May 25, 2024

Some 25 of us were up before 6 a.m. to head out on the bus from the hotel to Burlington International Airport to catch the C-130 aircraft, a military transport plane repurposed for NASA fieldwork, to begin our 7-hour flight to Pituffik.

Several mountains of baggage, including scientific instruments and personal luggage, separate us from the less-well-heated economy cabin, which was probably reserved for graduate students, though we are far too collegial a group to check seat assignments. As we head north and east, the landscape out the window is vast, entirely gray-scale, and unforgiving: sea ice with streaks and patches of open water as far as one can see in every direction.

About halfway through the flight, we cross the Arctic Circle. Here the scene is often reduced to pure gray, and one cannot tell what is sea ice, snow, or cloud. This is the challenge we have long faced when attempting to interpret our remote sensing imagery; now, as an early gift of the expedition, I experience it directly.

May 26, 2024

The site is halfway between Washington and Moscow. Most or all of the buildings were prefabricated, brought here by ship in the summer, and mounted on stilts due to the permafrost. Some rough grasses are the only apparent vegetation.

In some ways, the base is well appointed. There is a sports center with an abundance of every conceivable exercise machine, also a tanning machine and a perpetual pool, a huge gym, and a yoga room. There is a recreation center with a movie theater, a lounge area with free apples, tea, and coffee, a game room that is more like an arcade with multiple video machines, and a craft center that has sewing machines (including a state-of-the-art Serger), rock cutting and polishing machines, computer graphics, and printers.

This is a remote place. The site is protected by a thousand kilometers of ice in nearly all directions, and the only ways to get here are by air or by boat for a couple of months of the year, when the sea is not frozen. With full daylight all day and “night,” the times-of-day are marked only by artificial clocks; the natural ones are essentially absent.

May 27, 2024

This was mostly a flight-planning day, getting ready for the first science flight of the campaign. It turned cold, windy, and snow fell today. This was more like what I expected but didn’t experience during the first two days. But now it is sunny again, around 6 p.m., and near-freezing, so there is still standing water on the roadways, and we are past the season when it is safe to walk on the ice-bound bay. The severe environment calls for some specific adaptations.

For example, the outer doors have latches that seal upward, so a bear pushing down on the handle will be unable to open the door. The walkways are made of open steel grids, so snow and mud will drip through. Boots are to be brushed before entering buildings, and plastic boot covers are provided in an effort to limit the amount of dirt that is tracked in.

I took a late-night walk. It’s daylight anyway, though overcast, windy, cold, and flurrying. Pretty much what I expected here.

The power went out twice today. Everything goes down, including the internet. I’m trying to keep everything charged, in case it happens again. Today’s weather represents “Condition Alpha” for storm warnings. That means just be on alert, in case things change. Condition Bravo means you cannot go outdoors without a buddy, or drive alone without a radio. Condition Charlie means you can’t walk out at all; there is a base taxi for urgent movement. Condition Delta: shelter in place.

The pipes are all above-ground because of the freeze-thaw cycle that would destroy the pipes. I guess they must be heated and insulated. They cross the road by going overhead.

Car and truck engines must be heated to avoid freezing and cracking. So, many of the buildings have power cords hanging out in front to run electric engine-block heaters. I didn’t take the last picture quite at midnight, but the scene doesn’t change much during the night.

I think I mentioned that it is mud season here. This is no joke. The place has a very industrial feel, and the only place to walk is on the mud roads. I’ve heard it will get worse as the mud deepens, and mosquitoes come out. Something to look forward to…

May 28, 2024

We had our first flight with the P3 today, and it was far better than I had expected. There was a rare case of cloud-free atmosphere over sea ice in one area north of Greenland where some buoys had been deployed, which allowed for both surface ice and aerosol characterization. Also, a nearly 3-hour run at ~500 feet captured aerosol properties over open water along the northern part of Baffin Bay. Among our objectives are learning the sources and properties of aerosols in the Arctic, their evolution as they age, and their impact on clouds. Others are especially interested in the properties of sea ice as it melts. So, this gives us a start on those objectives.

