It’s that time of year again: Time to conduct another 88S Traverse! We have made it to Antarctica for a second straight year, in support of NASA’s ICESat-2. You can read all of our posts, including those from the 2017-2018 88S Traverse here. And here’s a fantastic video that describes last season’s traverse in great detail.

After a quick stop in Christchurch, New Zealand, we made it to McMurdo Station, which sits on the coast of Antarctica.

The 88S Traverse is a ground-based survey intended to collect highly accurate and precise GPS elevation data for direct comparison with ICESat-2 surface height data. The traverse is conducted using 2 PistenBully tracked-vehicles that pull our camping equipment and science instrumentation along the ice sheet. ICESat-2 is a satellite laser altimeter, designed to measure the surface of the Earth to an accuracy and precision of something on the order of the width of a pencil! Our goal with the 88S Traverse is to validate that ICESat-2 is meeting that level of accuracy and precision.

This season is a bit special; ICESat-2 was launched earlier this year, making this the first 88S Traverse that will be coordinated with the satellite observations. ICESat-2 launched in the wee hours of September 15, 2018. And even though it was a super early morning for me, and I did not have enough coffee in my system, the event was spectacular. ICESat-2 is currently collecting data globally, including over our field area around 88S, with the expectation of releasing these data to the public in early 2019.

More recently, NASA’s Operation IceBridge completed their Antarctic field campaign. Their flight plans included surveying the 88S Traverse route. The actual flight over our area occurred on November 12, 2018. Our survey area doesn’t change that much over short time scales. There isn’t very much snowfall (input) and it’s very cold, so there is almost no melt (output). The processes that change the surface at a detectable level happen at much greater time scales. These include compaction of snow that falls over time on the surface (we call this firn compaction) and snow migration form the wind. Therefore, the November data collected by IceBridge will be very comparable to the data that we will collect, less than two months later.

We are currently at McMurdo, waiting for weather to clear so that we can get to the South Pole. From there, we will take about a week to build the sled platforms, and then we hit the road. And by the end of our field season, we will have ground-based, airborne, and satellite data for comparison!

Tom and I have returned to McMurdo Station!

Our traverse is complete, our gear has been stored for next season, and we are ready to head north to warmer climates. But in the meantime, we are awaiting our flight to Christchurch, New Zealand, at Antarctica’s largest research station.

McMurdo Station from above (Photo: Tom Neumann)

McMurdo is one of three permanent US research stations in Antarctica. The other two are Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station and Palmer Station, which is south of South America. McMurdo has beds for approximately 1,000 people, but while we have been here, the population has hovered between about 750 and 825.

While there is a research station operated by New Zealand just 2 km away, McMurdo is relatively isolated. As such, there are facilities here that provide all of the basic essentials required for living in the polar regions, such as power, heat, and water. McMurdo has its own diesel-based power plant, providing lights and heat to the station. The station gets its fresh water through the desalinization of the sea water in the neighboring bay via a method called reverse osmosis. And McMurdo has its own waste-water treatment facility. To operate a station this size, and in this environment, McMurdo also requires an airfield, a galley, and all of the staffing that goes along with running a small town. It is quite an operation.

McMurdo on a snowy day, with the chapel in the background. (Photo: Kelly Brunt)

McMurdo station also has specialized facilities that support the cutting-edge science that happens here. These facilities include a sophisticated laboratory that is capable of housing a cross section of Antarctic research disciplines such as glaciology, geology, meteorology, and biology.

The research that takes place here also includes really cool meteorite science! The search for meteorites is a bit simpler here than in other parts of the world. Since Antarctica is a thick sheet of ice, rocks found on the top of the ice sheet are often associated with debris fallen from space; these meteorites stand out against the white surface. Plus, the flow of the ice organizes the meteorites, making them more centralized for collection. Some of our colleagues from NASA Goddard Space Flight Center are part of this effort.

