May 25, 2024

Some 25 of us were up before 6 a.m. to head out on the bus from the hotel to Burlington International Airport to catch the C-130 aircraft, a military transport plane repurposed for NASA fieldwork, to begin our 7-hour flight to Pituffik.

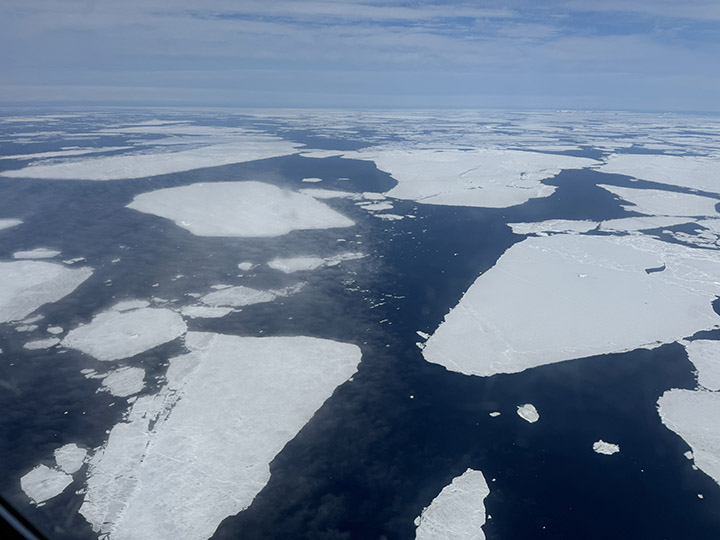

Several mountains of baggage, including scientific instruments and personal luggage, separate us from the less-well-heated economy cabin, which was probably reserved for graduate students, though we are far too collegial a group to check seat assignments. As we head north and east, the landscape out the window is vast, entirely gray-scale, and unforgiving: sea ice with streaks and patches of open water as far as one can see in every direction.

About halfway through the flight, we cross the Arctic Circle. Here the scene is often reduced to pure gray, and one cannot tell what is sea ice, snow, or cloud. This is the challenge we have long faced when attempting to interpret our remote sensing imagery; now, as an early gift of the expedition, I experience it directly.

May 26, 2024

The site is halfway between Washington and Moscow. Most or all of the buildings were prefabricated, brought here by ship in the summer, and mounted on stilts due to the permafrost. Some rough grasses are the only apparent vegetation.

In some ways, the base is well appointed. There is a sports center with an abundance of every conceivable exercise machine, also a tanning machine and a perpetual pool, a huge gym, and a yoga room. There is a recreation center with a movie theater, a lounge area with free apples, tea, and coffee, a game room that is more like an arcade with multiple video machines, and a craft center that has sewing machines (including a state-of-the-art Serger), rock cutting and polishing machines, computer graphics, and printers.

This is a remote place. The site is protected by a thousand kilometers of ice in nearly all directions, and the only ways to get here are by air or by boat for a couple of months of the year, when the sea is not frozen. With full daylight all day and “night,” the times-of-day are marked only by artificial clocks; the natural ones are essentially absent.

May 27, 2024

This was mostly a flight-planning day, getting ready for the first science flight of the campaign. It turned cold, windy, and snow fell today. This was more like what I expected but didn’t experience during the first two days. But now it is sunny again, around 6 p.m., and near-freezing, so there is still standing water on the roadways, and we are past the season when it is safe to walk on the ice-bound bay. The severe environment calls for some specific adaptations.

For example, the outer doors have latches that seal upward, so a bear pushing down on the handle will be unable to open the door. The walkways are made of open steel grids, so snow and mud will drip through. Boots are to be brushed before entering buildings, and plastic boot covers are provided in an effort to limit the amount of dirt that is tracked in.

I took a late-night walk. It’s daylight anyway, though overcast, windy, cold, and flurrying. Pretty much what I expected here.

The power went out twice today. Everything goes down, including the internet. I’m trying to keep everything charged, in case it happens again. Today’s weather represents “Condition Alpha” for storm warnings. That means just be on alert, in case things change. Condition Bravo means you cannot go outdoors without a buddy, or drive alone without a radio. Condition Charlie means you can’t walk out at all; there is a base taxi for urgent movement. Condition Delta: shelter in place.