May 29, 2024

The wind is a force of nature. Today it has been blowing at something like 40 miles per hour, with gusts considerably higher. It literally takes your breath away—and this is just Condition Alpha.

Gusts create the sensation of blowing you away. All this under a relatively clear sky, bright sun, just a few clouds. It is somewhat other-worldly to one who has lived a life at lower latitudes. The temperature is only a few degrees below freezing, but the weather today gives new meaning to the term “wind chill.”

June 1, 2024

Today was an official day off, and in particular, a mental health day for the forecasters. Several of the military folks on the base arranged to take a group of us on a hike over the Greenland Ice Cap. There were 15 of us in five trucks. The trip involved a fair amount of driving on gravel roads in trucks—about half the time driving, half hiking – 5 hours total. The hike itself was about 5 or 6 miles, and we walked around and then on the glacier, though we never did find the Starbucks.

In addition to the stark beauty of the rock fields and ice, the sky is unlike anything we normally see at lower latitudes. The surface is cold, and the atmosphere is no colder (and sometimes is even warmer) than the surface, i.e., it is stably stratified—the “warm” air is already up, so there is not a lot of warm air rising and mixing that typically happens when the surface is heated directly by the Sun.

The glaciers have brought an enormous diversity of stones that litter the ground, and every piece of wood here was carried in from somewhere else. There are little clumps of vegetation, just enough to satisfy the appetites of musk oxen.

So far, I’ve seen Arctic fox (no pictures—they disappeared too quickly), musk ox in the distance, Arctic hare, and snow goose. No polar bears—and no complaints about that.

June 7, 2024

This evening I took a long walk out to the ice-bound pier… AND I SAW AN OTTER!!!

June 4, 2024

The Arctic foxes are molting. They were very cute when their coats were all white. Now they are losing their winter coats and turning brown. I did see a couple of full white coats, but was too slow to get a photo.

June 8, 2024

The project rented a van, and ten of us went off to climb the Dundas, that imposing rock feature not far from the base, though to get there without walking on thin ice (here the term is not merely a metaphor), one has to drive about 30 minutes over rocky and sometimes quite steep roads around the frozen bay.

The angle of repose is the angle a pile of dry sand (or salt) will make if you dump a bucket of it on the ground. It is generally steep (depends in part on the grain size and shape of the sand particles). Dundas is about 725 feet high; it appears to be the remnant of a glacial moraine—rock pushed here by an advancing ice sheet at least that high, that remained after the ice melted away. It is loose sand and rock, mostly gravel and cobble-sized. The climb up was, frankly, arduous, as there are not a lot of footholds.

The first part was steep enough that going on all fours was necessary in places, and the sand and small rocks would slip easily down the slope as one persevered upward. The final part was up a sheer rock wall that was graced, mercifully, with a sturdy rope. My pictures are lacking for the entire traverse, as all my effort went into the climb itself. I did stop part way up the rock wall to check my life insurance policy.

The view from the top was spectacular, but truthfully, there are so many great vistas in this rugged place that the main reward was accomplishing the ascent itself.

The way down was similarly fraught, except that below the rock wall, I had pretty much no choice but to slide down bit by bit—the loose surface material would give way at every step. So, on my back, lift up my rear, slide a few feet using my boots to stop, and repeat. There was some interesting vegetation on the slope—tiny plants and lichen, which I did photograph. I’m told that some of these plants can be hundreds of years old.

In the distance, we saw some dark spots that the binoculars suggested were seals. (Oh, yes—someone here said that my otter from last night was actually a ring seal; not sure that is authoritative, but…).

June 9, 2024

I agreed to join this afternoon’s walk up the edge of the Greenland Ice Sheet.

The slope is moderate by Dundas standards, and the path is completely snow-covered. The walk up is of course uphill, and a steady wind of 30–40 mph (the katabatic wind), with significantly higher gusts, blows off the ice. This guaranteed that however far we got up the ice sheet, we would certainly be able to make it down, either on foot or airborne.