The U.S. Coast Guard Cutter Polar Star, in McMurdo Sound. (Photo: Tom Neumann)

The pier in town is currently the busiest spot on station. The US Coast Guard Cutter Polar Star has cleared a channel into McMurdo Sound, giving three other vessels access to town. The first is the Nathaniel B. Palmer, the US Antarctic Program’s premier research vessel, which has been in town for the past few days. Simultaneously, the entire station is preparing for the arrival of the two other ships: the tanker Maersk Peary brings in the annual fuel supply, and the Ocean Giant cargo ship brings in the food and supplies for the following year.

The Nathaniel B. Palmer in McMurdo Sound (Photo: Kelly Brunt)

Tom and I are scheduled to leave McMurdo on the next flight. But the weather has deteriorated and we are left patiently waiting for it to clear. We are extremely happy with our successful field season and have had a fantastic trip. Thanks for reading and following along.

-Kelly & tom

The 88S traverse was very much a group effort – in addition to the four of us, literally hundreds of people supported our project to varying degrees. This is not at all uncommon for work in Antarctica: no one person can do everything, and each person brings some unique skill to the effort.

Chad at the helm of ‘Hans,’ our trailing PistenBully (the lead vehicle was dubbed Gretel). Chad was always pleased at the end of a successful day of driving. (Photo: Kelly Brunt)

Without the vehicles, there would have been no traversing, and our mechanic Chad Seay deserves the credit for keeping us moving. Chad spent a furious week before we left South Pole servicing and repairing our two PistenBully tracked vehicles to try to head off potential complications in the field. It’s much easier to fix problems in the relative warmth of the garages at South Pole than out at 87.979 south latitude. In addition, Chad kept a careful eye on our generators and emergency heat source (the venerable Hermann Nelson). Chad picked up the knack for wrenching growing up among the farms of eastern Tennessee, and has honed his skills in the vehicle shop at McMurdo Station. His attention to detail is second to none, and his seemingly inexhaustible supply of PistenBully-branded clothing was reassuring.

Forrest piloting the lead vehicle, on the look out for danger and the missing box of Slim Jims. (Credit: Chad Seay)

Our safety and well-being were the purview of Forrest McCarthy, our mountaineer and medic. Forrest led our field safety training in McMurdo and brought literally decades of experience in the mountains and polar regions to lead us through potential scenarios and how to deal with them. While none of these (thankfully) came to pass during our traverse, being prepared is an important component of staying safe. Forrest was nearly always the first one up in the morning, and had coffee (stove top espresso) and hot water ready for all. He drove the lead vehicle the entire way, and his unfailing good humor was always welcome, and his taste for Slim Jims was a source of entertainment, at least for me.

Kelly behind the wheel, smiling at how well everything is going. (Credit: Tom Neumann)

Kelly was the overall leader for the trip, and kept track of an impressive array of details, while not losing sight of the overall science goals of the traverse. Although this was her first foray into traversing the frozen plateau, Kelly kept us going in the right direction. (literally! Who else would have corrected 88S to 87.979S?) Though I knew Kelly was a coffee connoisseur, her dedication to a morning pour-over was a dependable part of our morning routine.

Tom with one of the hundreds of cargo straps that held everything together. (Credit: Chad Seay)

I rounded out the quartet and rode shotgun with Forrest. My main duties were to run the ground penetrating radar, and partake of both the stove top espresso and pour-over each day. Having done a couple of traverses across the plateau, my other main duty was to offer sage advice and/or witty comments as the situation warranted. At least that’s what I think I did – Chad, Kelly and Forrest may have a different opinion!

We all shared in the cooking and cleaning duties, and managed to keep ourselves fed and happy. Some highlights were Chad’s frozen burritos (and he claimed he couldn’t cook?!), my tiny pizzas, and a truly massive amount of cookies and cream ice cream. While the ice cream was good, we always required a hot drink immediately afterwards: the kitchen tent was warm, but perhaps not warm enough to make eating ice cream a really good idea.

In addition to the four of us, there really were a multitude of others here in Antarctica and beyond who made the traverse such a success. While not a complete list, we all want to thank (in no particular order): Tim, Jen, Ian, Bjia, Kory, Steve Z, Chad, Curt, Autumn (what ice cream?), Liz, Joey, Tony, Michael, Dan & Danny, Tony, Stacy, James, JD (who just makes things happen), Jen, Marlene, Darren, Andrea, Joni, Zoe, Annie, and Thorsten.

