May 25, 2024

Some 25 of us were up before 6 a.m. to head out on the bus from the hotel to Burlington International Airport to catch the C-130 aircraft, a military transport plane repurposed for NASA fieldwork, to begin our 7-hour flight to Pituffik.

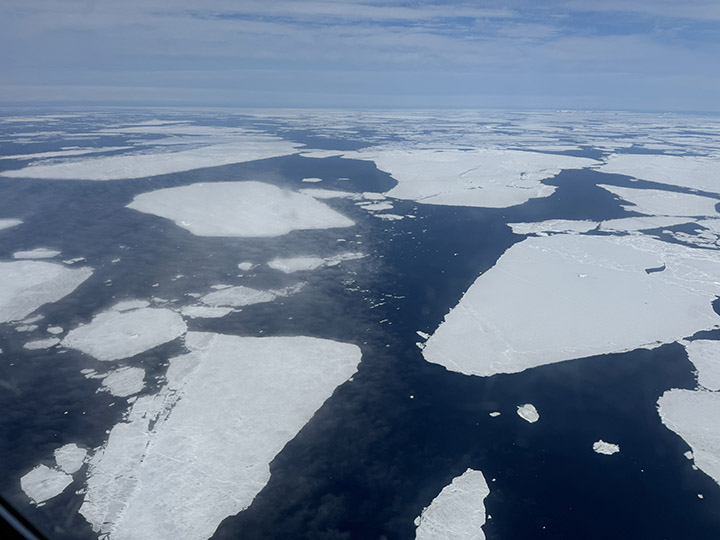

Several mountains of baggage, including scientific instruments and personal luggage, separate us from the less-well-heated economy cabin, which was probably reserved for graduate students, though we are far too collegial a group to check seat assignments. As we head north and east, the landscape out the window is vast, entirely gray-scale, and unforgiving: sea ice with streaks and patches of open water as far as one can see in every direction.

About halfway through the flight, we cross the Arctic Circle. Here the scene is often reduced to pure gray, and one cannot tell what is sea ice, snow, or cloud. This is the challenge we have long faced when attempting to interpret our remote sensing imagery; now, as an early gift of the expedition, I experience it directly.

May 26, 2024

The site is halfway between Washington and Moscow. Most or all of the buildings were prefabricated, brought here by ship in the summer, and mounted on stilts due to the permafrost. Some rough grasses are the only apparent vegetation.

In some ways, the base is well appointed. There is a sports center with an abundance of every conceivable exercise machine, also a tanning machine and a perpetual pool, a huge gym, and a yoga room. There is a recreation center with a movie theater, a lounge area with free apples, tea, and coffee, a game room that is more like an arcade with multiple video machines, and a craft center that has sewing machines (including a state-of-the-art Serger), rock cutting and polishing machines, computer graphics, and printers.

This is a remote place. The site is protected by a thousand kilometers of ice in nearly all directions, and the only ways to get here are by air or by boat for a couple of months of the year, when the sea is not frozen. With full daylight all day and “night,” the times-of-day are marked only by artificial clocks; the natural ones are essentially absent.

May 27, 2024

This was mostly a flight-planning day, getting ready for the first science flight of the campaign. It turned cold, windy, and snow fell today. This was more like what I expected but didn’t experience during the first two days. But now it is sunny again, around 6 p.m., and near-freezing, so there is still standing water on the roadways, and we are past the season when it is safe to walk on the ice-bound bay. The severe environment calls for some specific adaptations.

For example, the outer doors have latches that seal upward, so a bear pushing down on the handle will be unable to open the door. The walkways are made of open steel grids, so snow and mud will drip through. Boots are to be brushed before entering buildings, and plastic boot covers are provided in an effort to limit the amount of dirt that is tracked in.

I took a late-night walk. It’s daylight anyway, though overcast, windy, cold, and flurrying. Pretty much what I expected here.

