| |

Given the vast area and the less-than-optimal field conditions, satellite

sensors provided a good alternative to canvassing this sometimes dangerous

terrain on the ground. “Obviously,” says Tucker, “you can’t

see locusts from satellites. But swarm development is closely tied to rainfall

and green vegetation, which we can detect from space. Detecting a patch of green

vegetation on a satellite image where there was previously only bare soil is a

straightforward way to monitor the locust habitat,” explains Tucker.

“When we see vegetation springing up in the desert, we know where

conditions are right for an outbreak, and we can direct ground survey crews to

exactly the right spot to investigate.”

|

|

|

| |

Field biologists exploring potential hot spots located by satellites are looking

for more than just a large number of locusts. They are also looking for evidence

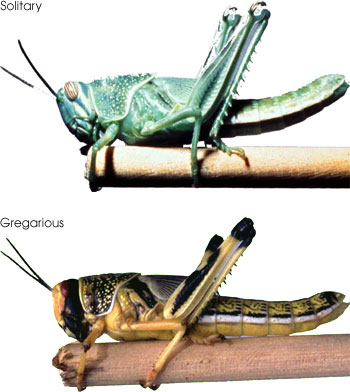

of something akin to a split personality. Says Tucker, “The desert locust

has two phases. In one phase, it’s reclusive and solitary, going out of its

way to avoid coming into contact with another of its kind and migrating only at

night. But the locust also has this sort of alter ego where it undergoes

explosive population growth, changes color and shape, and becomes more tolerant

of others, more social, or gregarious.”

So what causes harmless desert locusts to break all the bounds of normal social

restraint and form a swarming, marauding mob? In a word: water. That most

precious of desert resources, rainfall can transform a barren desert landscape

with a blush of ephemeral green vegetation. It also moistens the sandy soils

where the desert locust lays its eggs. The moisture initiates the hatching of

the eggs and causes vegetation to grow. The newly grown vegetation increases the

food supply and provides shelter for the newly hatched “hoppers,” as

the young, wingless insects are called. At roughly weekly intervals, depending

on temperature, the hoppers molt, finally achieving adult, winged status after

five cycles.

The default state of the desert locust is to be solitary—to have a strong

aversion to others of its kind. But when rains spur egg development and

vegetation, the population of locusts grows rapidly. Given enough vegetation and

a big enough area, the locusts might be expected to spread out. But when

vegetation is distributed on the landscape in such a way that the locusts have

to congregate in order to feed or if conditions are so good in a particular area

that great numbers of locusts are hatched, the locusts abandon their solitary

instincts.

|

|

Flushes of vegetation in remote desert

wadis attract normally solitary locusts into confined areas. If conditions are right

the locust population explodes, and the locusts undergo a transformation from desert

loners to swarming hordes. (Photograph courtesy Compton Tucker, NASA GSFC)

|

| |

The forced physical contact brought about when numerous locusts descend on a

dwindling food supply causes the animals’ hind legs to bump up against one

another. This jostling triggers a cascade of metabolic and behavioral changes

that signal the insect’s transformation from “go it alone” to

“one of the crowd.” They develop a yellow and black warning

coloration—most pronounced in the juveniles—that notifies potential

predators that they have been munching on poisonous plants. Their bodies become

shorter, and they give off a perfume of hormones that causes them all to be

attracted to the same location, which enhances swarm formation.

A dramatic increase in a localized population often signals an outbreak, which

can die out or persist, depending on the continuation of favorable conditions.

When outbreaks persist in the same or nearby area, the event has progressed to

an “upsurge.” If the upsurge fails to die out quickly, it can rapidly

increase in size, and then a plague, or swarm, is underway. The swarm advances

far outside its natural habitat, called the recession area, and migrates en

masse, sometimes thousands of kilometers.

|

|

Solitary locusts are distinct from

gregarious locusts in their coloration, shape, scent, and behavior. The most dramatic color changes occur among

juveniles (these pictures). In mature adults, the color change is normally from brown to yellow. (Photograph

courtesy Compton Tucker, NASA GSFC)

|

| |

The changes in appearance and behavior are so profound that despite humans’

long relationship with the insect, it wasn’t until 1921 that scientists

even became aware that the standoffish locust of the recession years was the

same species of insect that exploded out of the desert, devouring crops and

native vegetation and leaving devastation and famine it its wake.

Finding the Hot Spots Finding the Hot Spots

The Reach of the Desert Locust The Reach of the Desert Locust

|

|

Swarming locusts range far and

wide—as far as Portugal, the Congo, Afghanistan (this photograph), and

Bangladesh. (Photograph courtesy Compton Tucker, NASA GSFC) |