Drought and Dams |

|||

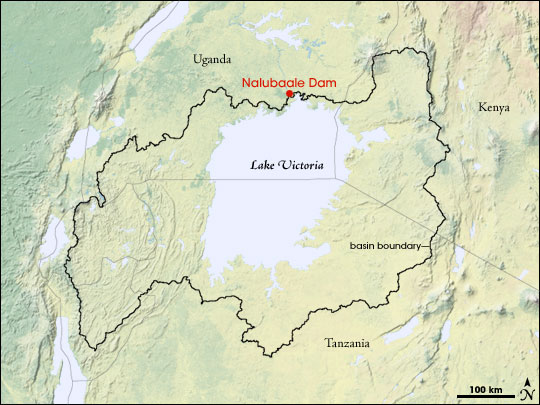

The leaps and plunges in water levels happen because of Lake Victoria’s hydrology. “Lake Victoria is unique because the lake [itself] is a large majority of its rain basin,” Reynolds explains. For most lakes, the rain that falls over a broad region flows into the lake through rivers, streams, and ground water. But Lake Victoria does not get water from a broad land region; most of its water comes from rain that falls directly over the huge lake. For this reason, the lake is very sensitive to rainfall, its water levels jumping depending on how much rain falls in a particular year. |

|||

| |||

Low rainfall accounts for some of the drop in water levels on Lake Victoria. Drought gripped several regions in Eastern Africa and the short rainy season, from October to December, was even more dismal in the Lake Victoria region. But drought alone may not account for the drastic drop in water levels on Africa’s largest lake. |

Lake Victoria’s rain basin (black border) is small relative to the size of the lake, leading to rapid fluctuations in lake level. (NASA image by Robert Simmon, based on the National Park Service Natural Earth map.) | ||

|

| ||

“Lake Victoria is operated as a reservoir,” says Reynolds. The White Nile River is the only outlet from the lake, and since 1954, the Owens Falls Dam [now Nalubaale] has controlled the flow of water out of Lake Victoria into the Nile according to the terms of a treaty between Uganda and Egypt. The policy, which was revised in 1964, ensured that the natural flow of the Nile River would not be impacted by the dam. Since the treaty, the Nalubaale Dam has operated to keep water levels near 11.9 meters above the Jinja gauge, and for 50 years, the policy successfully maintained water levels in Lake Victoria. |

Rainfall (dark green line) over Kisumu, Kenya, on the shores of Lake Victoria was modestly below average (light green fill) in the second half of 2005, but may not have been low enough to account for the large drop in lake levels. (NASA image by Robert Simmon, based on data provided by the USDA Foreign Agricultural Service.) | ||

But in an effort to bring more power to its developing economy, Uganda expanded the Nalubaale Dam in 2000, adding the Kiira power station to the dam. Almost immediately, drought struck, and officials were faced with both less water to generate power and a rising demand for electricity. When water levels on Lake Victoria plunged at the end of 2005, news media began reporting that water officials and environmental groups had accused the power authority that operates the dam of taking more water than the policy allowed. According to news reports in January 2006, Uganda’s Directorate of Water Development (DWD) reported that the primary cause for falling lake waters was the power company’s failure to adhere to the 1954 water release policy, but other government officials later denied these allegations, saying that the drought was the only reason water levels were falling. Regardless of the cause, the drop in water levels means that those who rely on the lake face some difficult choices. “Reservoirs have multi-uses, and economic value can be placed on these different uses,” says Reynolds. “You have to decide which economic use is going to take highest priority during dry periods.” With Lake Victoria, the choice is complicated. The lake is a crucial resource to the more than 30 million people in Uganda, Tanzania, and Kenya who live near its shoreline. It provides an inexpensive way to transport goods between the three countries. Its fish are an important source of food, and the lure of the lake, the evasive source of the Nile, draws tourists to its shores. |

Nalubaale Dam regulates the flow of water out of Lake Victoria and into the Nile River. Increased discharges of water from the dam for power production may be causing the water level of Lake Victoria to drop. (Photograph courtesy USDA Foreign Agricultural Service.) | ||

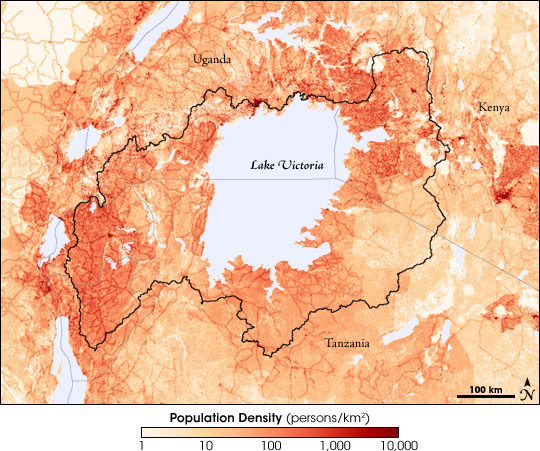

Though the lake has long served these purposes, the extent to which people are relying on the lake is unprecedented. Since 1960, when water levels on the lake jumped due to heavy rains, the population surrounding the lake has sky-rocketed. The Lake Victoria region has the densest rural population in the world, and population growth around the lake continues to increase faster than anywhere else in Africa. The current economy—fisheries, transport, resorts, and even the Nalubaale Dam Complex—has developed to operate around a much fuller Lake Victoria. |

Declining water levels in Lake Victoria are disrupting shoreline infrastructure like this small dock. (Photograph courtesy USDA Foreign Agricultural Service.) | ||

| |||

|

“Now they have to shut down the dams and they will have less hydropower generation,” says Reynolds, pointing out a newspaper article that reported that the Kiira extension to the Nalubaale Dam will be closed. “This [the drop in the water level] places additional costs onto the other economic users.” Ships have to dock in deeper water far from the shore; beach-side resorts are a long walk from the water; and the shallow alcoves where some fish breed are gone. “What is the best operation?” Reynolds muses. “Future water releases will need to follow the 1954 policy, but first water releases need to be reduced to allow the lake to return to pre-2000 water levels.” However, he sounds as if he does not envy the task because he knows towns, governments, and power companies want more energy. Will government policies allow the lake to return to levels experienced before 2005? To answer that question, “the USDA and NASA will continue to monitor the water levels, and we can quickly report to the international community whether any progress has been made,” says Reynolds.

|

The area around Lake Victoria is the most densely populated rural region in the world. The region’s 30 million residents rely on the lake for food, transportation, power, and income from tourism. Beige colors on this map represent areas of low population density, while dark red areas represent high population density. (NASA image by Robert Simmon, based on data provided by the USDA Foreign Agricultural Service.) | ||