The power went out twice today. Everything goes down, including the internet. I’m trying to keep everything charged, in case it happens again. Today’s weather represents “Condition Alpha” for storm warnings. That means just be on alert, in case things change. Condition Bravo means you cannot go outdoors without a buddy, or drive alone without a radio. Condition Charlie means you can’t walk out at all; there is a base taxi for urgent movement. Condition Delta: shelter in place.

The pipes are all above-ground because of the freeze-thaw cycle that would destroy the pipes. I guess they must be heated and insulated. They cross the road by going overhead.

Car and truck engines must be heated to avoid freezing and cracking. So, many of the buildings have power cords hanging out in front to run electric engine-block heaters. I didn’t take the last picture quite at midnight, but the scene doesn’t change much during the night.

I think I mentioned that it is mud season here. This is no joke. The place has a very industrial feel, and the only place to walk is on the mud roads. I’ve heard it will get worse as the mud deepens, and mosquitoes come out. Something to look forward to…

May 28, 2024

We had our first flight with the P3 today, and it was far better than I had expected. There was a rare case of cloud-free atmosphere over sea ice in one area north of Greenland where some buoys had been deployed, which allowed for both surface ice and aerosol characterization. Also, a nearly 3-hour run at ~500 feet captured aerosol properties over open water along the northern part of Baffin Bay. Among our objectives are learning the sources and properties of aerosols in the Arctic, their evolution as they age, and their impact on clouds. Others are especially interested in the properties of sea ice as it melts. So, this gives us a start on those objectives.

May 29, 2024

The wind is a force of nature. Today it has been blowing at something like 40 miles per hour, with gusts considerably higher. It literally takes your breath away—and this is just Condition Alpha.

Gusts create the sensation of blowing you away. All this under a relatively clear sky, bright sun, just a few clouds. It is somewhat other-worldly to one who has lived a life at lower latitudes. The temperature is only a few degrees below freezing, but the weather today gives new meaning to the term “wind chill.”

June 1, 2024

Today was an official day off, and in particular, a mental health day for the forecasters. Several of the military folks on the base arranged to take a group of us on a hike over the Greenland Ice Cap. There were 15 of us in five trucks. The trip involved a fair amount of driving on gravel roads in trucks—about half the time driving, half hiking – 5 hours total. The hike itself was about 5 or 6 miles, and we walked around and then on the glacier, though we never did find the Starbucks.

In addition to the stark beauty of the rock fields and ice, the sky is unlike anything we normally see at lower latitudes. The surface is cold, and the atmosphere is no colder (and sometimes is even warmer) than the surface, i.e., it is stably stratified—the “warm” air is already up, so there is not a lot of warm air rising and mixing that typically happens when the surface is heated directly by the Sun.

The glaciers have brought an enormous diversity of stones that litter the ground, and every piece of wood here was carried in from somewhere else. There are little clumps of vegetation, just enough to satisfy the appetites of musk oxen.

So far, I’ve seen Arctic fox (no pictures—they disappeared too quickly), musk ox in the distance, Arctic hare, and snow goose. No polar bears—and no complaints about that.

June 7, 2024

This evening I took a long walk out to the ice-bound pier… AND I SAW AN OTTER!!!

June 4, 2024

The Arctic foxes are molting. They were very cute when their coats were all white. Now they are losing their winter coats and turning brown. I did see a couple of full white coats, but was too slow to get a photo.

June 8, 2024

The project rented a van, and ten of us went off to climb the Dundas, that imposing rock feature not far from the base, though to get there without walking on thin ice (here the term is not merely a metaphor), one has to drive about 30 minutes over rocky and sometimes quite steep roads around the frozen bay.

The angle of repose is the angle a pile of dry sand (or salt) will make if you dump a bucket of it on the ground. It is generally steep (depends in part on the grain size and shape of the sand particles). Dundas is about 725 feet high; it appears to be the remnant of a glacial moraine—rock pushed here by an advancing ice sheet at least that high, that remained after the ice melted away. It is loose sand and rock, mostly gravel and cobble-sized. The climb up was, frankly, arduous, as there are not a lot of footholds.