There were pools of water within ice basins at the base. They look a beautiful shade of blue. We saw this in Alaska as well. I think it must be that ice either absorbs all the longer wavelengths, or it preferentially scatters blue, or both. The optics here are stunning, at least to me. Probably because they are unfamiliar.

One way painters provide a sense of distance in a painting is with “atmospherics,” that is, they increasingly blur the edges of more distant objects to account for light scattering by atmospheric gas and aerosols. Mountain climbers experience the opposite, in the thinner atmosphere, remote objects are sharper than they would in everyday experience, so more distant objects appear closer than they actually are. This is true here in Greenland as well, though we are not at a very high elevation along the coast. I expect the phenomenon in this case is due to a very clean atmosphere.

June 11, 2024

Today I got to fly on the P-3. Every satellite scientist should be required to take at least one such flight to see what the Earth is really like. We flew across northern Greenland and over sea ice. In the two weeks since the campaign deployment began, the depth of the sea ice, and the snow upon it, both decreased at those buoys (where it was measured), and, of course, most everywhere else as well.

A field campaign is a layered operation. Aircraft flight scientists build, run, and maintain the twenty or so instruments that measure particle composition, gas concentration, cloud properties, surface reflectivity, and upwelling and downwelling energy. They are awake by 4 a.m. to prepare their instruments for flight, worry about power supplies and calibration, then sit on the plane for six or seven hours, noting what they see from their measurements and out the window.

The number of leads (i.e., openings in the ice) has increased in places. We flew at high elevation to survey the area, measure the overall surface topography and reflectance, and sample aerosol layers aloft, then descended to 300 feet above the ice to capture aerosols emanating from the surface. The photos tell an accessible part of the story. The rest must be teased out of the data in the coming months and years. But my ride is over for now—there is an aerosol forecast due tomorrow.

June 12, 2024

It was flurrying this evening, and my walk carried me down toward the pier. But you might be pleased to know, I did not go all the way; several seals have now been seen on the ice at the pier. My otter or seal in the water was the first anyone saw, and although they say it is relatively rare for bears to go near the base, seals are their primary food. I figured, after a long winter hibernation, a bear might not count me as even a light snack, but in consideration that I had already booked my flight home, I turned around before getting very near the water’s edge.

June 14, 2024

I should say that the food here is okay. Better than I expected. Of course, in such circumstances, it pays to begin with low expectations: hardtack, pemmican, and beef jerky. The cafeteria serves a lot of beef and pork, but there is also chicken, a reasonable salad bar, excellent, fresh bread (the highlight in my opinion), always two of THE three kinds of fruit (apples, oranges, and bananas—so yes, they mix apples and oranges), and of course, Danish, at least in the morning.

In the evening I took a walk, as usual, and ended up in one of the dozens of prefab buildings on the base, with the suggestive label “Heritage Hall.” The door was not locked, and the lights turned on as you entered each room. The place is a sort of museum, a repository for things discarded from the 1950s and 60s.

They have a computer punch-card machine, a vacuum-tube TV set, and a radar scope you will recognize from science-fiction movies. Also some notebooks with photos of the army’s Camp Tuto (now abandoned—only remnants of the airfield remain) and the presumptive city “Camp Century” they built into the ice in the 1950s. The walls flowed at glacial speed but ultimately collapsed.