The pipes are all above-ground because of the freeze-thaw cycle that would destroy the pipes. I guess they must be heated and insulated. They cross the road by going overhead.

Car and truck engines must be heated to avoid freezing and cracking. So, many of the buildings have power cords hanging out in front to run electric engine-block heaters. I didn’t take the last picture quite at midnight, but the scene doesn’t change much during the night.

I think I mentioned that it is mud season here. This is no joke. The place has a very industrial feel, and the only place to walk is on the mud roads. I’ve heard it will get worse as the mud deepens, and mosquitoes come out. Something to look forward to…

May 28, 2024

We had our first flight with the P3 today, and it was far better than I had expected. There was a rare case of cloud-free atmosphere over sea ice in one area north of Greenland where some buoys had been deployed, which allowed for both surface ice and aerosol characterization. Also, a nearly 3-hour run at ~500 feet captured aerosol properties over open water along the northern part of Baffin Bay. Among our objectives are learning the sources and properties of aerosols in the Arctic, their evolution as they age, and their impact on clouds. Others are especially interested in the properties of sea ice as it melts. So, this gives us a start on those objectives.

May 29, 2024

The wind is a force of nature. Today it has been blowing at something like 40 miles per hour, with gusts considerably higher. It literally takes your breath away—and this is just Condition Alpha.

Gusts create the sensation of blowing you away. All this under a relatively clear sky, bright sun, just a few clouds. It is somewhat other-worldly to one who has lived a life at lower latitudes. The temperature is only a few degrees below freezing, but the weather today gives new meaning to the term “wind chill.”

June 1, 2024

Today was an official day off, and in particular, a mental health day for the forecasters. Several of the military folks on the base arranged to take a group of us on a hike over the Greenland Ice Cap. There were 15 of us in five trucks. The trip involved a fair amount of driving on gravel roads in trucks—about half the time driving, half hiking – 5 hours total. The hike itself was about 5 or 6 miles, and we walked around and then on the glacier, though we never did find the Starbucks.

In addition to the stark beauty of the rock fields and ice, the sky is unlike anything we normally see at lower latitudes. The surface is cold, and the atmosphere is no colder (and sometimes is even warmer) than the surface, i.e., it is stably stratified—the “warm” air is already up, so there is not a lot of warm air rising and mixing that typically happens when the surface is heated directly by the Sun.

The glaciers have brought an enormous diversity of stones that litter the ground, and every piece of wood here was carried in from somewhere else. There are little clumps of vegetation, just enough to satisfy the appetites of musk oxen.

So far, I’ve seen Arctic fox (no pictures—they disappeared too quickly), musk ox in the distance, Arctic hare, and snow goose. No polar bears—and no complaints about that.

June 7, 2024

This evening I took a long walk out to the ice-bound pier… AND I SAW AN OTTER!!!

June 4, 2024

The Arctic foxes are molting. They were very cute when their coats were all white. Now they are losing their winter coats and turning brown. I did see a couple of full white coats, but was too slow to get a photo.

June 8, 2024

The project rented a van, and ten of us went off to climb the Dundas, that imposing rock feature not far from the base, though to get there without walking on thin ice (here the term is not merely a metaphor), one has to drive about 30 minutes over rocky and sometimes quite steep roads around the frozen bay.

The angle of repose is the angle a pile of dry sand (or salt) will make if you dump a bucket of it on the ground. It is generally steep (depends in part on the grain size and shape of the sand particles). Dundas is about 725 feet high; it appears to be the remnant of a glacial moraine—rock pushed here by an advancing ice sheet at least that high, that remained after the ice melted away. It is loose sand and rock, mostly gravel and cobble-sized. The climb up was, frankly, arduous, as there are not a lot of footholds.

The first part was steep enough that going on all fours was necessary in places, and the sand and small rocks would slip easily down the slope as one persevered upward. The final part was up a sheer rock wall that was graced, mercifully, with a sturdy rope. My pictures are lacking for the entire traverse, as all my effort went into the climb itself. I did stop part way up the rock wall to check my life insurance policy.