The first part was steep enough that going on all fours was necessary in places, and the sand and small rocks would slip easily down the slope as one persevered upward. The final part was up a sheer rock wall that was graced, mercifully, with a sturdy rope. My pictures are lacking for the entire traverse, as all my effort went into the climb itself. I did stop part way up the rock wall to check my life insurance policy.

The view from the top was spectacular, but truthfully, there are so many great vistas in this rugged place that the main reward was accomplishing the ascent itself.

The way down was similarly fraught, except that below the rock wall, I had pretty much no choice but to slide down bit by bit—the loose surface material would give way at every step. So, on my back, lift up my rear, slide a few feet using my boots to stop, and repeat. There was some interesting vegetation on the slope—tiny plants and lichen, which I did photograph. I’m told that some of these plants can be hundreds of years old.

In the distance, we saw some dark spots that the binoculars suggested were seals. (Oh, yes—someone here said that my otter from last night was actually a ring seal; not sure that is authoritative, but…).

June 9, 2024

I agreed to join this afternoon’s walk up the edge of the Greenland Ice Sheet.

The slope is moderate by Dundas standards, and the path is completely snow-covered. The walk up is of course uphill, and a steady wind of 30–40 mph (the katabatic wind), with significantly higher gusts, blows off the ice. This guaranteed that however far we got up the ice sheet, we would certainly be able to make it down, either on foot or airborne.

There were pools of water within ice basins at the base. They look a beautiful shade of blue. We saw this in Alaska as well. I think it must be that ice either absorbs all the longer wavelengths, or it preferentially scatters blue, or both. The optics here are stunning, at least to me. Probably because they are unfamiliar.

One way painters provide a sense of distance in a painting is with “atmospherics,” that is, they increasingly blur the edges of more distant objects to account for light scattering by atmospheric gas and aerosols. Mountain climbers experience the opposite, in the thinner atmosphere, remote objects are sharper than they would in everyday experience, so more distant objects appear closer than they actually are. This is true here in Greenland as well, though we are not at a very high elevation along the coast. I expect the phenomenon in this case is due to a very clean atmosphere.

June 11, 2024

Today I got to fly on the P-3. Every satellite scientist should be required to take at least one such flight to see what the Earth is really like. We flew across northern Greenland and over sea ice. In the two weeks since the campaign deployment began, the depth of the sea ice, and the snow upon it, both decreased at those buoys (where it was measured), and, of course, most everywhere else as well.

A field campaign is a layered operation. Aircraft flight scientists build, run, and maintain the twenty or so instruments that measure particle composition, gas concentration, cloud properties, surface reflectivity, and upwelling and downwelling energy. They are awake by 4 a.m. to prepare their instruments for flight, worry about power supplies and calibration, then sit on the plane for six or seven hours, noting what they see from their measurements and out the window.

The number of leads (i.e., openings in the ice) has increased in places. We flew at high elevation to survey the area, measure the overall surface topography and reflectance, and sample aerosol layers aloft, then descended to 300 feet above the ice to capture aerosols emanating from the surface. The photos tell an accessible part of the story. The rest must be teased out of the data in the coming months and years. But my ride is over for now—there is an aerosol forecast due tomorrow.

June 12, 2024

It was flurrying this evening, and my walk carried me down toward the pier. But you might be pleased to know, I did not go all the way; several seals have now been seen on the ice at the pier. My otter or seal in the water was the first anyone saw, and although they say it is relatively rare for bears to go near the base, seals are their primary food. I figured, after a long winter hibernation, a bear might not count me as even a light snack, but in consideration that I had already booked my flight home, I turned around before getting very near the water’s edge.

June 14, 2024

I should say that the food here is okay. Better than I expected. Of course, in such circumstances, it pays to begin with low expectations: hardtack, pemmican, and beef jerky. The cafeteria serves a lot of beef and pork, but there is also chicken, a reasonable salad bar, excellent, fresh bread (the highlight in my opinion), always two of THE three kinds of fruit (apples, oranges, and bananas—so yes, they mix apples and oranges), and of course, Danish, at least in the morning.