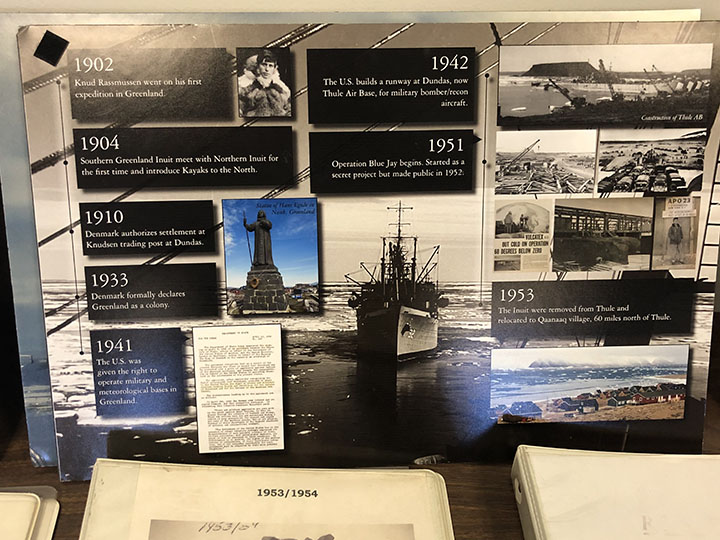

Thule base was established in 1951, succeeding three waves of Inuit who inhabited the area, apparently beginning 4,500 years ago. The most recent came around 900 CE, met the Norse about 100 years later, and were moved to a new village 60 miles to the north in 1953. There is even a Life Magazine cover showing ships delivering material to the base in September 1952.

Ralph Kahn, an emeritus research scientist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center now at the Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics at the University of Colorado Boulder, spent three weeks at Pituffik Space Base in northern Greenland in the summer of 2024. He was one of dozens of scientists who participated in ARCSIX (Arctic Radiation-Cloud Aerosol-Surface Interaction Experiment), a NASA-sponsored field campaign that made detailed observations of clouds and atmospheric particles to better understand the processes that affect the seasonal melting of Arctic sea ice. These excerpts from his emails home to family provide a glimpse of what life was like on one of the world’s most northern scientific outposts in the world. Photos were taken by Kahn or Gary Banzinger, a NASA videographer who also participated in the campaign. Kahn, an atmospheric scientist, worked with colleagues to provide daily aerosol forecasts that were used to help plan flights.

Tom and I have returned to McMurdo Station!

Our traverse is complete, our gear has been stored for next season, and we are ready to head north to warmer climates. But in the meantime, we are awaiting our flight to Christchurch, New Zealand, at Antarctica’s largest research station.

McMurdo Station from above (Photo: Tom Neumann)

McMurdo is one of three permanent US research stations in Antarctica. The other two are Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station and Palmer Station, which is south of South America. McMurdo has beds for approximately 1,000 people, but while we have been here, the population has hovered between about 750 and 825.

While there is a research station operated by New Zealand just 2 km away, McMurdo is relatively isolated. As such, there are facilities here that provide all of the basic essentials required for living in the polar regions, such as power, heat, and water. McMurdo has its own diesel-based power plant, providing lights and heat to the station. The station gets its fresh water through the desalinization of the sea water in the neighboring bay via a method called reverse osmosis. And McMurdo has its own waste-water treatment facility. To operate a station this size, and in this environment, McMurdo also requires an airfield, a galley, and all of the staffing that goes along with running a small town. It is quite an operation.

McMurdo on a snowy day, with the chapel in the background. (Photo: Kelly Brunt)

McMurdo station also has specialized facilities that support the cutting-edge science that happens here. These facilities include a sophisticated laboratory that is capable of housing a cross section of Antarctic research disciplines such as glaciology, geology, meteorology, and biology.

The research that takes place here also includes really cool meteorite science! The search for meteorites is a bit simpler here than in other parts of the world. Since Antarctica is a thick sheet of ice, rocks found on the top of the ice sheet are often associated with debris fallen from space; these meteorites stand out against the white surface. Plus, the flow of the ice organizes the meteorites, making them more centralized for collection. Some of our colleagues from NASA Goddard Space Flight Center are part of this effort.

The U.S. Coast Guard Cutter Polar Star, in McMurdo Sound. (Photo: Tom Neumann)

The pier in town is currently the busiest spot on station. The US Coast Guard Cutter Polar Star has cleared a channel into McMurdo Sound, giving three other vessels access to town. The first is the Nathaniel B. Palmer, the US Antarctic Program’s premier research vessel, which has been in town for the past few days. Simultaneously, the entire station is preparing for the arrival of the two other ships: the tanker Maersk Peary brings in the annual fuel supply, and the Ocean Giant cargo ship brings in the food and supplies for the following year.

