| |

To prove that the monsoons shaped the coral reefs, Hatcher and Naseer

would have to demonstrate that a relationship exists between the two

across the entire atoll cluster. Moreover, they would have to compare

the monsoon weather data such as wind speed, rainfall, and wave height

over several decades to detailed maps of the reefs. But when they went

looking for this information, they ran into the same old problem. Though

the climate data were there, detailed maps of the atolls were

non-existent. The only maps of the Maldives were English admiralty

charts from 1896 and modern maps drawn to a scale of one to three

hundred thousand. "They were all maps that were designed for

navigating the waters amongst the islands. We needed maps with enough

detail to see the submerged reef habitats at the scale of about one to

ten thousand," says Hatcher.

|

|

|

| |

The

researchers eventually found a solution to this largely academic

dilemma in a seemingly unlikely place–the Landsat 7 satellite.

Launched in 1999, Landsat 7 orbits approximately from pole to pole

around the Earth. An instrument on board, known as the Enhanced Thematic

Mapper Plus (ETM+), measures the infrared and reflected solar radiation

from the surface of our revolving planet. These readings are beamed as

digital data to receiving stations on the ground where scientists can

convert them into meaningful images of the Earth. With a resolution on

the order of 30 by 30 meters per pixel, the images are not well suited

for viewing details on our planet’s surface any smaller than an

office building. They are, however, extremely useful for mapping and

monitoring large features such as coral atolls.

Traditionally, Landsat 7 has been used to track change in land cover

such as deforestation. At the request of a group of scientists at the

University of South Florida and NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center,

NASA agreed to modify the Landsat 7 image acquisition strategy to begin

monitoring shallow ocean regions. For the past two years the group has

been using these images as part of an effort to map and monitor the

health of coral reefs around the globe. They passed their images of the

Maldives along to Hatcher, who saw them as the perfect means with which

to test their hypothesis. Not only were the images relatively

inexpensive, but they were detailed enough to make out the coral reef

habitat and extensive enough to cover the entire atoll archipelago.

Of course, the satellite images did not come classified and labeled.

The researchers had to take the raw data and demarcate the individual

reefs and any other features in the image that would be helpful in

uncovering the effects of the monsoons on the atoll reefs. More

specifically, they needed to know the dimensions and orientation of each

reef’s growth features, which include the reef crest, the reef

slope, the shallow and deep reef lagoons, the sand flats, and the

vegetated islands.

|

|

Satellite imagery provides the wide-area

images required to map the atolls of the Maldives. By comparing reef

structures throughout the archipelago, scientists can determine what effect

predominant weather patterns have on coral growth. (Image courtesy Abdulla Naseer, Dalhousie University) |

| |

As

most of their work is carried out on a university campus in Nova

Scotia, the researchers had to rely on their expertise regarding coral

reefs, their prior knowledge of the Maldives, and an array of remote

sensing techniques to map each atoll. In some instances, the process was

as easy as outlining an area that looks like a reef or a sand flat. In

other instances, complex computer programs involving fuzzy logic were

used to bring out the various categories. In the end, they found they

could obtain very detailed maps of the Maldives’ reefs from Landsat

7, and the whole endeavor took only a fraction of the time needed to map

the reefs by airplane or boat and cost a great deal less. "Landsat

7’s ability to consistently and rapidly map reefs has given us the

power to test hypotheses with a level of efficiency unheard before in

marine geological research," says Hatcher.

The researchers will employ a Geographic Information System (GIS) to

match their atoll maps point for point with the wind, rain, and wave

height data taken in the Maldives over the last 20 to 30 years. Though

only 20 percent of the reefs have been accounted for so far, the results

seem to confirm the researchers’ hypothesis. The sections of the

atolls facing in the direction of the monsoon winds–east and

west–are wider and slope more gradually into the sea. Those reefs

that were not exposed to the monsoons, either because they face another

direction or because they were shielded by other reef formations, had

more of wedge shape profile with narrow reef crests and steep slopes.

"Though we are in the early stages of the project, the asymmetries

are consistent with the geographic pattern of the monsoons," says

Naseer.

|

|

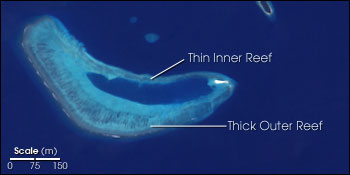

This high-resolution satellite image,

a detaill of the one above, is suggestive of how the monsoons shape the reefs. The wide,

outer edges of the reefs face the monsoon winds, while the thin, inner edge

is protected from them. (Image courtesy Abdulla Naseer, Dalhousie University) |

| |

Since

the atolls do not show obvious signs of erosion, Hatcher says

they likely maintained the same shape throughout the latest rise in sea

level (125 m) that began with the end of the last ice age 12,000 years

ago. Several lines of evidence suggest that the monsoons in that region

of the world have blown with the same strength and direction for many

tens of thousands of years. As these atolls grew above the volcanic

mountain range that forms the backbone of the Maldivian archipelago, the

monsoons acted to continually mold the size and shape of the reefs.

"So in a way both [Darwin’s and Dana’s theories] were

correct for the Maldives," says Hatcher. Though the atolls’

overall shape remains roughly the same for hundreds of feet under the

ocean's surface, they have been continually shaped by the region’s

dominant weather patterns.

Battling a Rising Tide Battling a Rising Tide

Blowing in the Wind Blowing in the Wind

|

|

In the Maldives, monsoon winds drive waves, which stir

up the nutrients needed by the corals. Preliminary research indicates that reefs exposed to

the monsoons grow wider than those that are sheltered. (Photographs courtesy Bruce Hatcher, Dalhousie University) |