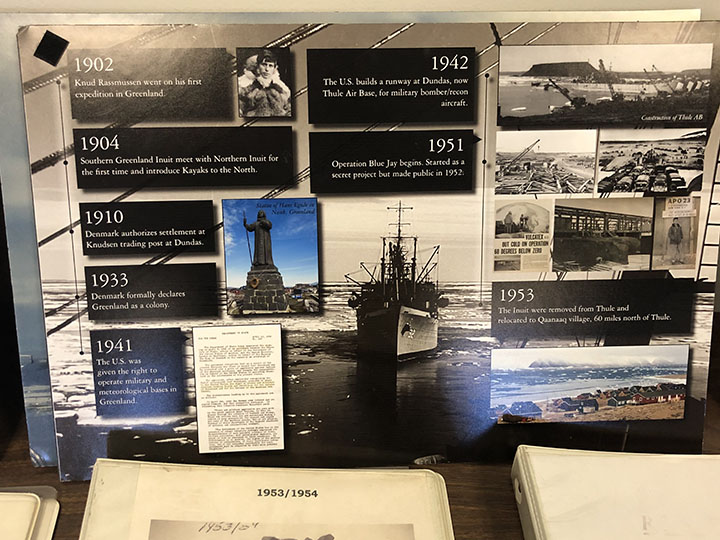

In the evening I took a walk, as usual, and ended up in one of the dozens of prefab buildings on the base, with the suggestive label “Heritage Hall.” The door was not locked, and the lights turned on as you entered each room. The place is a sort of museum, a repository for things discarded from the 1950s and 60s.

They have a computer punch-card machine, a vacuum-tube TV set, and a radar scope you will recognize from science-fiction movies. Also some notebooks with photos of the army’s Camp Tuto (now abandoned—only remnants of the airfield remain) and the presumptive city “Camp Century” they built into the ice in the 1950s. The walls flowed at glacial speed but ultimately collapsed.

Thule base was established in 1951, succeeding three waves of Inuit who inhabited the area, apparently beginning 4,500 years ago. The most recent came around 900 CE, met the Norse about 100 years later, and were moved to a new village 60 miles to the north in 1953. There is even a Life Magazine cover showing ships delivering material to the base in September 1952.

Ralph Kahn, an emeritus research scientist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center now at the Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics at the University of Colorado Boulder, spent three weeks at Pituffik Space Base in northern Greenland in the summer of 2024. He was one of dozens of scientists who participated in ARCSIX (Arctic Radiation-Cloud Aerosol-Surface Interaction Experiment), a NASA-sponsored field campaign that made detailed observations of clouds and atmospheric particles to better understand the processes that affect the seasonal melting of Arctic sea ice. These excerpts from his emails home to family provide a glimpse of what life was like on one of the world’s most northern scientific outposts in the world. Photos were taken by Kahn or Gary Banzinger, a NASA videographer who also participated in the campaign. Kahn, an atmospheric scientist, worked with colleagues to provide daily aerosol forecasts that were used to help plan flights.

By Alek Petty

A mix of old and new sea ice floating through the northern Beaufort Sea during one of the last days of the cruise that we observed sea ice.

After 65 Rosette casts, 59 XCTD probes, 61 Bongo tows (nets that collect zooplankton samples), 212 surface water profiles, 40 ocean drifters released, three buoys deployed, one buoy recovered, three deep sea moorings collected and redeployed, eight ice cores collected, and 27 scientists deployed and partially recovered, our expedition around the Beaufort Gyre is finally over! The cruise was a huge success, with virtually all instruments operating successfully. The only downer was the lack of sea ice and our inability to get out onto the ice after Ice Station 1. The lack of ice wasn’t actually a problem for most of the scientists onboard, as they were more focused on measuring the state of the ocean, with the lack of sea ice providing interesting, albeit worrying, context for their measurements compared to previous years.