The view from the top was spectacular, but truthfully, there are so many great vistas in this rugged place that the main reward was accomplishing the ascent itself.

The way down was similarly fraught, except that below the rock wall, I had pretty much no choice but to slide down bit by bit—the loose surface material would give way at every step. So, on my back, lift up my rear, slide a few feet using my boots to stop, and repeat. There was some interesting vegetation on the slope—tiny plants and lichen, which I did photograph. I’m told that some of these plants can be hundreds of years old.

In the distance, we saw some dark spots that the binoculars suggested were seals. (Oh, yes—someone here said that my otter from last night was actually a ring seal; not sure that is authoritative, but…).

June 9, 2024

I agreed to join this afternoon’s walk up the edge of the Greenland Ice Sheet.

The slope is moderate by Dundas standards, and the path is completely snow-covered. The walk up is of course uphill, and a steady wind of 30–40 mph (the katabatic wind), with significantly higher gusts, blows off the ice. This guaranteed that however far we got up the ice sheet, we would certainly be able to make it down, either on foot or airborne.

There were pools of water within ice basins at the base. They look a beautiful shade of blue. We saw this in Alaska as well. I think it must be that ice either absorbs all the longer wavelengths, or it preferentially scatters blue, or both. The optics here are stunning, at least to me. Probably because they are unfamiliar.

One way painters provide a sense of distance in a painting is with “atmospherics,” that is, they increasingly blur the edges of more distant objects to account for light scattering by atmospheric gas and aerosols. Mountain climbers experience the opposite, in the thinner atmosphere, remote objects are sharper than they would in everyday experience, so more distant objects appear closer than they actually are. This is true here in Greenland as well, though we are not at a very high elevation along the coast. I expect the phenomenon in this case is due to a very clean atmosphere.

June 11, 2024

Today I got to fly on the P-3. Every satellite scientist should be required to take at least one such flight to see what the Earth is really like. We flew across northern Greenland and over sea ice. In the two weeks since the campaign deployment began, the depth of the sea ice, and the snow upon it, both decreased at those buoys (where it was measured), and, of course, most everywhere else as well.

A field campaign is a layered operation. Aircraft flight scientists build, run, and maintain the twenty or so instruments that measure particle composition, gas concentration, cloud properties, surface reflectivity, and upwelling and downwelling energy. They are awake by 4 a.m. to prepare their instruments for flight, worry about power supplies and calibration, then sit on the plane for six or seven hours, noting what they see from their measurements and out the window.

The number of leads (i.e., openings in the ice) has increased in places. We flew at high elevation to survey the area, measure the overall surface topography and reflectance, and sample aerosol layers aloft, then descended to 300 feet above the ice to capture aerosols emanating from the surface. The photos tell an accessible part of the story. The rest must be teased out of the data in the coming months and years. But my ride is over for now—there is an aerosol forecast due tomorrow.

June 12, 2024

It was flurrying this evening, and my walk carried me down toward the pier. But you might be pleased to know, I did not go all the way; several seals have now been seen on the ice at the pier. My otter or seal in the water was the first anyone saw, and although they say it is relatively rare for bears to go near the base, seals are their primary food. I figured, after a long winter hibernation, a bear might not count me as even a light snack, but in consideration that I had already booked my flight home, I turned around before getting very near the water’s edge.

June 14, 2024

I should say that the food here is okay. Better than I expected. Of course, in such circumstances, it pays to begin with low expectations: hardtack, pemmican, and beef jerky. The cafeteria serves a lot of beef and pork, but there is also chicken, a reasonable salad bar, excellent, fresh bread (the highlight in my opinion), always two of THE three kinds of fruit (apples, oranges, and bananas—so yes, they mix apples and oranges), and of course, Danish, at least in the morning.