Trip isn’t over yet folks – we’re re-packing cargo and heading back to McMurdo shortly…

-Tom and Kelly

We smashed it.

Our team is back at South Pole Station after a highly successful 88S Traverse. We budgeted 16 to 19 days for the traverse, but we returned to station after just 15 days. Our science instrumentation and the vehicles performed with only minor hiccups, and in general, any problems that arose were solved quickly.

PistenBullys on traverse! Two tracked vehicles hauling the living quarters and equipment for the folks on the 88S Traverse. (Photo: Chad Seay)

The campaign by the numbers: 750 km (or 466 miles) of ground traverse; 15 days; 4 people; 2 PistenBullys; 4 corner cube reflector arrays; many snack, including an irrational number of Slim Jims; ~3 lbs of coffee; 1 giant tub of ice cream; and way too much CCR, Ozzy, and Styx.

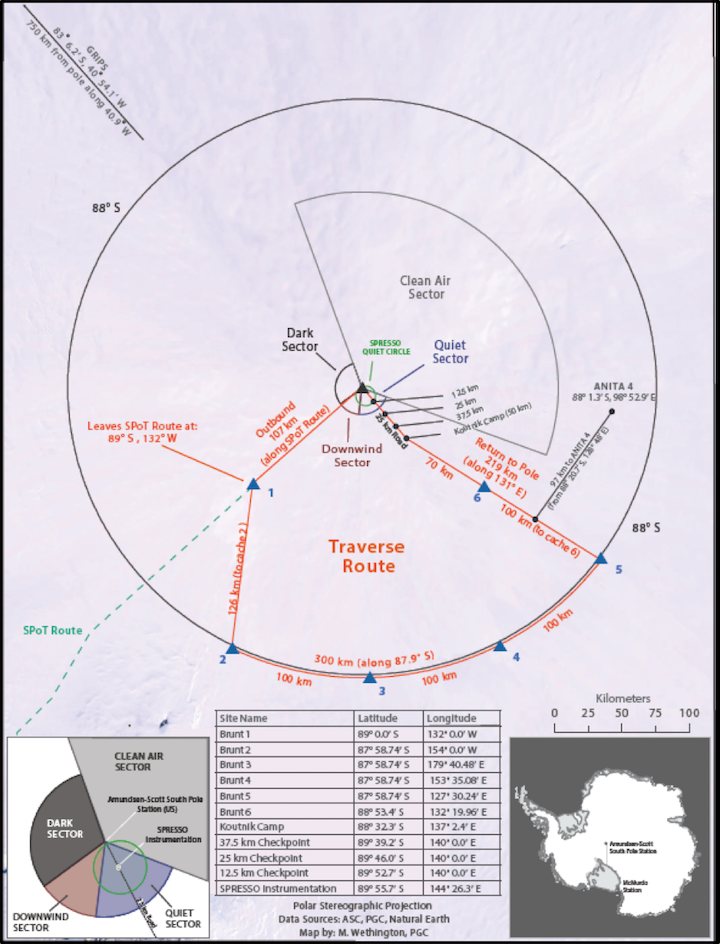

But first – 4 days to get to our study area! To reach the southern extent of the ICESat-2 ground tracks at 88 degrees latitude, where we’ll take ground measurements to compare with future satellite data, we had to drive 220 km (137 miles) from the South Pole. We collected GPS elevation data along the way, in part to get ourselves up to speed with the day-to-day business of data collection and in part because there is very limited ground-based elevation data in this region.

The first 110 km (68 miles) of this was on the established, groomed, South Pole Traverse route, which had been driven three times this season as teams delivered fuel to South Pole Station. But after that, we were on our own…

The polar plateau, interrupted by PistenBully tracks. (photo: Kelly Brunt)

We turned left off of the South Pole Traverse route and began breaking new ground. After another 110 km, we were on the 88S line of latitude!

Almost instantly, we arrived at a point where Tom and I wanted to deploy an array of corner cube retroreflectors (CCRs), which are made of specialized glass that will strongly reflect the transmitted signal from ICESat-2. These points of strong reflection will be used to validate the pointing of ICESat-2.