Final Joint Ocean Ice Study 2016 cruise map (Sept. 22-Oct. 18, 2016)”. Courtesy of Chief Scientist Sarah Zimmermann.

As I said back in my first blog entry, one of the key objectives of the expedition was to produce an up-to-date assessment of the freshwater content of the Beaufort Gyre. Based on a preliminary analysis of the data collected on this cruise, my colleagues reckon the total freshwater content of the Gyre could be at a record high. A chemical analysis of the ocean surface suggests that sea ice melt contributed around 20 percent of the fresh water mixed up within the surface waters, compared to around 80 percent from Canadian and Russian rivers flowing into the Arctic. The sea ice contribution was thought to be neutral a few decades ago, but the ice is now melting more than it’s growing, as we clearly witnessed, causing an imbalance. The wind circulation is also important in driving the ocean circulation that sucks in fresher surface waters into the Gyre (see an earlier blog of mine for more details).

Why does this all matter? Well, some scientists posited that the Beaufort Gyre oscillates between periods of spinning up and sucking in freshwater, and spinning down and releasing fresh water. A kind of breathing, if you like. The Gyre has been spinning up and sucking in fresh water for a few decades now (2008 saw a big increase) and we keep waiting, with similarly bated breath, for this trend to reverse. If the Gyre does reverse (breathe out), the Arctic Ocean will likely dump a load of fresh water into the Atlantic Ocean (as we think it did in the 1970s), which could cause some big impacts on weather patterns across the Northern Hemisphere. We’re not expecting a scene out of The Day After Tomorrow, but we’re not entirely sure what could happen either.

Hacky sack on the helideck. You can spot me by the bright orange hat.

It will take scientists a while to pour through all the data collected on this cruise and place this year’s findings into context. We spent our last few days compiling reports to summarize and document the data collected (in between games of hacky sack on the helideck). I’ve taken a look at some atmospheric data since I got back, and it appears the Beaufort Sea region was experiencing really warm, maybe even record warm, air temperatures throughout October. The data collected this year could therefore offer us a glimpse of what might be a new normal for the Beaufort Gyre and other regions across the Arctic Ocean.

I wasn’t able to cover all the science that happened on the ship during this blog series, but I hope you got a flavor for some of our primary scientific activities and have a better understanding of why it is we keep coming back to profile the Beaufort Gyre. I’m not sure if I will be out again next year, but I’ll be sure to let you know if I do. Thanks for reading, and do get in touch if you have any questions!

The Joint Ocean Ice Study is a collaboration between the Department of Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) researchers with colleagues in the USA from Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI). The scientists from WHOI lead the Beaufort Gyre Exploration Project, which maintains the Beaufort Gyre Observing System as part of the Arctic Observing Network. In addition to WHOI and DFO, the 2016 participants (those on board plus those on shore) come from three Japanese, five American, and six Canadian universities and research laboratories. Annual sampling of set oceanographic stations and mooring re-deployments since 2003 aboard the CCGS Louis S St-Laurent have built a time-series of physical and chemical properties of seawater, phytoplankton, zooplankton, and ice observations reaching from shelf waters to 79N across the Beaufort Sea. More information can be found on the Fisheries and Oceans Canada website.

By Alek Petty

View from a helicopter of our ice breaker, the CCGS Louis S. St. Laurent, taken after Ice Station 1.

The sea ice didn’t last long. We continued the hunt for sea ice suitable enough for another ice station – hoping for something thicker and more stable than last time around. Unfortunately our search was fruitless. The Woods Hole team tried for a quick installation of one of their ice tethered profilers (ITPs) –an ocean surface water profiler- on a thick ice floe that was only around 164 feet (50 meters) in diameter, but the ice was too ridged and porous to be suitable and the operation was quickly abandoned. They instead resorted to deploying two of their ITPs directly into the ocean from the side of the ship (this is less stable than wedging the surface buoy component of the profiler into an ice floe, hence why they’re called ice tethered profilers). Our hopes of getting out onto the ice again quickly vanished.