The Nathaniel B. Palmer in McMurdo Sound (Photo: Kelly Brunt)

Tom and I are scheduled to leave McMurdo on the next flight. But the weather has deteriorated and we are left patiently waiting for it to clear. We are extremely happy with our successful field season and have had a fantastic trip. Thanks for reading and following along.

-Kelly & tom

The 88S traverse was very much a group effort – in addition to the four of us, literally hundreds of people supported our project to varying degrees. This is not at all uncommon for work in Antarctica: no one person can do everything, and each person brings some unique skill to the effort.

Chad at the helm of ‘Hans,’ our trailing PistenBully (the lead vehicle was dubbed Gretel). Chad was always pleased at the end of a successful day of driving. (Photo: Kelly Brunt)

Without the vehicles, there would have been no traversing, and our mechanic Chad Seay deserves the credit for keeping us moving. Chad spent a furious week before we left South Pole servicing and repairing our two PistenBully tracked vehicles to try to head off potential complications in the field. It’s much easier to fix problems in the relative warmth of the garages at South Pole than out at 87.979 south latitude. In addition, Chad kept a careful eye on our generators and emergency heat source (the venerable Hermann Nelson). Chad picked up the knack for wrenching growing up among the farms of eastern Tennessee, and has honed his skills in the vehicle shop at McMurdo Station. His attention to detail is second to none, and his seemingly inexhaustible supply of PistenBully-branded clothing was reassuring.

Forrest piloting the lead vehicle, on the look out for danger and the missing box of Slim Jims. (Credit: Chad Seay)

Our safety and well-being were the purview of Forrest McCarthy, our mountaineer and medic. Forrest led our field safety training in McMurdo and brought literally decades of experience in the mountains and polar regions to lead us through potential scenarios and how to deal with them. While none of these (thankfully) came to pass during our traverse, being prepared is an important component of staying safe. Forrest was nearly always the first one up in the morning, and had coffee (stove top espresso) and hot water ready for all. He drove the lead vehicle the entire way, and his unfailing good humor was always welcome, and his taste for Slim Jims was a source of entertainment, at least for me.

Kelly behind the wheel, smiling at how well everything is going. (Credit: Tom Neumann)

Kelly was the overall leader for the trip, and kept track of an impressive array of details, while not losing sight of the overall science goals of the traverse. Although this was her first foray into traversing the frozen plateau, Kelly kept us going in the right direction. (literally! Who else would have corrected 88S to 87.979S?) Though I knew Kelly was a coffee connoisseur, her dedication to a morning pour-over was a dependable part of our morning routine.

Tom with one of the hundreds of cargo straps that held everything together. (Credit: Chad Seay)

I rounded out the quartet and rode shotgun with Forrest. My main duties were to run the ground penetrating radar, and partake of both the stove top espresso and pour-over each day. Having done a couple of traverses across the plateau, my other main duty was to offer sage advice and/or witty comments as the situation warranted. At least that’s what I think I did – Chad, Kelly and Forrest may have a different opinion!

We all shared in the cooking and cleaning duties, and managed to keep ourselves fed and happy. Some highlights were Chad’s frozen burritos (and he claimed he couldn’t cook?!), my tiny pizzas, and a truly massive amount of cookies and cream ice cream. While the ice cream was good, we always required a hot drink immediately afterwards: the kitchen tent was warm, but perhaps not warm enough to make eating ice cream a really good idea.

In addition to the four of us, there really were a multitude of others here in Antarctica and beyond who made the traverse such a success. While not a complete list, we all want to thank (in no particular order): Tim, Jen, Ian, Bjia, Kory, Steve Z, Chad, Curt, Autumn (what ice cream?), Liz, Joey, Tony, Michael, Dan & Danny, Tony, Stacy, James, JD (who just makes things happen), Jen, Marlene, Darren, Andrea, Joni, Zoe, Annie, and Thorsten.

Trip isn’t over yet folks – we’re re-packing cargo and heading back to McMurdo shortly…

-Tom and Kelly

We smashed it.

