Rules of Engagement | |||

In December 2004, the traverse team found itself stalled near the base of the Transantarctic Mountains. Everyone had known they would encounter crevasses, but no one had anticipated the sheer number of them. Except for the route they had taken into the crevasse field, the team members couldn’t find a reliable way out. |

|||

| |||

In the field, Antarctic researchers and technicians use a couple of different methods for detecting crevasses. One is to drive over the terrain in a lightweight snowmobile equipped with radar that can sense open spaces under the snow. Such a light vehicle isn’t likely to exert enough pressure to break through a snow bridge. Big, heavy vehicles like tractors use long booms on the front with ground-penetrating radar equipment mounted on them. The heavy vehicles move slowly enough to stop if the radar detects a crevasse. |

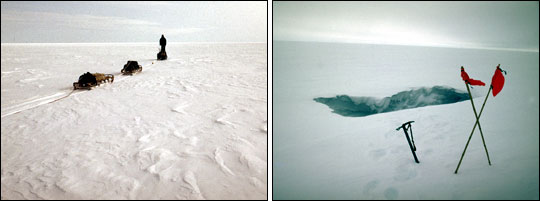

A researcher dragging a sled of gear scouts for crevasses on the Ross Ice Shelf (left). An exposed crevasse gapes at the surface. In front of the hole, someone has plunged two flagged poles and an ice axe (right). (Photos courtesy Ted Scambos, National Snow and Ice Data Center) | ||

“Likewise, at night when the team stops to camp, the ground-penetrating radar covers a 200-foot-diameter circle and surveys that entire area. The vehicle drives around in that circle, and that track can be fairly readily seen. That becomes the ‘safe area.’ So at night, if people want to ski or walk around, or just sit out and read a book, that’s safe. They don’t go outside that ring,” says Blaisdell. |

Taken with a remote-controlled airplane, this picture shows the traverse team’s camp on the Antarctic Plateau, after a successful ascent of Leverett Glacier. Tracks in the snow outline the camp’s “safe” area. (Photo courtesy John Penny and The Antarctic Sun) | ||

“What we’re doing is extremely different than what Hillary or Scott or Amundson or some modern-day adventurers have done. We’re not doing this to say we’ve been someplace and had an adventure; we’re doing this to set up a system for routine supply of critical goods to the places that need them,” he says. “This is not about being a hero or taking risks.” The trek was organized, start to finish, to minimize that kind of drama. Although they were never in mortal danger, Blaisdell explains, the team was frustrated. At the base of the Transantarctic Mountains, the team’s forward progress ground to a halt as they encountered and avoided crevasse after crevasse. No one wanted to turn back; everyone wanted to cross the mountains. But even though they had the ability to keep themselves from tumbling into any crevasse in their path, they had no way of knowing which path would be the least trouble. What the team needed was a different perspective. |

At McMurdo Station, researchers trained to rescue each other from crevasses. Ted Scambos took this picture while waiting to be “rescued” from the void. (Photos courtesy Ted Scambos, National Snow and Ice Data Center) | ||