We were soon back to cruising through the marginal ice edge, which was dominated by newly forming young grey ice with the occasional floe of older, thicker, ice that had survived the summer melt season. We are now back to swaying our way through the high seas – not the kind of scene most people associate with an Arctic expedition. It was with a sense of deep regret that our time within the ice ended with nearly two weeks of the expedition still to go. For me, the expedition just isn’t the same without the sound of ice breaking reverberating around the ship (we’re on an ice breaker after all!)

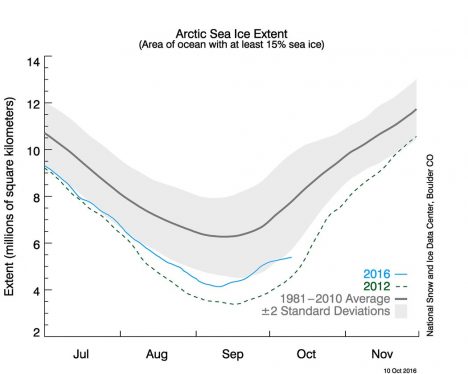

Arctic sea ice extent as of Oct. 10, 2016.

We got a small dose of Internet after leaving the ice (I’m struggling to cope without it!) and I managed to get access to the National Snow and Ice Data Center website, which showed how the Arctic sea ice re-freeze has been really slow this year (see the sea ice extent image above), coinciding with very warm temperatures over much of the Arctic, including the Beaufort Sea. We’ve experienced temperatures only slightly below freezing on this expedition, so my thermals have stayed packed away. In the Beaufort Sea, the ice edge is clearly not heading south at any real speed, although as the temperatures are expected to drop further through the coming weeks and months, a refreeze across the entire Beaufort Sea should be inevitable.

Scientist Adam Monier looks out over Arctic sea ice.

Despite the lack of sea ice (and my associated despondence), the science was still operating at maximum speed. We had a talk from Adam Monier, a French microbiologist from Exeter University (United Kingdom) who talked about his efforts, along with collaborators from Concordia University (Montreal, Canada), to increase our understanding of the microbial communities of the Arctic Ocean. According to Adam, around 90 percent of the global ocean’s biomass is microbial (a mass equivalent to roughly 240 billion elephants!) and this was seriously underestimated as of only a few decades ago. He showed some fascinating results demonstrating how phytoplankton (a micro algae) can cope, and even adapt, to fast changing environmental conditions, like sunlight and access to nutrients – some of which can be linked to the changing Arctic sea ice state. There is still a severe shortage of Arctic data, and this cruise is trying to help fill in those gaps. As phytoplankton are the foundation of the Arctic Ocean’s food webs, understanding how they respond to rapid changes in environmental conditions will be key to understanding how the entire Arctic ecosystem responds to declining sea ice and changes in the Arctic Ocean. The expedition has been a great way for me to learn about the latest developments in Arctic science, and to appreciate how interconnected our various fields of research are.

By Alek Petty

Working on thin Arctic sea ice.

After five days of cruising through open water, it was clear we had to change course and venture further north to find ice. The satellite imagery was showing ice above 76-77 degrees North (we were around 74 degrees North), and the ice edge didn’t seem to be drifting south at any real speed. After another few days voyage northwards, we thus finally found ourselves entering the Arctic sea ice pack. This wasn’t exactly a scene from the Titanic; the transition from water to ice was a gradual one, as the ice cover evolved from millimeters or centimeters of newly forming sea ice (nilas and grease ice), to thicker, consolidated ice floes (maybe a meter or two thick; 3.3 to 6.6 feet), which caused the ship to lurch and shake as it broke its way through.

Early stages of sea ice growth: nilas (top left), pancake ice (top right), young grey-white ice (bottom left) and first-year ice (bottom right). The top photos are courtesy of Jean Mensa.

Once we were well within the ice pack, the Woods Hole team was keen to get out onto the ice and deploy some buoys. This would be my chance to get out on the ice too, as I was helping lead efforts to collect ice thickness measurements and ice cores, to better understand the characteristics (like salinity, density and age) of this year’s Beaufort Sea ice pack. The microbial and microplastic scientists were keen to join in and collect their own ice cores, too, enabling them to take a deeper look at what else might be hiding within the ice.