Our team is back at South Pole Station after a highly successful 88S Traverse. We budgeted 16 to 19 days for the traverse, but we returned to station after just 15 days. Our science instrumentation and the vehicles performed with only minor hiccups, and in general, any problems that arose were solved quickly.

PistenBullys on traverse! Two tracked vehicles hauling the living quarters and equipment for the folks on the 88S Traverse. (Photo: Chad Seay)

The campaign by the numbers: 750 km (or 466 miles) of ground traverse; 15 days; 4 people; 2 PistenBullys; 4 corner cube reflector arrays; many snack, including an irrational number of Slim Jims; ~3 lbs of coffee; 1 giant tub of ice cream; and way too much CCR, Ozzy, and Styx.

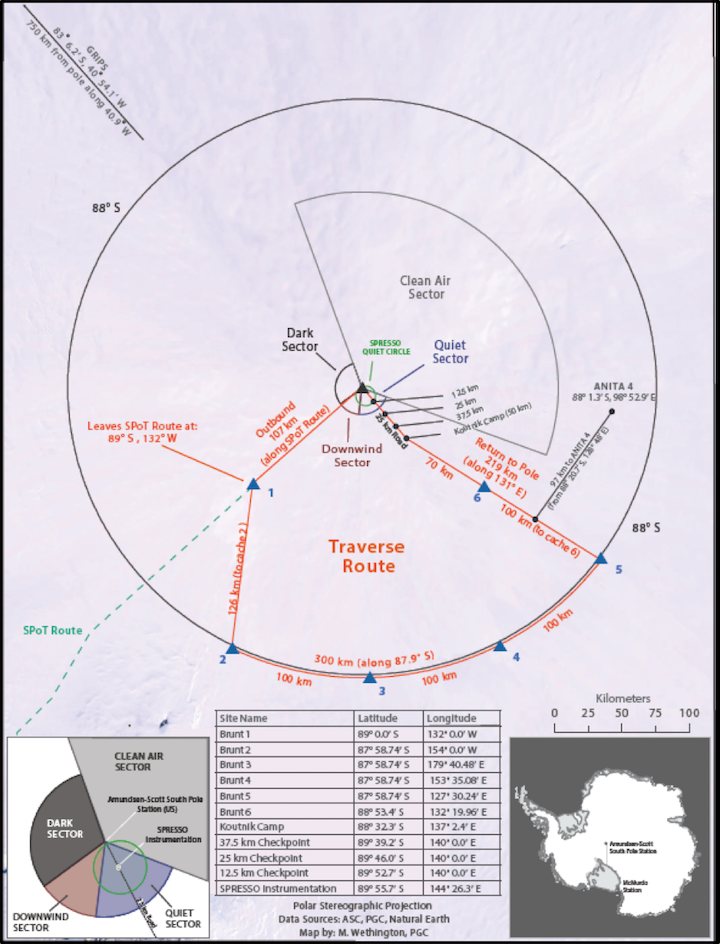

But first – 4 days to get to our study area! To reach the southern extent of the ICESat-2 ground tracks at 88 degrees latitude, where we’ll take ground measurements to compare with future satellite data, we had to drive 220 km (137 miles) from the South Pole. We collected GPS elevation data along the way, in part to get ourselves up to speed with the day-to-day business of data collection and in part because there is very limited ground-based elevation data in this region.

The first 110 km (68 miles) of this was on the established, groomed, South Pole Traverse route, which had been driven three times this season as teams delivered fuel to South Pole Station. But after that, we were on our own…

The polar plateau, interrupted by PistenBully tracks. (photo: Kelly Brunt)

We turned left off of the South Pole Traverse route and began breaking new ground. After another 110 km, we were on the 88S line of latitude!

Almost instantly, we arrived at a point where Tom and I wanted to deploy an array of corner cube retroreflectors (CCRs), which are made of specialized glass that will strongly reflect the transmitted signal from ICESat-2. These points of strong reflection will be used to validate the pointing of ICESat-2.

