| A Widespread Problem |

| ||

Boreal forests, or northern evergreen forests that encircle the Earth above 48°N latitude, are second in areal extent only to the world’s tropical forests and they occupy about 21 percent of the world’s forested land surface (Sellers et al 1997). Together, the North American and Eurasian boreal ecosystems span about 14.3 million square km (Kasischke et al 1995). Hence, fighting fires across these vast landscapes is a big problem, particularly for the Canadian and Russian governments. It simply isn’t economically feasible to fight them all, and most fires are allowed to burn themselves out. Quite often, firefighters in those countries aren’t even aware of wildfires in remote regions until after they have been burning for days. Given their size and remoteness, satellite remote sensors are the only cost effective way of monitoring fires in the boreal regions. Firebombers

|

| ||

In the 1940s, Canadian firefighters began using airplanes—called "fire bombers"—to combat wildfires. Initially, they used latex-lined bags to make large "water bombs" that firefighters would drop through holes in the cabin onto their targets. By 1950s, the firebombers had been modified to allow them to scoop up water from nearby lakes so they could fly as many sorties over a wildfire as fuel permitted. While the use of aircraft greatly improved the speed and efficiency with which firefighters could extinguish wildfires, ironically, they helped create a new problem in some relatively small regions near parks and urban centers. Fire suppression allowed unusually large amounts of fuel (dead vegetation) to accumulate on the ground in those regions, thus creating a greater fire danger. Paradoxically, over the last 25 years, forest resource managers have begun to fight fire with fire. Increasingly, they are using fire as a tool to prevent wildfire—a technique called "prescribed burning." These small-scale fires both help clear away dead or dying vegetation for new growth as well as reduce the risk of larger, uncontrolled outbreaks later. In 1998, Canadian fire officials burned about 16,000 hectares (160 square km) in prescribed fires (Turner 1999). Additionally, Canadian officials allow some wildfires to burn in a controlled manner in areas where there is heavy fuel accumulation. Some Burning Issues

In Russia, however, the boreal wildfire problem is both more severe and

poorly documented. The Russian boreal region is larger than its Canadian

counterpart, thus there is a greater challenge of fighting fires across a wider

frontier. Consequently, the Russian government only actively suppresses fires

in roughly two-thirds of its boreal region, typically leaving the rest to burn

(Kasischke et al 1999). Moreover, scientists who monitor fires on a global

scale suspect that the Russians greatly underestimate the total area burned on

an annual basis due to the financial incentives that the government provides to

those regions that report good success at fire suppression (Kasischke et al

1999). |

| ||

Based upon analysis of AVHRR data, fire scientists estimate that roughly 12 million hectares (120,000 square km) of Eurasian boreal forest burned in 1987; and most of that was in areas actively monitored by Russian foresters (Kasischke et al 1999). This figure compares dramatically with the estimate of 1.27 million hectares burned reported by Russian officials (Kasischke et al 1999). Another point of contention between fire scientists is the type of fires that occur in the Russian boreal forests (Kasischke et al 1999). The Russians report that more than 95 percent of all fires burn at the surface; whereas North American foresters report that more than 90 percent of the fires in Alaska and Canada are "crown fires," or fires that burn up to the top of the forest canopy (Kasischke et al 1999). Fire scientists suspect that the Russian reports are inaccurate and that the relative number of crown fires is similar to the proportion they see in North America. Why is this significant? Because the type of fire is suggestive of its intensity and the efficiency with which it consumes biomass and releases emission products (smoke and gases). Surface fires generally consume less fuel—8 to 12 tons of biomass per hectare burned—and release lower amounts of smoke particles and greenhouse gases into the air (Kasischke et al 1999). Crown fires burn hotter, consume much more fuel—30 to 40 tons of biomass per hectare burned—and tend to release emission products much higher into the atmosphere where they are usually spread over much wider distances (Kasischke et al 1999). Emission products injected at higher levels in the atmosphere tend to remain in the air longer and have a greater effect on air quality in the surrounding region. Which fire estimates for the Russian boreal region are most accurate? Today, most fire scientists believe that the numbers derived from AVHRR and Landsat images are more accurate because when they compare images of fires in North America with images of fires in Russia, the spectral signatures (thermal infrared radiant energy) match closely (Kasischke et al 1999). Moreover, scientists point out, if the dense forest canopy was undamaged, then it would effectively mask the thermal energy from fires confined to the surface, so the satellites wouldn’t see them (Kasischke et al 1999).

|

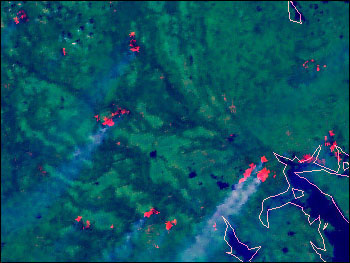

These fires burned to the east of St. Petersburg, Russia, in August of 1998. Red represents the heat of fires, while smoke appears blue. This image was aquired by the Advanced Very High Resolution Radiometer (AVHRR) aboard NOAA's polar orbiting weather satellites. (Image by NOAA Operational Significant Event Imagery) |