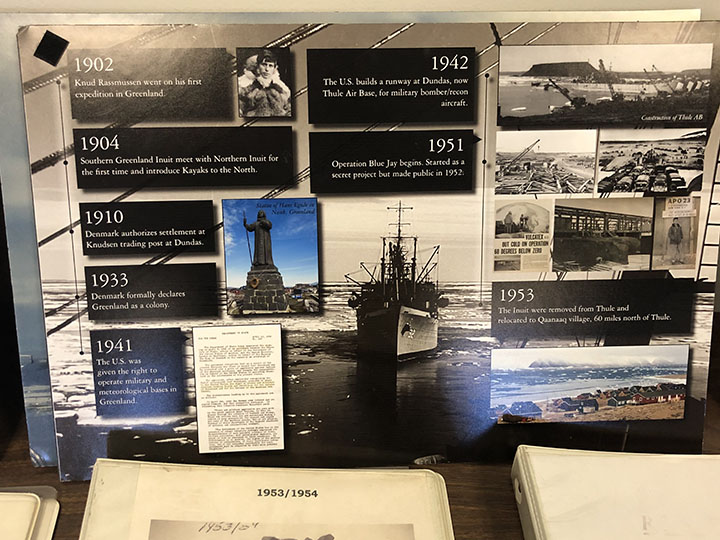

In the evening I took a walk, as usual, and ended up in one of the dozens of prefab buildings on the base, with the suggestive label “Heritage Hall.” The door was not locked, and the lights turned on as you entered each room. The place is a sort of museum, a repository for things discarded from the 1950s and 60s.

They have a computer punch-card machine, a vacuum-tube TV set, and a radar scope you will recognize from science-fiction movies. Also some notebooks with photos of the army’s Camp Tuto (now abandoned—only remnants of the airfield remain) and the presumptive city “Camp Century” they built into the ice in the 1950s. The walls flowed at glacial speed but ultimately collapsed.

Thule base was established in 1951, succeeding three waves of Inuit who inhabited the area, apparently beginning 4,500 years ago. The most recent came around 900 CE, met the Norse about 100 years later, and were moved to a new village 60 miles to the north in 1953. There is even a Life Magazine cover showing ships delivering material to the base in September 1952.

Ralph Kahn, an emeritus research scientist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center now at the Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics at the University of Colorado Boulder, spent three weeks at Pituffik Space Base in northern Greenland in the summer of 2024. He was one of dozens of scientists who participated in ARCSIX (Arctic Radiation-Cloud Aerosol-Surface Interaction Experiment), a NASA-sponsored field campaign that made detailed observations of clouds and atmospheric particles to better understand the processes that affect the seasonal melting of Arctic sea ice. These excerpts from his emails home to family provide a glimpse of what life was like on one of the world’s most northern scientific outposts in the world. Photos were taken by Kahn or Gary Banzinger, a NASA videographer who also participated in the campaign. Kahn, an atmospheric scientist, worked with colleagues to provide daily aerosol forecasts that were used to help plan flights.

“PACE is a mission that will use the unique vantage point of space to study some of the smallest things that can have the biggest impact.” — Karen St. Germain, director of NASA’s Earth Science Division