The CCRs are insanely small, smaller than your pinky nail. Setting up the first array of 6 CCRs took about half a day, as we mounted the CCRs on the top of bamboo poles and then precisely located the position of the bamboo poles by occupying the site of each pole with a survey-quality GPS for 20 minutes. Since most of this was accomplished outside, you can imagine that this was a pretty cold morning. Ultimately, we deployed 4 CCR arrays along the 88S route.

A insanely small corner cube retroreflector, mounted on a bamboo pole (Photo: Tom Neumann)

With the exception of the areas associated with the CCR arrays (and yes, every time I say ‘CCR’, Tom sings a John Fogerty classic; it’s true even in his reading of this), the bulk of our days were consumed with driving. We averaged about 60 km (37 miles) per day, at a breakneck speed of about 9 km/hr (5.6 mph).

And as with any road trip, we consumed a lot of road snacks, including chips, jerky, and in the case of our mountaineer Forrest, many, many Slim Jims.

After about a week on the 88S line of latitude, we reached a point where we had collected our goal: 300 km (186 miles) of ground-based elevation data for direct comparison with ICESat-2 elevation data. Forrest fired up Ozzy’s ‘Mama, I’m Coming Home’ in his PistenBully and we made our second left turn, toward Pole.

The sled train headed south toward the Pole, and ultimately toward home (Photo: Chad Seay)

From 88S, we again traveled 220 km to traverse from our study area to Pole. We continued to collect data along this stretch, but our focus turned to the tired PistenBullys, which are 17 years old and not accustomed to two straight weeks of intense usage. Our incredible mechanic Chad kept an eye on these and helped to nurse them home.

We did so well, that I was overly conservative on consumption of really good coffee: I made Tom drink mediocre coffee for about a week, before I felt confident that the really good coffee would last the whole traverse. For this, Tom, I am eternally sorry.

Hey Eileen: Mama, I’m coming home.

-Kelly and Tom

By the time this hits the press, we will be well on our way. After building the sleds, tuning up the PistenBullys, and going for a couple of test drives around the station, we are about as ready as we are ever going to be. Onward!

Our route travels north along the South Pole Operational Traverse route for about 100km, then turns left and heads out to 87.979 degrees south. 750 kilometers of the great flat white!

While on the road, we will be staying the tents that Kelly described in her last post. Really, tents? Isn’t it cold down there? We expect the daytime temperatures to be in the -20F to -30F (-29C to -34C) range with relatively light winds and sunny skies. These tents warm up nicely in the sun, and will warm up to a good 30 degrees warmer than the outdoor air temperature. That makes the interior a balmy 10F (-12C), which is really not too bad.

Our kitchen tent is the largest tent and will accommodate all four of us. Along the back wall, we have fashioned a counter out of a box and an aluminum kitchen table. The cooking supplies, including a two-burner stove that uses white gas, are stored either in the box, or in the two purple kitchen boxes. Generally, only one or two of us are in here at a time when cooking, as a little elbow room goes a long way.

Who wouldn’t want to cook in here – look at that counter space!

We each have our own mountain tent for sleeping. It’s always nice to have some personal space, and the multiple air mattresses, foam pads, and super warm sleeping bags make for a pretty comfortable evening. A couple of Christmas lights, some magazines, and it’s home sweet home for the next three weeks.

A super-warm down sleeping bag, plus Christmas lights, make for a comfortable tent.

Days are spent in our PistenBullys, collecting the GPS data of the ice sheet surface using survey-grade GPS systems that will be a critical piece of the ICESat-2 validation effort. We will spend about 300 kilometers around the 87.979 S line of latitude where the ICESat-2 data will be the densest. By comparing our measurements of the ice sheet elevation from the ground traverse, with the elevation measured by ICESat-2 on orbit, we will assess the quality of our on-orbit data and make any corrections necessary. We aim to cover our route in about three weeks and be back here at South Pole around mid-January. Happy New Year, and happy birthday Mom!

We’ll catch you in a couple of weeks!

-Tom and Kelly