The CCRs are insanely small, smaller than your pinky nail. Setting up the first array of 6 CCRs took about half a day, as we mounted the CCRs on the top of bamboo poles and then precisely located the position of the bamboo poles by occupying the site of each pole with a survey-quality GPS for 20 minutes. Since most of this was accomplished outside, you can imagine that this was a pretty cold morning. Ultimately, we deployed 4 CCR arrays along the 88S route.

A insanely small corner cube retroreflector, mounted on a bamboo pole (Photo: Tom Neumann)

With the exception of the areas associated with the CCR arrays (and yes, every time I say ‘CCR’, Tom sings a John Fogerty classic; it’s true even in his reading of this), the bulk of our days were consumed with driving. We averaged about 60 km (37 miles) per day, at a breakneck speed of about 9 km/hr (5.6 mph).

And as with any road trip, we consumed a lot of road snacks, including chips, jerky, and in the case of our mountaineer Forrest, many, many Slim Jims.

After about a week on the 88S line of latitude, we reached a point where we had collected our goal: 300 km (186 miles) of ground-based elevation data for direct comparison with ICESat-2 elevation data. Forrest fired up Ozzy’s ‘Mama, I’m Coming Home’ in his PistenBully and we made our second left turn, toward Pole.

The sled train headed south toward the Pole, and ultimately toward home (Photo: Chad Seay)

From 88S, we again traveled 220 km to traverse from our study area to Pole. We continued to collect data along this stretch, but our focus turned to the tired PistenBullys, which are 17 years old and not accustomed to two straight weeks of intense usage. Our incredible mechanic Chad kept an eye on these and helped to nurse them home.

We did so well, that I was overly conservative on consumption of really good coffee: I made Tom drink mediocre coffee for about a week, before I felt confident that the really good coffee would last the whole traverse. For this, Tom, I am eternally sorry.

Hey Eileen: Mama, I’m coming home.

-Kelly and Tom

By the time this hits the press, we will be well on our way. After building the sleds, tuning up the PistenBullys, and going for a couple of test drives around the station, we are about as ready as we are ever going to be. Onward!

Our route travels north along the South Pole Operational Traverse route for about 100km, then turns left and heads out to 87.979 degrees south. 750 kilometers of the great flat white!

While on the road, we will be staying the tents that Kelly described in her last post. Really, tents? Isn’t it cold down there? We expect the daytime temperatures to be in the -20F to -30F (-29C to -34C) range with relatively light winds and sunny skies. These tents warm up nicely in the sun, and will warm up to a good 30 degrees warmer than the outdoor air temperature. That makes the interior a balmy 10F (-12C), which is really not too bad.

Our kitchen tent is the largest tent and will accommodate all four of us. Along the back wall, we have fashioned a counter out of a box and an aluminum kitchen table. The cooking supplies, including a two-burner stove that uses white gas, are stored either in the box, or in the two purple kitchen boxes. Generally, only one or two of us are in here at a time when cooking, as a little elbow room goes a long way.

Who wouldn’t want to cook in here – look at that counter space!

We each have our own mountain tent for sleeping. It’s always nice to have some personal space, and the multiple air mattresses, foam pads, and super warm sleeping bags make for a pretty comfortable evening. A couple of Christmas lights, some magazines, and it’s home sweet home for the next three weeks.

A super-warm down sleeping bag, plus Christmas lights, make for a comfortable tent.

Days are spent in our PistenBullys, collecting the GPS data of the ice sheet surface using survey-grade GPS systems that will be a critical piece of the ICESat-2 validation effort. We will spend about 300 kilometers around the 87.979 S line of latitude where the ICESat-2 data will be the densest. By comparing our measurements of the ice sheet elevation from the ground traverse, with the elevation measured by ICESat-2 on orbit, we will assess the quality of our on-orbit data and make any corrections necessary. We aim to cover our route in about three weeks and be back here at South Pole around mid-January. Happy New Year, and happy birthday Mom!

We’ll catch you in a couple of weeks!

-Tom and Kelly