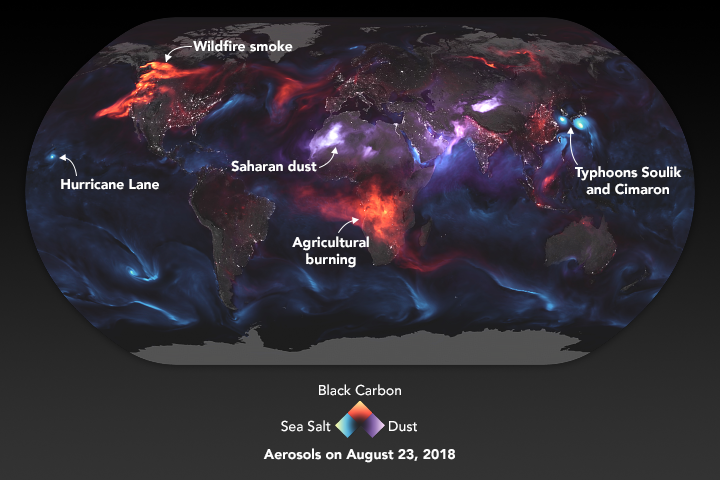

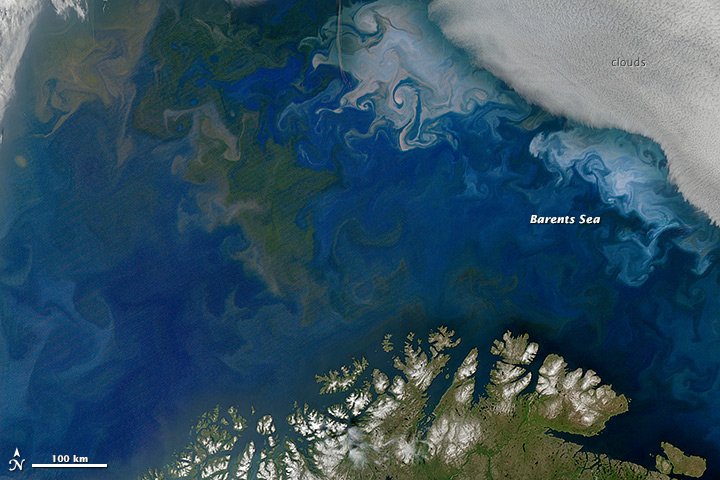

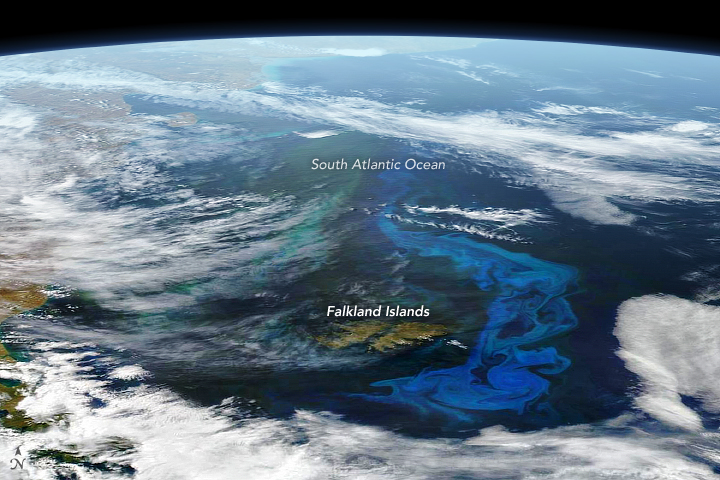

The skies above us are teeming with tiny particles of dust, sea salt, smoke, and human-made pollutants. The seas, oceans, and lakes around us are teeming with microscopic, plant-like organisms. In both cases, individual bits of these tiny living and inanimate particles are too small for your eye to see. But when billions to trillions of them aggregate in one place, we can see them from space. And these little things make a vast difference for life on Earth.

The particles in the air are known to atmospheric scientists as aerosols. Though the spray cans you might use for paint or hairspray do contain aerosols, the ones PACE will study are the flecks of carbon that rise from wildfires and smokestacks; the fine, dusty minerals that get lofted from deserts into the sky by strong winds; the nitrates and sulfates spewed by cars, trucks, and ships in their exhaust; and the salty spray from crashing waves and strong winds blowing over the ocean.

Why study them? Because those particles influence air quality, sometimes making it unhealthy to breathe, especially if you have asthma or heart and lung conditions. Pollution and smoke don’t observe borders – we all share Earth’s air — so it’s important to know something about the sources and types of particles floating around us. On the positive side, the bits of mineral dust or smoky aerosols can sometimes fertilize the ocean, providing nutrients for phytoplankton to bloom.

Aerosols also affect weather and climate. Tiny particles in the air reflect sunlight, and how much they reflect affects how much the land and ocean surfaces heat up. Aerosols also “seed” the formation of clouds: they provide surfaces on which water droplets form (condensation nucleii) as they aggregate into clouds. One of the great unknowns in our models of climate change is what role will aerosols will play in changing rainfall and snowfall patterns and in the heating or cooling of our atmosphere.

Though NASA has been studying aerosols from space for decades — observing where they are and the abundance of them — PACE and its SPEXone and HARP2 polarimeters will change the game. The instruments will tell us the shape and size of aerosols, helping us answer questions about where they come from and how they might influence other parts of the Earth system.

