A few paths in life are short and direct; more of them are long and winding.

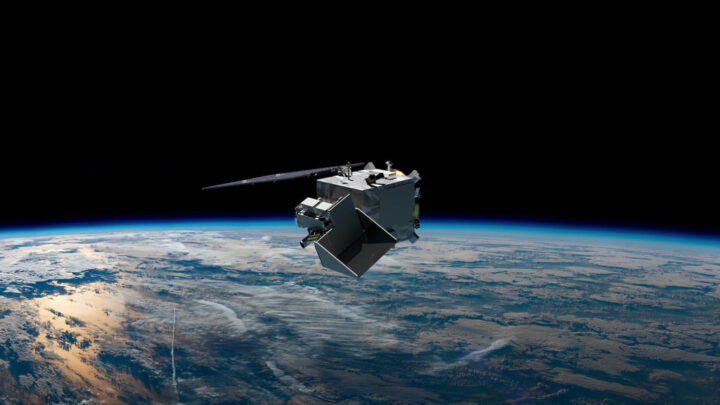

This week, a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket will launch from Cape Canaveral Space Force Station carrying the PACE satellite, short for Plankton, Aerosol, Cloud ocean Ecosystem. Once in orbit 676 kilometers (420 miles) above our planet, the newest addition to NASA’s fleet of Earth-observers will look at the oceans and land surfaces in more than 100 wavelengths of light from the infrared through the visible spectrum and into the ultraviolet. It will also examine tiny particles in the air by looking at how light is reflected and scattered (using a method like looking through polarized sunglasses).

The combination of measurements from the new satellite will give scientists and citizens a finely detailed look at life near the ocean surface, the composition and abundance of aerosols (such as dust, wildfire smoke, pollution, and sea salt) in the atmosphere, and how both influence and are affected by climate change.

For NASA and the ocean science community, the PACE launch will be the culmination of 9 or 46 years of work, depending on when you start counting. For me, it will be the culmination of something that started in 1950.

“There is a greater than 50 percent chance I will burst into tears at the launch,” said Jeremy Werdell, a satellite oceanographer at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center since 1999 and project scientist for PACE since 2015. “We are standing on the shoulders of previous missions and the people who led them. And it has been a long and remarkable journey.”

NASA’s first attempt at measuring ocean color dates back to the Coastal Zone Color Scanner (CZCS) instrument, which flew on the Nimbus 7 satellite from 1978-1986. In 1997, the agency launched the Sea-viewing Wide Field-of-view Sensor on the OrbView-2 satellite. SeaWiFS collected ocean data until 2010 and fundamentally changed our understanding of phytoplankton—microscopic, floating, plant-like organisms that are the grass of the sea. That sensor is an ancestor of the new Ocean Color Instrument (OCI) on PACE.

Other instruments and teams have observed the colors of the ocean. The Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) instruments on NASA’s Terra and Aqua satellites have been flying since 2000 and 2002, complementing and extending the record started by SeaWiFS. More recently, the Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite (VIIRS) instruments on the Suomi-NPP, NOAA-20, and NOAA-21 satellites have provided a broad view of ocean color. And several other instruments — like the Hyperspectral Imager for the Coastal Ocean (which flew on the space station), HawkEye (on the SeaHawk CubeSat), and the Ocean Radiometer for Carbon Assessment (which was flown on NASA research planes) — helped researchers test new ways to look at the sea.

For atmospheric scientists, the path to PACE also traces back across decades. In the late 1970s, the Advanced Very High Resolution Radiometer (AVHRR) provided some of the first looks at aerosol optical depth, a measure of how much dust and particles were floating in our skies. Later scientists began measuring such particles daily and around the world with the Multi-angle Imaging SpectroRadiometer and MODIS instruments on Terra. The OMI instrument on the Aura satellite, and its successor OMPS on Suomi-NPP, provided other unique views of aerosols. A HARP instrument flew on a CubeSat from 2019-2022 and provided a direct test of the technology that now flies on PACE as HARP2.

The origin of PACE itself sort of started around 2007. NASA and other federal agencies asked the U.S. National Research Council to study and suggest new tools and measurements for studying Earth from space. Their report (known as a “decadal survey“) recommended a mission that ultimately led to the A(erosol) and C(loud) components of the PACE mission. The inspiration for new ocean color sensors then arose from a NASA climate initiative proposed in 2010.

By 2012, NASA scientists and engineers were starting to sketch out rough ideas for PACE, and the wider science community dug into the details in 2014. By 2015, NASA Goddard started hiring for a new mission—including Jeremy Werdell—and by 2016, the agency had announced the formal development of a PACE mission.

Between that moment in 2016—known as Key Decision Point A—and this week’s launch there have been thousands of hours of work by hundreds of people…including many months working through a global pandemic…and the methodical, thoughtful testing of every idea, every design, and every part.

For me, the road to the PACE launch has also been long.

I have spent 21 years of my life working for NASA, and yet this will be my first launch. I feel blessed to spend my days working with incredibly talented, visionary, and smart people. This launch feels like the culmination of a lifetime geeking out on Earth and space science. Several threads of my life will all tie together this week.

In 1950, a 7th grader in Newark, New Jersey, won an essay contest by writing about a trip to the Moon. My father was fascinated by science fiction—he still is—and by journalism. He followed America’s developing space program with interest and, in 1969, his youngest son was born two weeks after the Apollo 11 Moon landing. Though no one can remember clearly, I like to say my parents named me for Michael Collins, who quietly orbited the Moon for 21 hours while Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin made the headlines below. (My mother often reminded me that she went through a similar 20+ painstaking hours of labor waiting for me to show up.)

On my first job as a magazine writer, I wrote in 1992 about the Mission to Planet Earth—first an international conference, then an early name for what became NASA’s Earth Observing System. I visited NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in 1994 to research my graduate thesis and by 1997 I had joined NASA Goddard, where I stayed for five years writing about space weather and space physics.

But then I traded one institution of exploration for another, leaving to write about ocean science for Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI). It was during those years on Cape Cod that I learned a boatload about phytoplankton and harmful algae. I spent 11 days at sea in 2005 on the research vessel Oceanus, helping scientists gather water samples to track a pesky, toxic phytoplankton called Alexandrium fundyense. After decades visiting the ocean, I was living by it and learning about it daily.

I rejoined NASA in 2008 and eventually joined Earth Observatory. Circumstances and generous colleagues allowed me to keep living by the sea, and so I brought my love of the ocean into my reporting. I also passed that love of the ocean and space to my children: Two have become marine biologists who study plankton, and one is an aerospace engineer working on satellites.

After so many years of my life intersecting with NASA and the sea, it just feels right that my first rocket launch should be a satellite that will bring us new eyes on Planet Ocean.