| |||

When it comes to coal, perhaps the only thing more controversial than what to do about the heat-trapping carbon dioxide it generates is what to do about the social and environmental costs of getting it out of the ground. Nowhere is the debate over how far we are willing to go for inexpensive energy more contentious than in the coalfields of the Appalachian Mountains, where technology and engineering have allowed the scale of surface coal mines to reach gigantic proportions. |

Mountaintop removal coal mines have changed the shape, altitude, and ecology of large areas of the Appalachian coalfields. This photograph shows part of the Kayford Mountain Mine in West Virginia on October 22, 2006. [© Vivian Stockman, Ohio Valley Environmental Coalition (OVEC).] | ||

| |||

The most controversial mines are known as mountaintop removal mines because coal companies literally remove the tops of mountains with dynamite and earth-moving machines, called draglines, in order to reach coal seams. The waste rock—the remains of the mountains—is piled into neighboring hollows in towering earthen dams called valley fills. The largest fills can approach 800 feet in height and swallow more than a mile of streambed. In southern West Virginia, where the practice is most widespread, some of these behemoth mines are several thousand acres and still growing. |

Coal operators use explosives and enormous machines called draglines to uncover thin, mountaintop coal seams. Draglines, such as this one at the Hobet-21 mine in Boone County, West Virginia, can be more than 20 stories tall, weigh thousands of tons, and operate buckets big enough to hold more than a dozen cars. (Photograph taken on June 11, 2006, © Vivian Stockman, OVEC.) | ||

| |||

The scale of these mines is matched by the social and environmental problems they create. Downstream of mountaintop removal and valley fill sites, water quality and stream life are often degraded. Water, streambed sediments, and fish tissue often harbor concentrations of potentially toxic trace elements, including nickel, lead, cadmium, iron, and selenium, that exceed government standards. The diversity of fish and other aquatic life declines. Hundreds of thousands of acres of some of the world’s most biologically diverse forests outside of the tropics have been lost or degraded, and, to date, efforts to restore them have had limited success. Valley fills have worsened flash flooding during heavy rain events. Blasting has cracked house foundations. Floods from the collapse of valley fills and coal sludge impoundments, though rare, have devastated some watersheds and communities. |

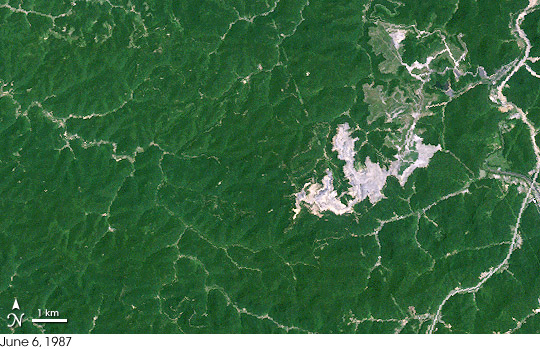

Landsat satellite data collected in 1987 (base image) and 2002 (place mouse over image for comparison) show the growth of the Hobet-21 mountaintop mine in the Mud River watershed of West Virginia. The mine expanded across thousands of acres and produced one of the state’s longest valley fills when rock and dirt were placed into Connelly Branch. The center portion of the mine site had been partially reclaimed with grass (light green) as of 2002. [NASA images by Jesse Allen, based on data provided by the Global Land Cover Facility (GLCF).] | ||

Since the late 1990s, environmental groups and coalfield residents have brought lawsuits against coal operators and regulatory agencies over these mines. Using streams as a landfill for mining waste is illegal under the Clean Water Act, they argue, and the flattened ridge lines and valley fills are a violation of the core requirement of the 1977 Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act: that mining companies restore the land to its original shape—the “approximate original contour”—as best they can. Variances could be granted if the coal operator offered specific plans for post-mining development that would benefit the community, such as schools, housing, or shopping centers, but in most cases, the development never materialized. In West Virginia, the rise in lawsuits created a demand for a state-wide accounting of the impact of mountaintop removal mines, which the agencies responsible for regulating them—the federal Office of Surface Mining, the Army Corps of Engineers, and the West Virginia Department of Environmental Protection—could not initially provide. They couldn’t say conclusively say how many mountaintop removal mines existed, how many streams had been buried by valley fills, how many “approximate original contour” variances had been granted, or whether the promised reclamation and development had actually occurred. |

The leftover rock and dirt from mining is piled into nearby hollows and stream beds in huge earthen dams called valley fills. These terraced fills of waste rock can be hundreds of feet tall. Ponds are built at the foot of the fills to catch sediment-laden runoff. Eventually fills such as this one at the Hobet-21 mine, photographed on July 20, 2007, are seeded with grass to improve erosion control and stability. (©2007 Vivian Stockman, OVEC.) | ||

As part of a settlement of a 1998 lawsuit over a mountaintop removal mine near Blair, West Virginia, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency agreed to conduct an environmental impact study on the cumulative impact of mountaintop removal mining, which it published in 2005. In the roughly 12-million-acre region of eastern Kentucky, southern West Virginia, western Virginia, and eastern Tennessee where mountaintop removal mining takes place, nearly 7 percent of the land had been or would be disturbed by mountaintop removal mines between 1992-2012. More than 1,200 miles of streams had been degraded by mountaintop removal mining. At least 724 miles of streams were completely buried by valley fills between 1985 and 2001. Permits issued since then will affect thousands of additional acres and hundreds of miles of streams. |