The other little things that PACE will examine have names like diatoms, coccolithophores, cyanobacteria, algae, and dinoflagellates. To borrow and mangle a quote from one of my favorite movie characters — Annie Savoy in Bull Durham — if you have three phytoplankton, they can’t do much. But if you have 300 billion of them, they can build a cathedral. Well, maybe not a cathedral, but they can develop into vast blooms that have a profound impact on life on this ocean planet.

Phytoplankton grow constantly on Earth and just about anywhere there are open, sunlit patches of water. When conditions are right, the growth of these microscopic cells can blossom to scales that are visible from orbit for days to weeks.

Phytoplankton are to the ocean what grasses and ground cover are to land: primary producers, a basic food source for other life, and the main carbon recycler for the marine environment. They are floating, plant-like organisms that soak up sunshine, sponge up nutrients, and create their own food (energy).

Why do we need to study these tiny organisms with PACE? While humans don’t really consume phytoplankton for food, the little floaters are fuel for the zooplankton, fish, and shellfish that we do eat. We also need to care about phytoplankton because they can influence water quality and human health. Some species of phytoplankton produce toxins that are dangerous to humans and animals; others can grow in such abundance that they crowd out other species or deplete the water of necessary oxygen.

Speaking of oxygen, phytoplankton produce a lot of it. Somewhere between 20 and 50 percent of the oxygen on Earth — some in our air, a lot in the ocean — is made by phytoplankton as they use photosynthesis to turn sunlight, carbon dioxide, and nutrients into sugars. In the process, they also draw carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere and, in time, sink it to the bottom of the ocean.

Better understanding the phytoplankton in the ocean will help us better understand the fisheries that feed us and our economy, and it can ultimately help us work toward cleaner waterways.

NASA and its research partners have been studying phytoplankton from space for decades, but mostly with just a few wavelengths of light. I am looking forward to the colors, textures, and details we will see with PACE’s OCI hyperspectral imager. As the PACE science team likes to say: we have been coloring the ocean with a box of 8 crayons, and now we are about to get a box with 128 shades of color. The leap in detail will allow scientists to better spot where phytoplankton are, but also figure out who (what species) they are.

And when PACE data are combined with observations from our recently launched SWOT mission — which studies the shape and movement of the surface of the ocean — it will be like going from the Earth-observing equivalent of the Hubble Space Telescope to the new James Webb Space Telescope.

Learn more about phytoplankton with these resources:

PACE Phytoplankton Exploration

The Insanely Important World of Phytoplankton

NASA Wants to Identify Phytoplankton Species from Space: Here’s Why.

As the Seasons Change, Will the Plankton?

Phytoplankton May Be Abundant Under Antarctic Sea Ice

Learn more about aerosols with these resources:

Just Another Day on Aerosol Earth

New NASA Satellite to Unravel Mysteries About Clouds, Aerosols

Global Transport of Smoke from Australian Bushfires

A few paths in life are short and direct; more of them are long and winding.

This week, a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket will launch from Cape Canaveral Space Force Station carrying the PACE satellite, short for Plankton, Aerosol, Cloud ocean Ecosystem. Once in orbit 676 kilometers (420 miles) above our planet, the newest addition to NASA’s fleet of Earth-observers will look at the oceans and land surfaces in more than 100 wavelengths of light from the infrared through the visible spectrum and into the ultraviolet. It will also examine tiny particles in the air by looking at how light is reflected and scattered (using a method like looking through polarized sunglasses).

The combination of measurements from the new satellite will give scientists and citizens a finely detailed look at life near the ocean surface, the composition and abundance of aerosols (such as dust, wildfire smoke, pollution, and sea salt) in the atmosphere, and how both influence and are affected by climate change.

For NASA and the ocean science community, the PACE launch will be the culmination of 9 or 46 years of work, depending on when you start counting. For me, it will be the culmination of something that started in 1950.

“There is a greater than 50 percent chance I will burst into tears at the launch,” said Jeremy Werdell, a satellite oceanographer at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center since 1999 and project scientist for PACE since 2015. “We are standing on the shoulders of previous missions and the people who led them. And it has been a long and remarkable journey.”

