Arctic sea ice likely reached its annual minimum extent on September 19 and again on September 23, 2018, according to researchers at the National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC) and NASA. Analyses of satellite data showed that the Arctic ice cap shrank to 4.59 million square kilometers (1.77 million square miles), tied for the sixth lowest summertime minimum on record. Researchers at NSIDC noted that the estimate is preliminary, and it is still possible (but not likely) that changing winds could push the ice extent lower.

Arctic sea ice follows seasonal patterns of growth and decay. It thickens and spreads during the fall and winter and thins and shrinks during the spring and summer. But in recent decades, increasing temperatures have led to significant decreases in summer and winter sea ice extents. The decline in Arctic ice cover will ultimately affect the planet’s weather patterns and the circulation of the oceans.

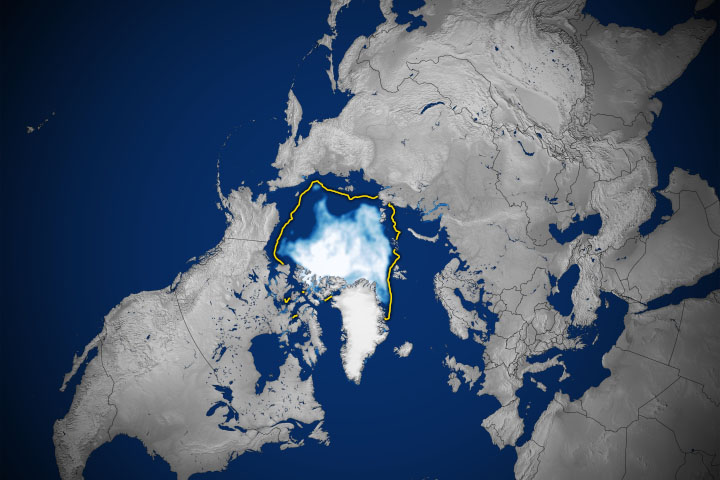

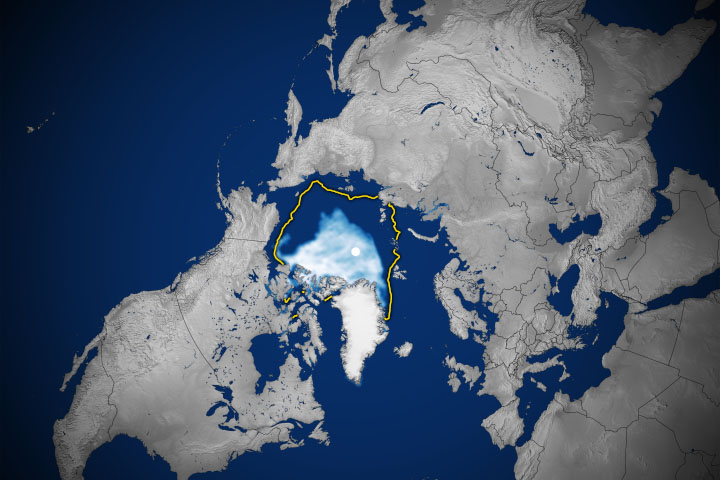

The map above shows the extent of Arctic sea ice as measured by satellites on September 19, 2018. Extent is defined as the total area in which the ice concentration is at least 15 percent. The yellow outline shows the median September sea ice extent from 1981–2010. The second image is a mosaic that was compiled by the Canadian Ice Service using data collected between September 18 and 24 by the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) instruments on NASA’s Aqua and Terra satellites.

The 2018 minimum is 1.63 million square kilometers (629,000 square miles) below the 1981–2010 average ice minimum. NASA scientists Claire Parkinson and Nick DiGirolamo have calculated that Arctic sea ice has lost roughly 54,000 square kilometers (21,000 square miles) of ice for each year since the late 1970s—equivalent to losing a chunk of sea ice the size of Maryland and New Jersey for every year.

Arctic weather conditions this summer were a mixed bag, with some areas experiencing warmer-than-average temperatures and rapid melting, while other regions remained cooler than normal. One of the most unusual features of this year’s melt season has been the reopening of a polynya-like hole in the icepack north of Greenland, where the oldest and thickest sea ice of the Arctic typically resides.

“The combination of thin ice and southerly warm winds helped break up and melt the sea ice in this region,” said Melinda Webster, a sea ice researcher at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center. “This opening matters for several reasons. For starters, the newly exposed water absorbs sunlight and warms the ocean, which affects how quickly sea ice will grow in the following autumn. It also affects the local ecosystem, such as seal and polar bear populations that rely on thicker, snow-covered sea ice for denning and hunting.”

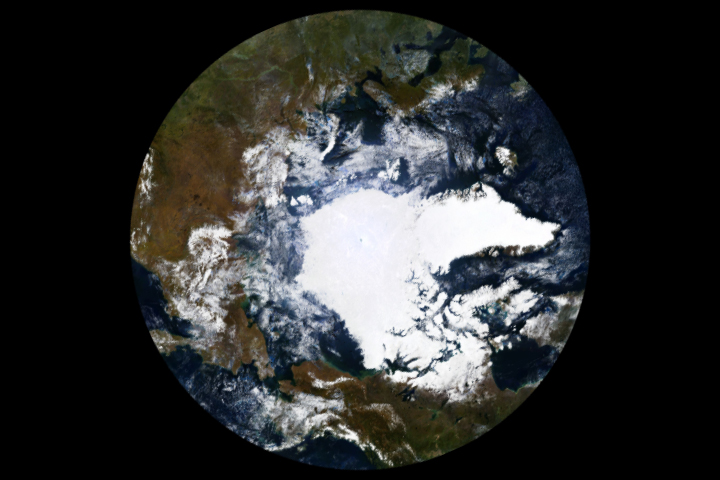

On October 24, NASA will mark the 40th anniversary of the launch of the Nimbus 7 satellite, which began the long-term, consistent record of measurements of polar ice extent and distribution from space.

“In view of the significant regional and interannual variability, if we didn’t have the satellite record there would be a great deal of uncertainty as to what the full change in the Arctic sea ice cover has been,” Parkinson said. “But the 40-year record of satellite measurements reveals quite definitively that the Arctic sea ice coverage has decreased substantially.”

NASA Earth Observatory image by Joshua Stevens, using data from the National Snow and Ice Data Center. Polar mosaic courtesy of the Canadian Ice Service. Story by Maria–José Viñas, NASA’s Earth Science News Team, with Mike Carlowicz, NASA Earth Observatory.

Image of the Day Water Snow and Ice Remote Sensing Sea and Lake Ice

The ice cap tied for the sixth lowest extent on record, continuing a long-term decline.

Image of the Day for September 28, 2018

Every year, the frozen seawater in the Arctic Ocean and around Antarctica reaches a maximum and minimum extent.