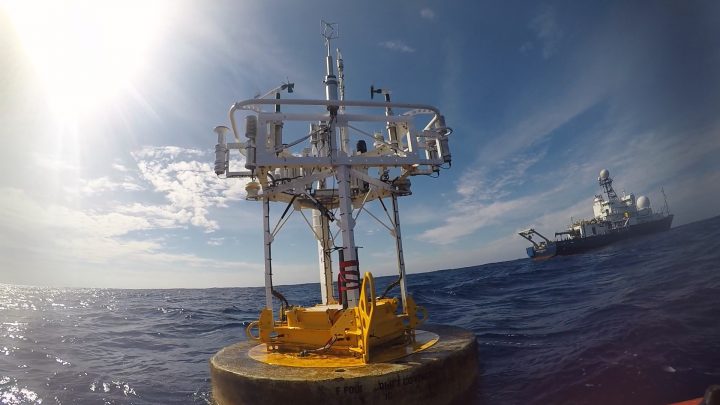

WHOI Mooring Buoy (credit Ray Graham).

One of the reasons our work requires a large research vessel is that we are dealing with large arrays of sensors moored in the deep ocean. That requires big buoys, lots of rope and wire, lots of floatation, and big anchors with very strong and steady human guidance.

Time series collected from moorings are among the most valuable data sets collected in oceanography. Anchoring sensors at one location and precisely placing them at pre-determined depths provides a view of the ocean that cannot be supplied by any other means.

SPURS-2 deployed three moorings in late summer of 2016 and recover the equipment now, in November 2017. Our “central mooring” from Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution is heavily instrumented with temperature, salinity, and velocity sensors (See Prior Blogs: Mooring Deployments and Mooring Deployment). Two additional moorings from NOAA PMEL (See Prior Blog: NOAA Contributions to SPURS) are instrumented with “Prawlers” (See prior blog: Prawlers, Engineers, and the Future of Oceanography at Sea) – a single sensor package that crawls up and down the mooring wire profiling the water column. In addition to ocean measurements, these moorings provide a year long record of the surface meteorological conditions.

Silky Shark on the line at WHOI mooring.

One of the interesting thing about these moorings, that you seldom hear about, is the “buoy ride.” Several times during this voyage we have put men on the mooring buoy to complete assignments such as replace batteries, change out meteorological gear, and finally to remove all the meteorological equipment in preparation for recovery of the entire mooring. Ben Pietro and Ray Graham described the experience quite vividly – of clambering aboard the buoy from Revelle’s small boat and attempting to stay safe on a rocking, rolling, heaving, slippery, guano-encrusted, shark-surrounded, pillar of modern oceanography.

In the approach via small boat, we are told, one is impressed immediately by the number and variety of fish swimming around the buoy. There are also the menacing, shadowy figures of sharks among the fast-swimming tuna and mahimahi. That gives the short leap from the boat to the buoy the feeling of a do-or-die effort!

Once aboard the buoy the footing is slippery with seawater and guano, so the discipline of a rock climber is required. It may be only a short way down, but who wants to splash around with hungry sharks? One only has to recall the fishing, of days recently past, where on one cast all that was brought aboard was the lure and the head of the tuna; the sharks having won an easy and quick dinner. Best to hold on tight. Ben said his knees were sore from clamping down hard on the buoy while using both hands to get the meteorological gear free and stowed.

Serious profession this!

Ray and Ben riding the WHOI Buoy!

One of the fascinating projects to watch during the mooring recovery is the dismantling of the “hardhats” – the mass of floatation at the bottom of the mooring above the anchor that brings the bottom end to the surface. As deployed, it is a tall tidy assembly of glass balls in their protective hardhats, in bunches of four, connected with chains. As recovered (see photo), it is a confusing puzzle of twisted chain and shackles in an untidy pile. Amazingly, it took a dozen people only twenty minutes to untangle the puzzle and stow the hardhats four by four back in their shipping box (AKA, the snake pit). Honestly, it was an amazing operation to watch!

The Puzzle of Untangling the Hardhats.