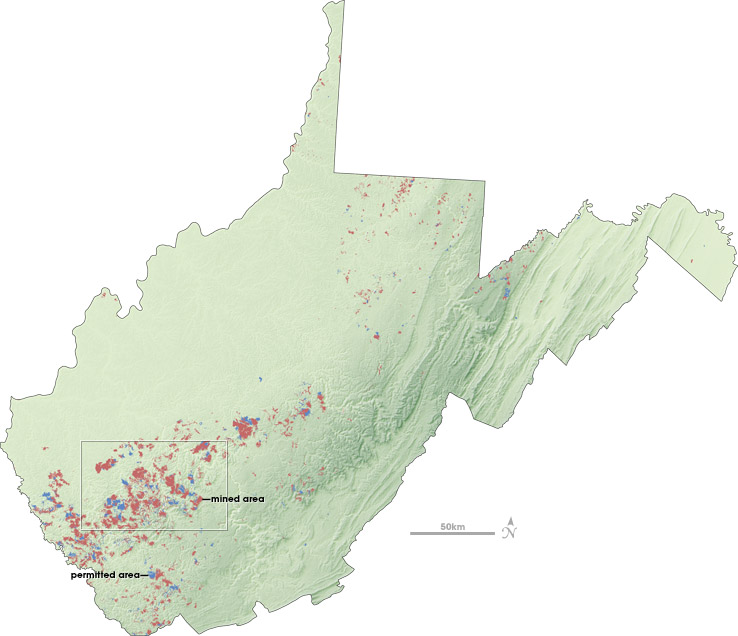

Large areas of West Virginia have been affected by mountaintop removal mining (light red), and additional areas have been permitted but not yet mined (blue). The outlined area contains some of the state’s largest mines, including the Hobet-21 Mine and the Kayford Mine, each of which is more than 10,000 acres. In photo-like satellite imagery (bottom; September 29, 2007), mines create noticeable bald spots in the forested landscape. [NASA map by Robert Simmon and Jesse Allen, based on topographic data from the Shuttle Radar Topography Mapping (SRTM) mission and mine permit data from the W.V. Department of Environmental Protection. NASA image by Jesse Allen, based on data from the MODIS sensor on the Terra satellite.] | ||

| |||

Surface mining at these scales is more economical for coal companies, safer for miners, and, coal operators say, essential for mining the thin seams of lower-sulfur coal more valuable in today’s market. With dynamite and immense machines, surface mines can produce more than two to three times as much coal per miner as underground mines can. Although employment in the coal industry has declined over the past half-century, mining remains the backbone of West Virginia’s economy. Coalfield residents argue bitterly over whether some people’s jobs are more important than other people’s homes or the preservation of the area’s natural heritage. This natural heritage is part of the area’s rural culture, and it draws millions of tourists each year. As courts try to determine how existing environmental statutes apply to mountaintop removal operations, the regulatory framework is shifting. In 2004, the federal Office of Surface Mining announced plans to re-write the “buffer zone” rule that prohibits most mining activities within 100 feet of a stream to make it clear that valley fills in streams were permissible, but subject to regulation. In May 2007, 50 members of the U.S. House of Representatives responded to the proposal by co-sponsoring legislation that would prohibit disposing of mine waste in streams. Meanwhile, citizen lawsuits against coal operators and state and federal regulators continue to work their way through the courts. How these conflicting legislative and judicial issues will be resolved remains uncertain. In the meantime, remote-sensing data and images can be valuable tools for scientists, policymakers, and citizens who are interested in understanding and visualizing the widespread impact of this type of mining on the Appalachian landscape. |

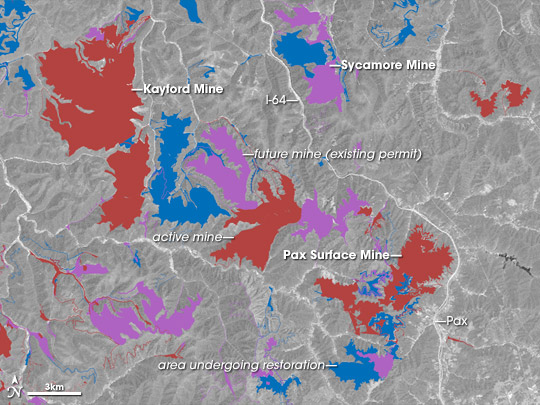

An individual mine permit may only cover a few hundred to a few thousand acres, but mountaintop removal mines often expand over many years through a succession of permits. Combining data on mine permits with satellite imagery (place mouse over image for comparison) helps provide a sense of how the landscape has been or will be altered by mining. This map of the Kayford Mine and others in southwest West Virginia shows active mines (red), areas permitted for future mining (purple), and sites that are being reclaimed (blue). The image shows how the area looked on May 22, 2002. [NASA map and image by Robert Simmon and Jesse Allen, based on Landsat satellite data provided by the Global Land Cover Facility (GLCF) and mine permit data from the W.V. Department of Environmental Protection.] | ||

| |||

|

The rolling, stream-creased mountains of the central and southern Appalachian Mountains are blanketed by forests that have some of the highest biodiversity outside the tropics. Hundreds of thousands of acres of these forests have been lost or degraded by mountaintop removal mining. Not long after this photo of the mountains north of the Mud River in Boone County was taken in July 2005, an expansion of the Hobet-21 mine cleared and leveled large areas in the foreground and middle-ground of the photograph. (Photo ©2005 Vivian Stockman, OVEC.) | ||