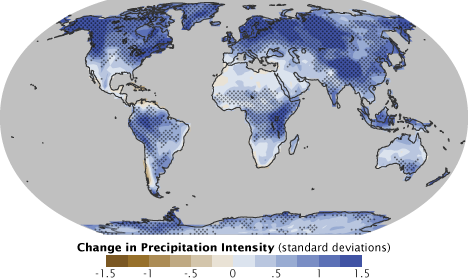

One expected effect of climate change will be an increase in precipitation intensity: a larger proportion of rain will fall in a shorter amount of time than it has historically. Blue represents areas where climate models predict an increase in intensity by the end of the 21st century, brown represents a predicted decrease. (Map adapted from the IPCC Fourth Assessment Report.)

In parts of the Northern Hemisphere, an earlier arrival of spring-like conditions is leading to earlier peaks in snowmelt and resulting river flows. As a consequence, seasons with the highest water demand, typically summer and fall, are being impacted by a reduced availability of fresh water.

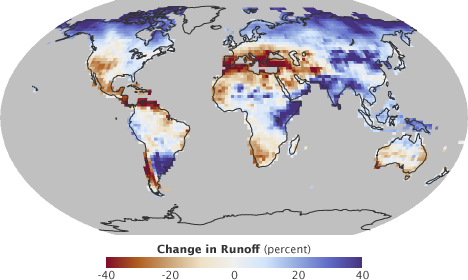

Changes in water runoff into rivers and streams are another expected consequence of climate change by the late 21st Century. This map shows predicted increases in runoff in blue, and decreases in brown and red. (Map by Robert Simmon, using data from Chris Milly, NOAA Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory.)

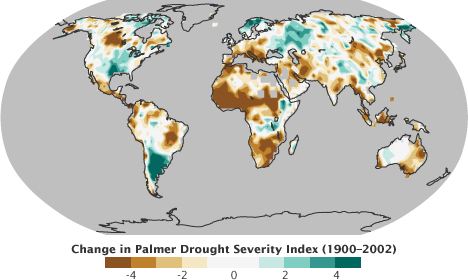

Warmer temperatures have led to increased drying of the land surface in some areas, with the effect of an increased incidence and severity of drought. The Palmer Drought Severity Index, which is a measure of soil moisture using precipitation measurements and rough estimates of changes in evaporation, has shown that from 1900 to 2002, the Sahel region of Africa has been experiencing harsher drought conditions. This same index also indicates an opposite trend in southern South America and the south central United States.

Shifts in the water cycle occurred over the past century due to a combination of natural variations and human forcings. From 1900 to 2002, droughts worsened in Sub-Saharan and southern Africa, eastern Brazil, and Iran (brown). Over the same period western Russia, south-eastern South America, Scandinavia, and the southern United States had less severe droughts (green). (Map adapted from the IPCC Fourth Assessment Report.)

While the brief scenarios described above represent a small portion of the observed changes in the water cycle, it should be noted that many uncertainties remain in the prediction of future climate. These uncertainties derive from the sheer complexity of the climate system, insufficient and incomplete data sets, and inconsistent results given by current climate models. However, state of the art (but still incomplete and imperfect) climate models do consistently predict that precipitation will become more variable, with increased risks of drought and floods at different times and places.