The Woods Hole team leader flew out with the helicopter pilot early the next morning to hunt for thick ice, and seemed to find an ice floe thick and stable enough for us to work on. I joined them on the first science flight out a few hours later to set out our survey lines and coring sites, before our cargo was carried over and the rest of the team members joined us. It was soon apparent that the ice wasn’t as thick as we had hoped.

I drilled a few quick holes and the readings all came in at around half a meter, just above what might be considered safe to work on. Our polar bear guard, Leo, wasn’t too happy with the conditions either and soon found a few good sized holes and cracks circling us. We were under strict orders not to stray from the group and to test the ice for stability as we moved ahead. I’ve previously used data from satellites, planes, and sophisticated computer simulations to estimate the thickness of Arctic sea ice. Yesterday, I estimated ice thickness by hitting it with a stick.

Danger ice!

It wasn’t quite vertical limit, and the group rebuffed my idea of roping together for dramatic effect, but there were still a few hairy moments when the odd leg found its way through the ice. Despite the added element of danger, all operations completed successfully and we hitched a lift back to the ship later that afternoon with our ice cores in tow. The Woods Hole team was working until last light to get their buoys prepped and ready to drift off through the Arctic. It was a fun, adrenaline-filled day of science, but I’d prefer it if we could find some thicker ice to work on next time around.

By Alek Petty

My journey up to the ship went smoothly and I even had time to observe the Northern Lights (Aurora Borealis) in full bloom during our overnight layover in Yellowknife (in the Northwest Territories of Canada). The following day, a Canadian Coast Guard helicopter transferred us from Kugluktuk airport onto the ship, and after another day spent refueling and replenishing the boat, we were finally on our way to the Arctic Ocean.

The Northern Lights.

The Louis S. St. Laurent ice breaker.

I actually spent the first two days of our polar expedition sat out on deck, enjoying the sunshine and views over the Amundsen Gulf. In the distance I could just about make out the mouth of the Mackenzie River delta – a key outflow of fresh and mineral rich river runoff into the Arctic. This shelf sea region is rich in wildlife, including beluga whales and even narwhals. We looked out eagerly, but only spotted a couple of lowly seals in the distance. Maybe on our way back we’ll have more joy.

On Saturday morning, we emerged into the Arctic Ocean proper —the Beaufort Sea! — where conditions were a bit less serene. In fact, one of the consequences of the diminished Arctic sea ice cover over the past decades has been an increase in Arctic Ocean waviness, as the lack of sea ice enables winds to more effectively whip up the ocean. Arguably one of the most distressing impacts of climate change for us unhardened scientists.

Despite the continued lack of sea ice, the water sampling exercises have begun in earnest. At each research station (a virtual station if you will, we just stop at a predetermined location in the ocean) a large metal carousel with various water samplers attached —a rosette, as we call it— is released, profiling the water column as it sinks to the bottom of the ocean, before being hauled back up to the ship for analysis.

A rosette deployment.

There are around 50 stations in total that we plan on hitting during this expedition. The various scientists on board all have their own things their looking for in the water —plankton, bacteria, alkalinity, dissolved inorganic/organic carbon, micro-plastics (yep, they make it to the Arctic Ocean too), etc. You name it, we’re sampling it.

One of my tasks, along with Japanese scientist Seita Hoshino, is to profile the water column in-between theses stations using XCTD (eXpendable Conductivity Temperature and Density) probes. XCTDs provide a quick and cheap (well, about $800 per probe, so not that cheap) real-time analysis of the temperature and salinity of the water column while the ship is moving. I’ll try and show you an example profile in a later blog post.

We’re hoping to hit some ice soon, as for us ice observers there’s not a whole lot for us to get really excited about yet. It’s quite the contrast to the cold, icy conditions of my 2014 expedition thus far…