A New Career | |||

Growing up in Sydney, on the east coast of Australia, sailing has been a part of Adrienne Cahalan’s life since she was teenager. Even after sailing for over 15 years professionally, it wasn’t until the age of 38 that she returned to school in the United Kingdom for a master’s degree in meteorology. Although trained as a lawyer, her meteorology degree and her racing experience ensured that she would be able to stay at the top of her field as a navigator for international yacht races. In the old days, the navigator’s responsibility was simply to know where a boat was on the ocean and where it was headed. “Nowadays,” says Cahalan, “GPS provides that information for us, so my main focus is to develop a strategy to handle the weather at any given time, to win races by taking the information we receive via satellite and making the adjustments to our course based on the real-time weather. I work with the crew to decide what sails to use for the weather conditions. At the same time I’m also responsible for the maintenance of electronic equipment—computers, cameras, radars, wireless networks—which can be very sensitive to the marine environment.” |

|||

In late 2003 and early 2004, Cahalan was part of a crew who was making preparations for a round-the-world-record attempt when the funding fell through. “I was extremely disappointed,” she says. “So when I got a call in Sydney in February 2004 asking if I could be in England in two days to replace Steve Fossett’s regular navigator on Cheyenne for his attempt at breaking the record, I said ‘Sure, of course.’” American Steve Fossett is an adventurer who has used his own fortune to finance efforts to break records in both sailing and aviation. In 2004, he turned his attention to the round-the-world record. Deciding When to Go“You want to start your trips in winter in the Northern Hemisphere because that means it’s summer in the Southern Hemisphere—and you really don’t want to be sailing in the Southern Ocean off Antarctica in any time other than summer,” explains Cahalan. |

The primary responsibility of a navigator on a modern racing yacht is no longer figuring out where a boat is and which way it is headed—GPS devices keep track of that. Today, a navigator’s primary task is plotting where the boat should go to make the best use of the weather. She is also responsible for maintaining the navigation and communication systems’ complex electronics. (Photograph copyright Nick Leggatt) | ||

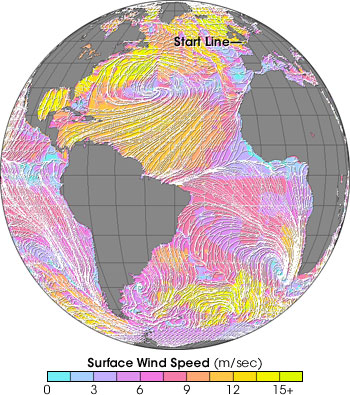

“On the other hand, you don’t want to leave too late into Northern Hemisphere winter,” Cahalan says. “The winter weather in the middle latitudes of the Northern Hemisphere is dominated by low-pressure storm systems that travel from west to east. Once you go around the world and come back through the Atlantic, it is critical to be able to use the northern hemisphere storm track to make good time through the North Atlantic back to England.” If they leave too late in the season, the mid-latitude winter storm pattern may have fizzled out by the time they return. Being ready to go at a moment’s notice is a pre-requisite for setting out for a trip like the one they were about to undertake. “Timing the launch date is one of the most crucial decisions on the whole trip,” explains Cahalan. “The record at the time was 64 days, and to beat that, we knew we had to reach the equator in under 8 days. We were looking for a forecast that would get us there in that window.” The window would have to include a northerly wind to push them southward away from England and into the trade winds (a belt of predominantly easterly winds in both hemispheres that blow from about 30 degrees latitude toward the equator). “We were leaving from a town called Plymouth, on the southwest coast of England, about 100 nautical miles from the race start line in the English Channel. It was already the beginning of February, and we starting to worry about getting to the Southern Ocean too late and returning to the Northern Hemisphere when the westerly storm track was gone.” |

Choosing a start date is one of the trickiest parts of round-the-world sailing races. Even in late summer (in the Southern Hemisphere), cold weather, rough seas, and icebergs make the Southern Ocean, pictured at left, a dangerous place to sail. Because of these dangers, most trips begin in middle to late winter in the Northern Hemisphere. (Photographs copyright Nick Leggatt) | ||

Cahalan pored over weather reports and briefings from Commander’s Weather, the New Hampshire-based company that the team had hired to provide forecasting support for their voyage. Finally, she says, “We saw a window of good trade winds, and we made a late decision on Friday afternoon to leave for the start line. The weather models predicted this was the last opportunity for several weeks. The problem was that getting to the start line was going to be rough—50 knot winds getting there.” If you aren’t a sailor, you could be excused for thinking that a fifty-knot tailwind sounds like a great stroke of luck. But in a catamaran-type boat like Cheyenne, says Cahalan, “You really want winds of 35 knots maximum.” Anything higher than that and the boat, including the mast and sails, come under a lot of strain, mostly because of the waves that develop. She adds, “Above those speeds, the sailing is very rough, very bumpy.” On Friday, February 6, Cahalan came aboard with the rest of the crew—the only woman among 12 men. When it came time to leave, the weather was cold and blowing. Cahalan admits saying to herself, “Ohh, I don’t want to go. What am I thinking?” But within a day, they were in the Bay of Biscay west of France. “It was beautiful and sunny.” |

Cheyenne departed on her round-the-world journey on February 7, 2004. The crew decided to brave high winds (over 50 knots) on the way to the start in order to catch favorable trade winds in the mid-Atlantic. This image, made from QuikSCAT satellite data, shows wind direction (arrows) and speed (color) at 12:00 GMT on February 7, 2004. Blue represents calm winds, pink moderate winds, and yellow high winds. (Image courtesy NASA/JPL Seaflux) | ||