While ocean moorings are often described as autonomous observing platforms, the human ingenuity required to deploy and recover them demands a steady human with a tight grip.

By Eric Lindstrom

Plastic bottle floating by the ship.

A 1960’s movie classic, “The Graduate” (1967), contains a scene where the young Benjamin Braddock (Dustin Hoffman) is given advice about his future by the worldly Mr. McGuire (Walter Brooke):

Mr. McGuire: I want to say one word to you. Just one word.

Benjamin: Yes, sir.

Mr. McGuire: Are you listening?

Benjamin: Yes, I am.

Mr. McGuire: Plastics.

A report from the World Economic Forum earlier this year estimates that the weight of plastic in the ocean will equal the weigh of fish by 2050. According to the report the worldwide use of plastic has increased 20-fold in the past 50 years and is expected to double again in the next 20 years.

Ocean pollution by plastic has been worrisome for years, but the global prevalence of plastic in the ocean and the full impact of its consequences are more recently appreciated. Plastic breaks down at sea into “microplastics” that are now part of the floating plankton – the base of the food web in the ocean. So, plastic is increasingly found in the stomachs of marine organisms. Recent estimates put the amount of plastic floating in the world’s oceans at more than 5.25 trillion pieces weighing more than 268,000 metric tons. That translates to as much as 100,000 pieces per square kilometer in some areas of the ocean. This is a new ocean habitat know as the plastisphere.

The plastisphere is a new waterfront mobile home for marine microorganisms. It potentially provides a floating home for microbes to take long tours of the ocean that were heretofore impossible. The ecological implications of this new globalization of the ocean microbial biota have yet to be determined.

Zooplankton and fish consume microplastics as they forage the plankton. Scientists think that nearly every bird that feeds at sea has a burden from the plastisphere as they forage the small fish. Given the rapidly increasing tonnage of plastic joining the plastisphere and the plastisphere invasion of the marine food chain, we too will be doing battle with the plastisphere, if not already.

Marine debris is not all plastic and has many sources. However, dumping from ships at sea is NOT the major source. Dumping at sea has been highly regulated for more than 30 years. The major source of plastics and other debris in the ocean is from land sources and river runoff.

Dan Clark with two of his nearly 50 bottles of samples for investigation of ocean microplastics.

In SPURS-2 we are very far from land – 7.5 days transit by ship from the Hawaiian Islands. Yet, still, we spy plastic bottles, shoes, fishing gear, and other unidentifiable debris at the surface of the ocean every day. We also have evidence that microplastics exist here. A UV filter, part of the water intake to one of R/V Revelle’s new thermosalinograph systems (Underway Salinity Profiling System) inadvertently acts as a microplastics sampler. Floating plastics, fibers and ocean detritus accumulate in the UV filter chamber that used to sterilize the saltwater sample prior to salinity sensing. The debris in the filter must be cleaned frequently to keep the system in working order and prevent bioaccumulation in salinity sensor. This thermosalinograph system was not designed for studying ocean debris, but it is a plenty worrisome observation. Dan Clark from University of Washington’s Applied Physics Laboratory is keeping the daily samples for analysis after SPURS-2. This a nice example of citizen science undertaken through the curiosity and personal initiative of Dan over and above his many other duties. Now he just has to figure out how to deal with the unusual sampling protocol!

The ocean is actually quite forgiving as a disposal site for human detritus in moderation, except plastic. Organics can be recycled by marine life, wood is disposed of quickly by boring worms, metals can be corroded by seawater, but plastic cannot be dissolved or digested. It is only humans who create and produce plastic goods. It is only humans who can dispose of plastic properly. Plastic MUST be recycled or disposed in landfills. Plastic has no business being in the ocean. We can only hope that the plastisphere we have created can be tamed and that it does not spawn deadly new microbes by virtue of its existence.

So, next time you are using a plastic good, make sure its afterlife is not in the plastisphere of the ocean. Benjamin’s retort to Mr. McGuire should have been “Yes. Mr. McGuire. Plastics are the future. If we can find proper ways to dispose of them!”

