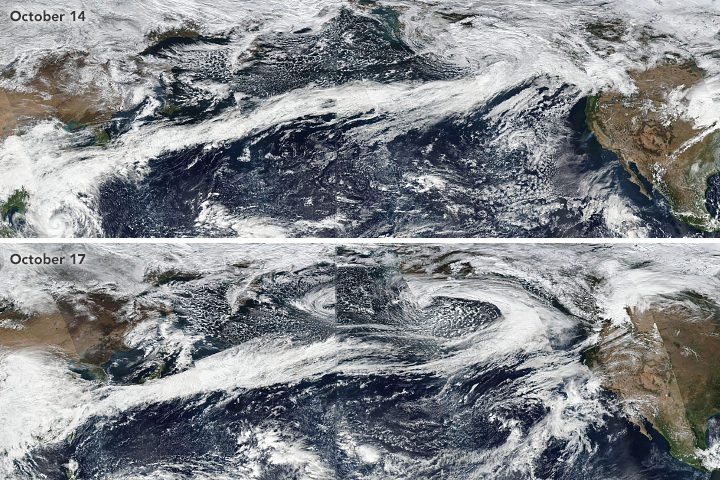

Atmospheric rivers stretched from Asia to North America in October 2017. Learn more.

If you live on the West Coast of North America, you have probably heard meteorologists talk about “atmospheric rivers” — the narrow, low-level plumes of moisture that often accompany extratropical storms and transport large volumes of water vapor across long distances. When atmospheric rivers encounter land, they can drop tremendous amounts of rain and snow. That can be good for replenishing reservoirs and for quenching droughts, but these remarkable meteorological features can also trigger destructive floods, landslides, and wind storms.

During the past decade, atmospheric rivers have fueled a flood of another type: scientific research papers. Prior to 2004, fewer than 10 studies mentioned atmospheric rivers in any given year; in 2015, about 200 studies were published on the matter. The availability of increasingly sophisticated satellite and aircraft data has fueled the trend, according to a recent article in the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. Here’s a sampling of what scientists have learned about these rivers in the sky.

They Can Bring Rains, Winds, And Lots of Damage

In a study led by Duane Waliser of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory and published in Nature Geoscience, researchers showed that atmospheric rivers are among the most damaging storm types in the middle latitudes. Of the wettest and windiest storms (those ranked in the top 2 percent), atmospheric rivers were associated with nearly half of them. Waliser and colleagues found that atmospheric rivers were associated with a doubling of wind speed compared to all storm conditions.

They Shift With The Seasons

During the winter, atmospheric rivers in the Pacific generally shift northward and westward, Bryan Mundhenk of Colorado State University and colleagues concluded in a study. They also found that the El Niño/Southern Oscillation (ENSO) cycle can affect the frequency of atmospheric river events and shift where they occur. The research was based on data processed by MERRA, a NASA reanalysis of meteorological data from satellites.

They Aren’t Just a West Coast Thing

Atmospheric rivers are a global phenomenon and responsible for about 22 percent of all water runoff. One recent study from a University of Georgia team underscored that the U.S. Southeast sees a steady stream of atmospheric rivers. “They are more common than we thought in the Southeast, and it is important to properly understand their contributions to rainfall given our dependence on agriculture and the hazards excessive rainfall can pose,” said Marshall Shepherd of the University of Georgia. Other studies note that atmospheric rivers have contributed to anomalous snow accumulation in East Antarctica and extreme rainfall in the Bay of Bengal.

Climate Change Could Alter Them

A recent study led by Christine Shields of the National Center for Atmospheric Research suggests that climate change could push atmospheric rivers in the Pacific toward the equator and bring more intense rains to southern California. The modeling calls for smaller increases in rain rates in the Pacific Northwest. Another ensemble of models shows a in the number of days with landfalling atmospheric rivers in western North America.

Satellites Are Key to Studying Their Precipitation

While there are few ground-based weather stations in the open ocean to tally how much rain falls, satellites such as those included in the Global Precipitation Measurement (GPM) mission can estimate precipitation rates from above. “Satellites have proven valuable over both the ocean and land, though uncertainties are often larger over land because of complicating factors like the terrain and the presence of snow on the surface,” said Ali Behrangi, the author of a study that assessed the skill of different satellite-derived measurements of precipitation rates.