Today’s story is the answer to the May 2024 puzzler.

Greenhouses are having a moment—or rather, a few decades. According to a new analysis of satellite data published in Nature Food, greenhouses now cover more than 13,000 square kilometers (5,000 square miles) of land worldwide—an area nearly the size of Connecticut. Four decades ago, they covered just 300 square kilometers.

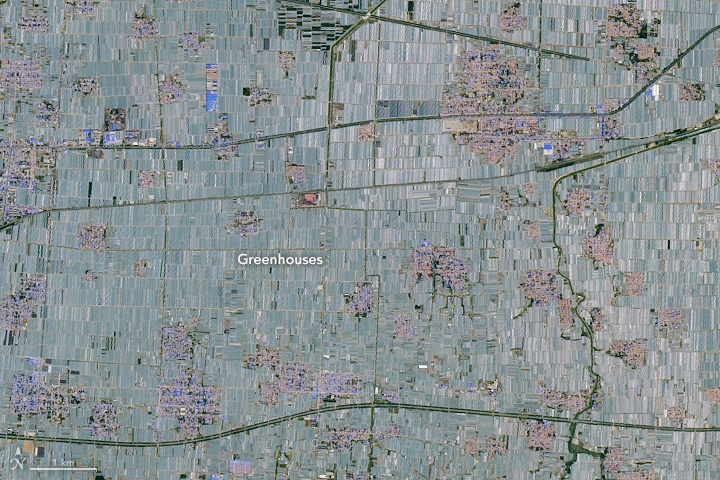

The most expansion occurred in China, now home to 60 percent of the world’s greenhouses. The structures can be found on farmland in several Chinese provinces and across a range of climates, but they are most concentrated in the North China Plain—a large alluvial plain west of the Yellow and Bohai seas. The largest cluster of greenhouses in China, and the world, spreads across more than 820 square kilometers of this plain in Weifang, a prefecture-level city in Shandong Province in northeastern China.

The pair of Landsat images above highlights the rapid expansion of greenhouses in Weifang. The image on the left, acquired by the TM (Thematic Mapper) on Landsat 5, shows Weifang in 1987; the image on the right, from the OLI (Operational Land Imager) on Landsat 8, shows the same area in 2024. Large expanses of once-open farmland are now covered by a sea of plastic. Many of the greenhouses have opaque or translucent plastics that appear white from a distance, while open farmland is generally brown or green. Towns appear slightly blue or pink due to the colors of roofs.

In this part of China, fruits and vegetables are generally grown in the greenhouses. “Cucumbers, eggplants, and tomatoes provide off-season vegetables to the whole country,” said Xiaoye Tong, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Copenhagen and an author of the study. “Increasingly, farmers in Weifang are also planting high-value fruits, such as strawberries, grapes, kiwi, and dragon fruit.”

Farmers use plastic greenhouses because they are an effective and relatively inexpensive way to increase yields. They can be used to extend the growing season and exert control over temperature and lighting conditions. Innovations such as drip irrigation, the use of artificial soil, and hydroponics have added to the popularity of greenhouse cultivation.

Domestic demand for produce has likely helped stir the greenhouse boom, according to the team of University of Copenhagen researchers. China’s total production of tomatoes, cucumbers, and gherkins increased sixfold between 1990 and 2020, even though exports stayed roughly the same.

The researchers used high-resolution satellite imagery from Planet Labs and the European Sentinel-2 satellite constellation to map greenhouses in 2019, the most recent year they analyzed. To track longer-term changes, they relied on imagery from Landsat, a USGS/NASA satellite program that has been operating since the 1970s. As part of the analysis, the researchers used Landsat images to identify the year when greenhouse construction first appeared in each of the 65-largest clusters of greenhouses. They also tracked changes (between 1985 and 2021) in the largest greenhouse clusters in the five countries with the most greenhouse area: Weifang, China; Almería, Spain; Bari, Italy; Antalya, Türkiye; and Chapala, Mexico.

“The rate of expansion is the most dramatic in China, but the increase is a global phenomenon,” Tong said. The researchers mapped greenhouses in 119 countries, including Spain (5.6 percent of the total greenhouse area), Italy (4.1 percent), Mexico (3.3 percent), Türkiye (2.4 percent), Morocco (2.3 percent), the Republic of Korea (1.8 percent), Japan (1.7 percent), the Netherlands (1.4 percent) and France (1.3 percent). They also mapped greenhouses in 22 countries in Africa, where they are primarily used for vegetable and cut flower production.

The team’s mapping of greenhouse cultivation is one of the most detailed and comprehensive researchers have conducted to date. Earlier assessments of the global extent of greenhouses have been based on industry reports and have not included georeferenced information on the exact locations of greenhouses.

“Our hope is that the detailed, georeferenced information we’re providing from satellites will be useful to policymakers, local and international development organizations, industry stakeholders, and farmers,” Tong said, “as they balance the benefits of increases in production made possible by greenhouses along with the environmental impacts of land cover change and plastic pollution.”

NASA Earth Observatory image by Lauren Dauphin, using Landsat data from the U.S. Geological Survey. Story by Adam Voiland.