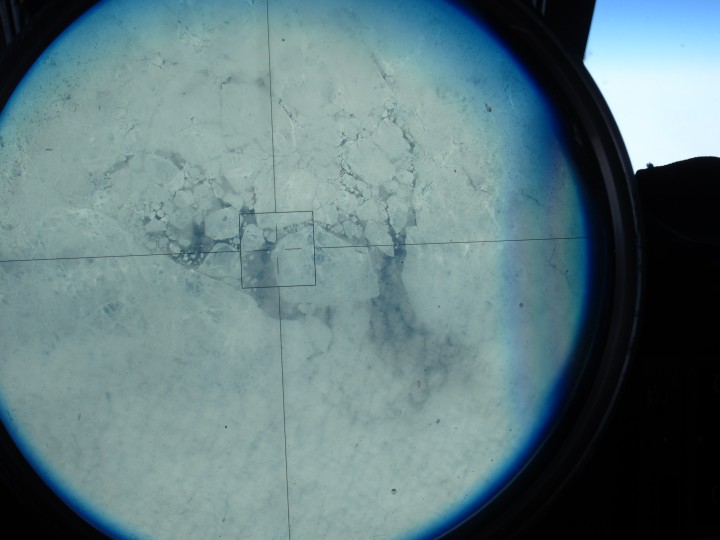

The North Pole! NASA pilot Tim Williams flew over the pole Wednesday afternoon. It was a cloudy day at 90 degrees north, as seen through the ER-2’s viewsight. (Credit: Tim Williams/NASA)

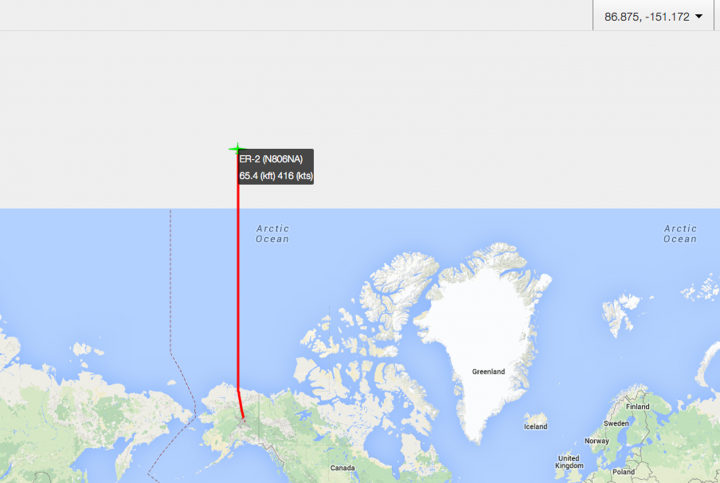

Fly north from Fairbanks and after a while, you’ll be off the map. Literally, as ER-2 pilot Tim Williams found out Thursday when he flew the NASA aircraft on a mission to the North Pole and back.

“At some point, the map’s not there,” he said at a post-flight debrief Thursday evening.

“Here be monsters” – or just map projection issues. Once the ER-2 got above about 89.5 degrees North, the pilot’s map didn’t cover it. Those of us tracking the plane from https://airbornescience.nasa.gov/tracker/ lost the map even earlier.

Williams flew due north along the 150 degrees west longitude line, carrying scientific instruments including MABEL, a laser altimeter that scientists are using to develop software for the upcoming ICESat-2 satellite mission. The goal for the pole-bound trip was to gather data over the spectrum of summer ice – from open water, to degrading ice, to thin ice, to multiyear ice, with some melt ponds on the way.

It was a smooth and cloudy trip up, Williams reported, and through breaks in the clouds he could see cracking ice below.

Sea ice, as seen through the ER-2’s viewsight, on the 150 degree latitude line north of Alaska. (Credit: Tim Williams/NASA)

“I expected it to be a lot more solid; it’s not,” he said. “It doesn’t look thick where I could see it.”

After about four hours in the air he reached the pole – 90 degrees latitude. His instincts were to look at the compass onboard, but it was “just a mess, it’s all over the place,” Williams said. At one point, his compass showed 180 degrees opposite from his navigation system.

On top of the world! Tim Williams piloted the ER-2 to the North Pole – it’s all south from here. (Credit: Tim Williams/NASA)

Still, he knew which way to go: “When you hit the pole, everything is to the south. So you just make a turn,” Williams said.