NASA’s first attempt at measuring ocean color dates back to the Coastal Zone Color Scanner (CZCS) instrument, which flew on the Nimbus 7 satellite from 1978-1986. In 1997, the agency launched the Sea-viewing Wide Field-of-view Sensor on the OrbView-2 satellite. SeaWiFS collected ocean data until 2010 and fundamentally changed our understanding of phytoplankton—microscopic, floating, plant-like organisms that are the grass of the sea. That sensor is an ancestor of the new Ocean Color Instrument (OCI) on PACE.

Other instruments and teams have observed the colors of the ocean. The Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) instruments on NASA’s Terra and Aqua satellites have been flying since 2000 and 2002, complementing and extending the record started by SeaWiFS. More recently, the Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite (VIIRS) instruments on the Suomi-NPP, NOAA-20, and NOAA-21 satellites have provided a broad view of ocean color. And several other instruments — like the Hyperspectral Imager for the Coastal Ocean (which flew on the space station), HawkEye (on the SeaHawk CubeSat), and the Ocean Radiometer for Carbon Assessment (which was flown on NASA research planes) — helped researchers test new ways to look at the sea.

For atmospheric scientists, the path to PACE also traces back across decades. In the late 1970s, the Advanced Very High Resolution Radiometer (AVHRR) provided some of the first looks at aerosol optical depth, a measure of how much dust and particles were floating in our skies. Later scientists began measuring such particles daily and around the world with the Multi-angle Imaging SpectroRadiometer and MODIS instruments on Terra. The OMI instrument on the Aura satellite, and its successor OMPS on Suomi-NPP, provided other unique views of aerosols. A HARP instrument flew on a CubeSat from 2019-2022 and provided a direct test of the technology that now flies on PACE as HARP2.

The origin of PACE itself sort of started around 2007. NASA and other federal agencies asked the U.S. National Research Council to study and suggest new tools and measurements for studying Earth from space. Their report (known as a “decadal survey“) recommended a mission that ultimately led to the A(erosol) and C(loud) components of the PACE mission. The inspiration for new ocean color sensors then arose from a NASA climate initiative proposed in 2010.

By 2012, NASA scientists and engineers were starting to sketch out rough ideas for PACE, and the wider science community dug into the details in 2014. By 2015, NASA Goddard started hiring for a new mission—including Jeremy Werdell—and by 2016, the agency had announced the formal development of a PACE mission.

Between that moment in 2016—known as Key Decision Point A—and this week’s launch there have been thousands of hours of work by hundreds of people…including many months working through a global pandemic…and the methodical, thoughtful testing of every idea, every design, and every part.

For me, the road to the PACE launch has also been long.

I have spent 21 years of my life working for NASA, and yet this will be my first launch. I feel blessed to spend my days working with incredibly talented, visionary, and smart people. This launch feels like the culmination of a lifetime geeking out on Earth and space science. Several threads of my life will all tie together this week.

In 1950, a 7th grader in Newark, New Jersey, won an essay contest by writing about a trip to the Moon. My father was fascinated by science fiction—he still is—and by journalism. He followed America’s developing space program with interest and, in 1969, his youngest son was born two weeks after the Apollo 11 Moon landing. Though no one can remember clearly, I like to say my parents named me for Michael Collins, who quietly orbited the Moon for 21 hours while Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin made the headlines below. (My mother often reminded me that she went through a similar 20+ painstaking hours of labor waiting for me to show up.)

On my first job as a magazine writer, I wrote in 1992 about the Mission to Planet Earth—first an international conference, then an early name for what became NASA’s Earth Observing System. I visited NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in 1994 to research my graduate thesis and by 1997 I had joined NASA Goddard, where I stayed for five years writing about space weather and space physics.

But then I traded one institution of exploration for another, leaving to write about ocean science for Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI). It was during those years on Cape Cod that I learned a boatload about phytoplankton and harmful algae. I spent 11 days at sea in 2005 on the research vessel Oceanus, helping scientists gather water samples to track a pesky, toxic phytoplankton called Alexandrium fundyense. After decades visiting the ocean, I was living by it and learning about it daily.

I rejoined NASA in 2008 and eventually joined Earth Observatory. Circumstances and generous colleagues allowed me to keep living by the sea, and so I brought my love of the ocean into my reporting. I also passed that love of the ocean and space to my children: Two have become marine biologists who study plankton, and one is an aerospace engineer working on satellites.