By Eric Lindstrom

Monkey makes its own mess!

Long ago on a planet very similar to our own, oceanography was done without the Internet or regular communication with shore. It required careful planning and forecasts of the conditions to be encountered were vague at best. Executing the original plan of work for a voyage was always a good objective.

Unlike those days on that planet, the shipboard work of SPURS-2 seeks to optimize our operation as we go by depending on a “dry team” ashore for a daily flow of information. The information comes from a number of sources including satellites, in situ data (data collected in place), models, and combinations of these sources. The daily flow of information comes to us via the Internet in a “tarball.” In computing, tar is a computer software utility (originating from Tape ARchive) for collecting many files into one archive file, often referred to as a tarball. Scientists on R/V Revelle receive the daily tarball assembled by our dry team at the NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory (in association with many SPURS-2 scientists ashore). The tarball contains files for daily weather and oceanographic analysis and a wealth of ancillary information. The tarball is information desired by the team aboard the ship, a key point that should not be overlooked in the following discourse.

SPURS-2 planning is a daily occurrence in the R/V Revelle library. From left to right: Janet Spintall, Denis Volkov, Kyla Drushka, Ben Hodges, Audry Hasson, Julian Schanze and Jim Edson.

Well, you can see where I am going with this: a tarball is also a blob of petroleum that has been weathered after floating in the ocean, sticky marine debris from the age of oil spills. With all due respect to the efforts of the dry team, commonality of the computing and oil tarball terminology becomes all too clear when one tries to reconcile the complex flows of data from both the tarball and the vast array of instruments on the ship. The tangle of seemingly conflicting information can make you feel like you are dealing with a tarball of the sticky black variety!

The tarball does focus our attention by feeding back to us our own observations. After R/V Revelle has deployed moorings, drifters, and floats we might receive back meteorological data from the central WHOI mooring, profiles from the NOAA moorings, trajectories of surface drifters, and profiles from the Argo floats. This real information may or may not conflict with what we imagined we would see (and built our plans around). So, this tarball pushes us into consideration of whether our plans going forward need revision or remain sound.

For example, the tarball is always an implicit invitation to re-consider the planned work to take account of current or forecast conditions. Ostensibly this information enables us to make the most of our valuable ship time. However, having a constantly evolving plan of action is rough on people and their routines. Plans tend to lose their certainty.

Of course, proposals are funded and years of work are banking on our executing a planned set of measurements. However, the decisions are difficult, if we planned to collect seven days of Surface Salinity Profiler data in rainy conditions and our planned operations turn out to be south of the actual rains for the previous two weeks, do we change our plans? Or, will Mother Nature bring rain to us in the coming weeks if we simply execute the plan with which we came to sea? The tarball gives us some weather projections, satellite rain rate and cloud maps, as well as current and salinity patterns in the ocean and model forecasts to help with the decision-making. Unfortunately what seems clear and useful to those at desks thousands of miles away, can be less than clear and ultimately confusing when working on an isolated patch of ocean far from regular observation. The effort to make good use and sense of the tarball is one of the additional challenges facing modern oceanography.

Two-panel plots of satellite salinity from the SMOS and SMAP missions. The only difference is the color scale; it is kind of a Rorschach test for oceanographers. Do you see fronts in one and not the other? Well, they are the same! What you see and interpret can be biased by how you present the information. That is another sticky mess in the tarball.

Before the tarball, seagoing oceangraphy was simpler (and more dangerous) and plans were simply to be executed. With the tarball, science is safer and more nimble and plans are malleable. I think that for us, older humans, the modern way with the tarball is more stressful. Or maybe, if you came of age with the Internet, life without the tarball is unimaginably silly and stupid. For a young oceanographer the science IS the sticky mess inside the tarball!

Whatever the reality, our information age has made a day at sea a challenge in environmental analysis. No more hoping, imagining, or guessing – it is all in the tarball if only you can figure it out!

By Eric Lindstrom

Food service on the R/V Revelle.

