Faunal Succession’s LegacyAlthough it might seem surprising, Smith’s principle of faunal succession didn’t provide an immediate understanding of the history of life on Earth, perhaps because his intentions were more practical than scientific: to accurately order rock layers and to help coal prospectors identify the best places to dig. A generation later, John Phillips, Smith’s nephew and biographer, went on to name the major eras in today’s geologic timescale: Paleozoic (ancient life), Mesozoic (middle life), and Cenozoic (new life). These periods were based on the fossil record, much of it documented by Smith. |

|||

| |||

“The Geologic Timescale is the Principle of Fossil Succession at its best,” says Jaelyn Eberle. Curator of vertebrate paleontology and assistant professor of geology at the University of Colorado-Boulder, Eberle teaches her students about how the divisions within the geologic timescale are all based on fossil turnovers in the rock record—periods when species of plants and animals went extinct or originated. Before radiometric dating enabled geologists to apply absolute dates to rocks, she explains, dating rock layers relative to each other based on their fossils was the best method available. And because not every rock can be dated radiometrically, relative dating with fossils continues—and in fact, it predominates—today. “All of us are using the Principle of Faunal Succession,” she says. |

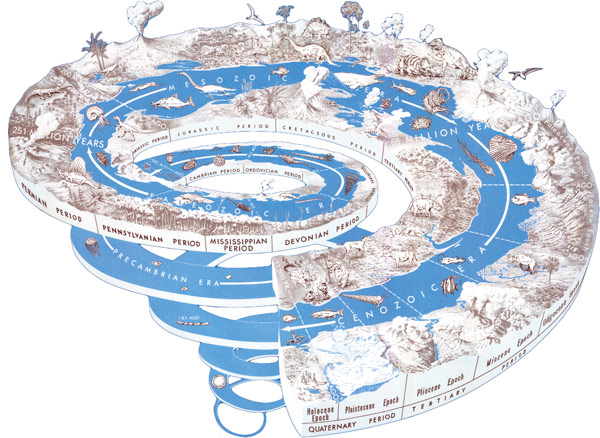

William Smith’s discovery of faunal succession was one of the keys to unlocking deep time. The history of Earth stretches far beyond the 6,000-year recorded history of civilization, the origin of Homo sapiens 200,000 years ago, the first appearance of mammals 164 million years ago, or even the origin of hard-shelled animals 543 million years ago. (Diagram courtesy USGS.) | ||

| |||

Fossils don’t just allow scientists to date rock layers, but also to uncover past climates, some of which differ dramatically from today’s. One of the best examples is the Eocene Epoch, roughly 55 to 34 million years ago. Although the continents were mostly in the same position then that they are today, Eberle has dug Eocene fossils in the Arctic and found a surprising collection of warm-weather fauna. “We’ve found fossils of alligators, turtles, tapirs, even primates,” she says. Fossil plants also left evidence of a warmer climate. Eocene coal seams—compressed, old swamps—are abundant in the Arctic, as are ancient tree trunks and leaf impressions. Fossil succession has helped scientists to understand that not only has Earth’s climate changed throughout history, the ground itself has shifted across the planet’s surface. Among the evidence that Alfred Wegener provided for his theory of continental drift was that rock strata laid down at the same time in Africa and South America contained identical fossils—even though today they are on opposite sides of the Atlantic. The influence of faunal succession would also eventually affect biology. Although Charles Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace would not propose the theory of natural selection until after Smith’s death, Smith’s work enabled geologists and biologists of subsequent generations to think in terms of long expanses of time—a necessary ingredient for Darwinian evolution to occur. |

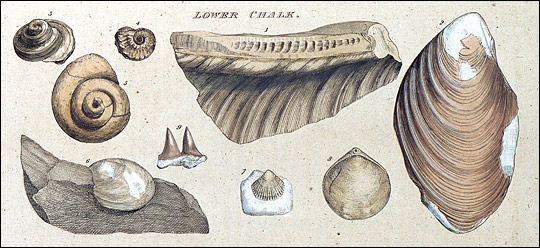

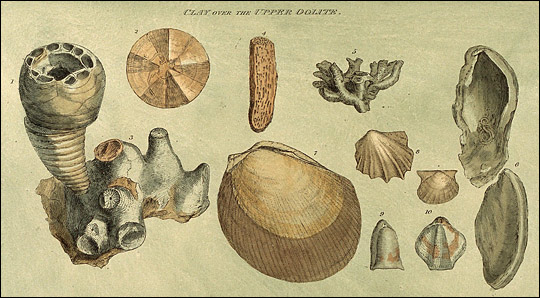

Beginning in 1816, Smith published Strata Identified by Organized Fossils, a guide to identifying English strata based on fossils. The short book contained plates—each colored to approximate the shade of the strata—with illustrations of fossils typically found in many of the layers he mapped. Craig (or Crag, top) is a mixture of sand and shells found in Norfolk and Suffolk counties. Lower Chalk (middle) outcrops on the hills above Bath. Clay over the Upper Oolite (lower) is exposed just south of Bath. (Plates courtesy Cecil J. Schneer, Professor Emeritus, UNH.) | ||

Unlike some early nineteenth-century naturalists, Smith didn’t use fossils to reconstruct past environments or a detailed history of Earth. Yet his principle of fossil succession became the underpinning of much of our understanding about how dramatically Earth’s climate, continents, and life itself have changed over time.

|

William Smith is commemorated along the multi-use Colliers Way, which winds through the same terrain as the Somerset Canal. Jerry Ortmans’ Stone Column features the same types of rocks originally delineated by Smith over 200 years ago (top to bottom): Chalk, Forest Marble (two blocks), Great Oolite, Inferior Oolite, Blue Lias (deeply scored), White Lias (two blocks), and Pennant Stone. (Photograph ©2007 analogueandy.) | ||