The Soil Moisture Active Passive mission (SMAP) was launched in 2015 as the first NASA satellite dedicated to measuring the water content of soils. The satellite uses a radiometer to measure soil moisture in the top 5 centimeters of the ground. It is a small amount of water on a global scale, but it is critical for farmers trying to figure out when, where, and what to plant.

Thanks to tools developed by researchers at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, SMAP soil moisture data is now being used by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) Foreign Agricultural Service, which monitors global croplands and makes crop forecasts. Variations in global agricultural productivity have tremendous economic, social, and humanitarian consequences.

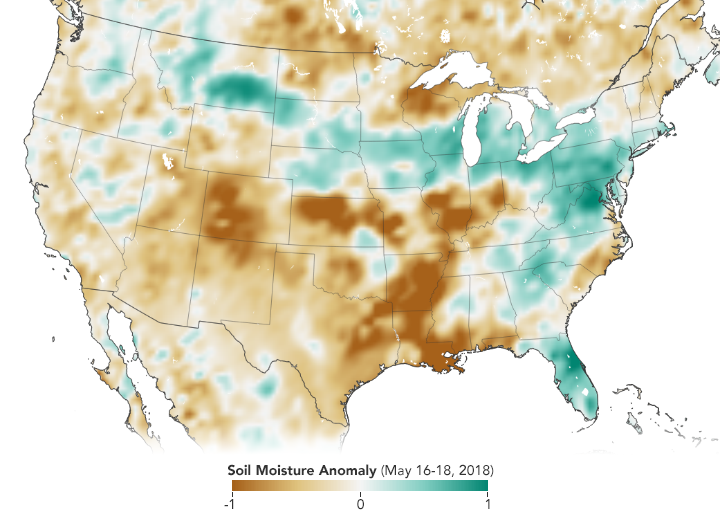

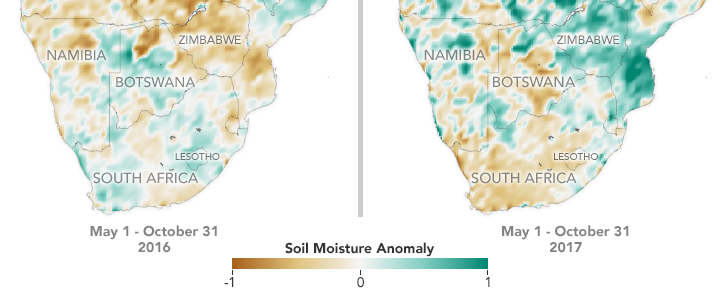

For three years, SMAP has helped map the amount of water contained in soils worldwide across months and seasons. Now those data are being applied on regional and local scales. The map above, based on SMAP data, shows soil moisture anomalies—how much the moisture content was above or below the norm—in the United States in mid-May 2018. The second map depicts anomalies and how they changed in southern Africa from 2016 to 2017.

“If you have better soil moisture data and information on anomalies, you’ll be able to predict, for example, the occurrence and development of drought,” said Iliana Mladenova, a research scientist who helped develop the tools along with John Bolten at NASA Goddard.

SMAP data are being incorporated into USDA’s Crop Explorer website, a clearinghouse for global agricultural growing conditions such as soil moisture, temperature, precipitation, and vegetation health. USDA regional crop analysts need accurate soil moisture information to better predict where there could be too little or too much water in the soil to support crops.

The USDA currently uses computer models that incorporate precipitation and temperature observations to indirectly calculate soil moisture. This approach, however, is prone to error in areas lacking high-quality, ground-based instrumentation. Mladenova noted that by incorporating direct SMAP measurements into Crop Explorer, agriculture analysts can help fill in the gaps.

The timing of the information matters. If there is a short dry period early in the season, it might not have an impact on the total crop yield. But if there is a prolonged dry spell when the grain should be forming, the crop is less likely to recover. With global coverage every three days, SMAP can provide the Crop Explorer tool with timely updates on soil moisture conditions.

SMAP and USDA data, along with tools to analyze it, are also available on Google Earth Engine for researchers, nonprofits, resource managers, and others who need the information.

For more than a decade, the USDA Crop Explorer has incorporated soil moisture data from satellites. It started with the Advanced Microwave Scanning Radiometer-E instrument aboard NASA’s Aqua satellite, but that instrument stopped gathering data in late 2011. Soil moisture information from the European Space Agency’s Soil Moisture and Ocean Salinity (SMOS) mission is also being incorporated into some USDA products.

NASA Earth Observatory images by Joshua Stevens, using soil moisture data courtesy of Nazmus Sazib/NASA GSFC and the SMAP Science Team. Story by Kate Ramsayer, NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, with Mike Carlowicz, NASA Earth Observatory.