After so many years of my life intersecting with NASA and the sea, it just feels right that my first rocket launch should be a satellite that will bring us new eyes on Planet Ocean.

As previously stated, it is Cool like in Cool, CA.

Our first science meeting took place midway between T0 (McClellan Air Force Base) and T1 (Cool), so I couldn’t get a better chance to drive to the site that marks our downwind sampling location (T1, that is).

Off Rt. 80, you’ve got to follow the bends of 49 and down the gorge past Auburn, a real pretty town draped around the turns of historic Rt. 40. Then you drive up for another 4 miles past the Cool quarry.

Amidst this rural, very rural area, lies Northside Elementary school. Classes have been over for a week now, yet the backyard still hosts activity spurred by eternal kids with grey hair.

[youtube EX5qIuVhGWs 468]

This very repetitive bird emanates sound waves and the wind and

temperature in the atmosphere above are derived from their influence

on the speed of sound.

In trailers parked as control stations for ground instrumentation they are monitoring every spike in incoming particulates. Everything is very peaceful…trees, Sun, and even digital birds chirping.

Rushing back to the meeting, I found a room plenty with people anxious to display their first week of data. It is very important in the beginning of a campaign to make sure we establish a consistent baseline among all the different instruments.

Big discussions have already been engaged as to what pertains to local events as opposed to consistent transport patterns, but some points confirm the expectations. On a daily basis, a wide variety of small particles including black carbon get transported until they’re detected miles downwind from the sources, growing in size and getting coated with sulfates and other organics. More mysteries are hidden behind the unexpected amount of ultrafine particles, less than 10 nanometers in size (1 nanometer is a billionth of a meter). We’re not sure where they come from but they’re all around the urban areas.

Matteo

There’s nothing special about Sacramento’s urban emissions per se, other than being very typical emissions from a city. So why was the campaign designed to take place here? The thing is that this region has a very well defined circulation pattern, which makes the plume transport very regular.

Southwesterly winds mix two airflows in the afternoon. The first is a persistent flow originating in the San Francisco Bay area. The second is more local and due to air being heated up in the Sierras, which draws the cooler air from the valley. Unless — there is always an unless — the flow gets disrupted by synoptic (read: large scale) storms born in the Pacific. This is apparently what we have been observing in the first days of the campaign, doomed by an unusual amount of mid-level clouds. NASA’s instruments usually fly at around 8-9 km, and these clouds partly spoil our ability to observe aerosols beneath.

In any case, under normal conditions the resulting upslope flow transports the Sacramento’s plume towards the mountains, where anthropogenic aerosols interact with the biogenic sources from the forested areas, which are loaded with terpenes produced by the photosynthetic activity of vegetation. Recent research has shown that these biogenic sources could give an extra kick to the production of secondary organic aerosols of anthropogenic origin. “Secondary” here designates a zoo of different compounds generated by the interactions of “primary” substances with background conditions, leading to a myriad of chemical and physical transformations. An example? Humidity can coat aerosols of a thin film of water, drastically changing their properties.

The overall goal of the mission is to follow the evolution of the plume, sampling the formation of secondary organics and the anthropogenic/biogenic mixing ratio. Of great avail is the Cool “T1” site downwind from the sources here in Sacramento, packed with instrumentation on the ground managed by the Department of Energy. It’s Cool, like in Cool, CA. This nearly uninhabited site will be regularly overflown by the airplanes involved in the campaign so that data from the different platforms can be compared and validated. You can’t have ground sites everywhere, so that’s why the DOE G-1 airplane samples the area in between, trying to fill the gap and find out what happens in between. Plus there is us – the NASA group. We observe the same aerosols from high above, so we provide scene context. Our instruments are prototypes of those that fly on satellites in space, which are so very important because they give continuous global coverage via the “remote sensing” technique, or “the art of collecting data form a distance”. Very politically correct.

I have to thank Jerome Fast, who has extensive experience as chief meteorologist in campaigns like CARES, for his punctual forecast in the daily briefings and the explanations that prompted this post.

-Matteo