Food aboard the R/V Revelle is a cornerstone of happiness and good morale. Jay Erickson and Richard Buck are the cooks during this voyage and have many years of experience working together on R/V Revelle. I followed their daily routine all day on Friday, September 2, so that I can give you some beyond-consumer incite about food on the R/V Revelle. I will stipulate that their work is very good indeed and that we have been getting well fed. Since scales don’t work at sea, no weight gain can be observed. So says the fat blogger.

Jay Erickson, Chief Cook on the R/V Revelle.

Richard Buck, Cook, R/V Revelle.

I think it is best to describe this important aspect of life on R/V Revelle in two ways. First is the routine that makes food service run like clockwork every day. Second are the secrets or magic of shipboard food service that those on land might find curious or amazing. I can touch on only a few highlights.

I’ll start with the clockwork routine. Richard and Jay alternate work assignments. Each day one them does the hot food preparation and other has salad/cold food preparation, cleaning/dishwashing, and supply runs to the stores (three decks down). The next day they switch. The key menu options for hot food are generally decided on the prior evening. Only one day has a predictable menu – Sunday is steak day! Jay and Richard’s workdays are over 12 hours long with two short breaks. That is a heavy, relentless duty.

Breakfast preparation starts at 6:00 am. Breakfast food options are those of a typical American diner (e.g., eggs several ways, several meats, potato, pancakes, oatmeal, cereal, fresh fruit), without the short orders, and do not vary substantially from day to day. Most people do not vary in their breakfast food choices so I’d characterize it as the constant, dependable meal (least challenging for the cooks).

Salad bar at every meal.

Hot meal of Balboa chicken and shrimp noodle soup.

After a short break from about 8:30 to 9:00 am, lunch preparation begins with galley and dining room cleaning. Typical lunch and dinner menus include a featured main course, a couple of side dishes, a vegetarian option, and a soup. After lunch cleanup there is another break in the action from around 1:30 to 2:30 pm. Some preparation for dinner will have been started during the lunch service.

Birthday cake for Andrew and Peter.

Dinner preparation includes renewal and refreshment of the salad bar, bread baking, and work on the main meal from soup to nuts, as they say. Every day there are some extras or special events as well. On my day in the kitchen there were two birthdays, so a decorated birthday cake was prepared over the course of the day. Likewise, fresh bread, cookies, or a special dessert might be created for the dinner service.

As I learned over the course of the day, the vast share of labor goes into food preparation and cleanliness. The R/V Revelle professional facilities allow for the rapid and efficient cooking of food for 50-60 people. However, the washing and chopping of large quantities of fruit and vegetables, and meat handling are labor intensive. So too are the good habits of kitchen hygiene that assure that everything is done right and sparkling clean at all times. As you might expect, the work is hard enough without everything being shipshape and well organized. Fastidiousness was a hallmark of Jay and Richard’s work.

There are many challenges to creation of good meals at sea. Obviously motion of the ship can be a big issue. A ship’s cook is a cook who has mastered the art of corralling sloshing food! Richard told me of attempts to bake a level cake in the seas of the Southern Ocean. Rather than having it baked into the leaning cake of Pisa, he tried to balance the sea motion by turning the cake in the oven every few minutes to counter the sloshing of the batter. In that case, the ocean won…but I think the birthday recipient appreciated the effort nonetheless.

Fresh bread just out of the oven.

Jay shared an interesting secret of leftovers. Oatmeal is available for breakfast every day. Leftover oatmeal is mixed with water and yeast after breakfast and the slurry left to ferment. It is transformed by this effort of the microbes and a resourceful cook into the delicious bread at dinner!

Let us admire a three-week-old lettuce, looking like it was fresh.

A great deal of science and experience goes into the food storage on a ship. Three weeks at sea and we still have lettuce and perfect avocados. That never happens for me at home! While each fruit and vegetable seems to have its own story with regard to ripeness at purchase, storage, and revitalization, the keys to longevity seem to be in the cold room temperature and humidity plus the skills of Jay and Richard to give foods a second chance. Lettuce, for example, might look finished due to a dehydrating stay in the cold storage, but skilled knife work, a cold bath, and a little secret chemistry can return lettuce to salad fitness!

