Before man-made satellites were invented, monitoring enough glaciers to get a

measure of global climate change would have been impossible, said Hall.

Some glaciers tend to extend in many different directions. As they melt, one part

may retract and another part may stay put. Between 1973 and 1987, many outlet glaciers

of the Vatnajökull ice cap in Iceland has been steadily receding.

Yet, parts of the glacier haven't moved at

all (Hall et al. 1992). If scientists were to travel to the glacier and

measure just this section, they could be deceived. Measurements have to be made

regularly at every extension of the ice cap to see if the glacier as a whole is

melting, Hall said. While this may be feasible for one glacier, it is nearly

impossible to measure a hundred glaciers this way. Before man-made satellites were invented, monitoring enough glaciers to get a

measure of global climate change would have been impossible, said Hall.

Some glaciers tend to extend in many different directions. As they melt, one part

may retract and another part may stay put. Between 1973 and 1987, many outlet glaciers

of the Vatnajökull ice cap in Iceland has been steadily receding.

Yet, parts of the glacier haven't moved at

all (Hall et al. 1992). If scientists were to travel to the glacier and

measure just this section, they could be deceived. Measurements have to be made

regularly at every extension of the ice cap to see if the glacier as a whole is

melting, Hall said. While this may be feasible for one glacier, it is nearly

impossible to measure a hundred glaciers this way.

Satellite sensors

such as those on Landsat 5 and Landsat 7 allow scientists to measure the entire

rim of any glacier on an annual basis, cloud cover permitting. These satellites each have seven

different types of light detectors (photoreceptors) on board, which acquire

images of different wavelengths of sunlight being reflected off of the Earth.

One light detector records only the blue light coming off the Earth (band 1).

Another observes all the yellow-green light (band 2) and still another picks up

on all the near-infrared light (band 4). The satellites move in circular

orbits, very nearly from pole-to-pole, around the Earth and scan strip after

strip of our spinning planet. The satellites’ images are then beamed back

to the surface, where Hall and other researchers can examine them.

Using satellites to watch glaciers Using satellites to watch glaciers

Types of glaciers Types of glaciers

|

|

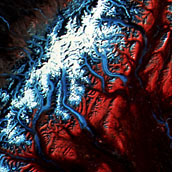

False color satellite

image of the glaciers surrounding Mount McKinley, Alaska. Landsat, August 24, 1979.

Glaciers are blue, clean snow is white, vegetation is red and bare rock is brown. (Image courtesy

Dorothy Hall, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center) |