He rolled out, circling from the pole, until his navigation system gave him a heading. He found the 140 degree line, and flew back to Fairbanks – headed south.

Clouds blanketed much of MABEL’s potential flight routes over the Alaskan Arctic or southern glaciers on Monday, so the ER-2 aircraft stayed in the hangar at Fort Wainwright in Fairbanks, Alaska.

But the MABEL team was busy. They took advantage of a day on the ground by improving the instrument’s new camera. The goal is to take more images like the one below, to help scientists interpret the data from the airborne lidar instrument.

As the ER-2 aircraft traveled from Palmdale, California, to Fairbanks, Alaska, the camera on MABEL took this shot of wind turbines near Bakersfield, California. (Credit: NASA)

It’s the first week of the summer 2014 campaign for MABEL, or the Multiple Altimeter Beam Experimental Lidar, the ICESat-2 satellite’s airborne test instrument. MABEL measures the height of Earth below using lasers and photon-counting devices. This year, the team is using a new camera system to take snapshots of the land, ice and water in parallel with MABEL’s measurements.

The MABEL instrument is nestled snug in the nose cone of the high-altitude ER-2, which has a circular window in the base where the laser and the camera view the ground. To get access to MABEL and the camera, the crew propped up the nose and wheeled it away from the aircraft.

The ER-2 crew rolls the aircraft’s nose — containing MABEL — away from its body, so engineers could work on the instrument. (Credit: Kate Ramsayer/NASA)

The team then carefully slid the instrument out onto a cart, so that MABEL’s on-site engineer and programmer – Eugenia DeMarco and Dan Reed – could work on the camera and ensure the connections were sound.

MABEL engineer Eugenia DeMarco and programmer Dan Reed work on improving the new camera system for the instrument. (Credit: Kate Ramsayer/NASA)

When the camera was set to document the terrain from 65,000 feet, the team slid MABEL back to its spot and wheeled the aircraft’s nose back to the rest of its body. They connected the instrument to the plane’s electronics, sealed the plane back up, and are ready to go whenever the weather cooperates.

Luis Rios, with NASA’s ER-2 crew, checks the connections between the MABEL instrument and the aircraft. (Credit: Kate Ramsayer/NASA)

Very few people get to fly 65,000 feet above Alaska’s glaciers. And even fewer get to fly over ones they share a name with. But on Friday, as pilot Denis Steele flew NASA’s ER-2 aircraft from Palmdale, California, to Fairbanks, Alaska, he snapped a picture of the scenery below – including Steele Glacier in the southwestern corner of Canada’s Yukon territory.

From NASA’s ER-2 aircraft, pilot Denis Steele saw glaciers in southern Alaska and Canada — including the Steele Glacier, the horizontal feature in the center of the image, and the Donjek Glacier (lower right). (Credit: Denis Steele)

Steele and the ER-2 team, along with NASA scientists, engineers and others, are here in Fairbanks to fly a laser altimeter – MABEL, or Multiple Altimeter Beam Experimental Lidar – over melting summer sea ice, glaciers and more. It’s a campaign to see what these polar regions will look like with data from ICESat-2, once the satellite launches and starts collecting data about the height of Earth below. Gathering information now allows scientists to get a head start in developing the computer programs scientists will need to analyze ICESat-2’s raw data.

MABEL and other lidar instruments are flying on the ER-2, which provides a high-altitude perspective. In the next three weeks, the plan is to cover melting sea ice, glaciers, vegetation, lakes, and more.

Steele wasn’t the only one looking out of the plane windows on flights north. Kelly Brunt, a research scientist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, spotted a wildfire in Eastern Washington. The fire, burning in steep terrain, resembled an erupting volcano.

Over the weekend, the team settled into Fairbanks and a hangar at the U.S. Army’s Fort Wainwright, downloading data from the transit flight and ensuring the instruments are ready to fly when the weather allows. Cloudy skies over key sites means the ER-2 won’t fly today (Monday), but the team will check the weather tonight and see if it clears enough to fly the first science flight on Tuesday.

Want to follow MABEL and the ER-2? Check back here, and also check NASA’s flight tracker: http://airbornescience.nasa.gov/tracker/