We are all in debt to the skill and labor of Richard and Jay. We will feel the full extent of the deliciousness they loaned to us when we climb on the scale back home!

By Eric Lindstrom

A longstanding technical challenge for oceanography has been how to measure the sea surface – temperature, salinity, gas exchange, or surfactants – to name a few examples. Obviously enough, the surface is where the ocean and atmosphere interact and exchange heat, freshwater, gases, momentum, and particles of all kinds. So, how do we measure the properties and exchanges right at the surface? If we are on a ship or any floating platform, the platform disturbs the surface. From satellites we can measure many properties of the surface but only on very broad scales. The R/V Revelle, right now, is the ship showing how modern science is meeting the challenge. Let me tell you about some key elements.

Julian Schanze from Earth and Space Research in Seattle and Jim Edson from University of Connecticut have brought two instruments aboard with innovative ways to measure the temperature and salinity at the surface – the Sea Snake for temperature (Edson) and the Surface Salinity Snake (Shanze) for, obviously, surface salinity. The former places a temperature sensor at the end of flexible hose that is hung outboard from the bow of the ship (near the wake), to continuously measure temperature. The Salinity Snake, outboard of the wake passes water through a vortex de-bubbler and thermosalinograph to obtain an estimate of salinity within inches of the ocean surface. It is an awesome “contraption” (with no offense to Julian).

The Salinity Snake being deployed over the starboard side.

Julian Schanze’s birthday balloon.

Today is Julian’s birthday so all the Salinity Snake gear has been draped with colorful paper snakes carrying birthday greetings. Julian participated in SPURS-1 in 2012 and has since received his PhD and is making a name for himself by tackling surface salinity science from gadget to satellite and from seawater intake to space. It is wonderful to have someone so capable on the NASA Ocean Salinity Science Team!

Andy Jessup, our chief scientist from University of Washington Applied Physics Laboratory and Michael Reynolds from Remote Measurements and Research Co. in Seattle have brought a dazzling array of instruments for measuring and probing the skin temperature of the ocean. The surface of the ocean is known to have a cool skin at the molecular level. Photos of the sea surface with infrared cameras reveal complex and interesting patterns as a result of mixing, wave breaking, surfactant conditions, and wind. NASA has always had a deep interest in skin temperature because satellites do measure this skin temperature while every probe you stick in the ocean measures something deeper and different than skin temperature. From the Revelle, Andy and Michael are using several infrared radiometers and cameras to measure and depict the sea surface skin temperature. There is one on a boom to measure outboard of the ship wake, one mounted on the rail to look outward from the ship and another on a balloon to take infrared photos of the skin from 300 feet above the ship (the Lighter-Than-Air InfraRed System – LTAIRS.)

The laboratory end of the Salinity Snake and Carbon Dioxide analysis.

LTAIRS ascends toward 300 feet.

Eric Chan, from University of Hawaii, is aboard measuring making a suite of carbon dioxide, pH, and Dissolved Inorganic Carbon measurements for principal investigator David Ho. They study the exchange of carbon dioxide across the air-sea interface and they’re particularly interested in how rainwater on the surface of the ocean impacts the gas exchanges.

The array of instrumentation aboard Revelle is quite astonishing and the technical innovations displayed in measuring the sea surface are truly remarkable. And I haven’t even mentioned the Surface Salinity Profiler yet in this blog post. I have been teasing you with that since the start of the voyage and I PROMISE to give it a blog entry all to itself!

Today is also the birthday of the R/V Revelle Captain, Christopher Curl. I am sure I speak on behalf of the entire SPURS-2 science party when I offer him a hearty “HAPPY BIRTHDAY!” and say how pleased we are with the entire ship and crew of R/V Revelle. I guess that sharing the ship with a group of rare ocean-skin specialists with sea snakes is not how he imagined this birthday, but he is quick with a smile and will roll with our skinny offerings!