April 24, 2015 — I believe in one of my first blog posts I mentioned that we were working in an area of high accumulation (snowfall) on the Greenland Ice Sheet. I would like to change that to an area of VERY HIGH accumulation! Actually Southeast Greenland does receive the largest amount of snowfall on the entire ice sheet. In previous years we have experienced storms dumping over a meter of snow. This year we had one of those storms bringing well over a meter of snow and then 3 hours after the first storm ended we got a second, bigger storm, pushing our 5 days snow total to nearly 3 meters of snow.

The amount of snow is best summed up by a dinner conversation in our cook tent where Olivia, being on the ice sheet for the first time, asked Clem, Josh and I, ice sheet veterans, what the biggest storm we had ever been in was like. We all responded, in unison,” this is the biggest storm we have ever been in!” While the weather was not particularly cold or windy, it just kept snowing. The low wind made it possible for us to continue science measurements through the storm in a special tent, with no floor, providing both shelter and access to the snow.

The storm hit on the day we were finishing up drilling. We drilled a 56 m borehole into the aquifer, reaching water around 19 m below the snow surface just as we expected. Drilling ice cores is a routine practice on the ice sheet and allows us to see the structure of the ice and measure the ice density; it is less dense near the surface and then compacts to ice at around 35 m in this region. Josh drilled the ice core using both a mechanical drill, called the sidewinder, in the top 19 m of dry firn and with an electrothermal drill in the water saturated firn below. Josh would drill about 1 m of core every 10 minutes and then Clem and I would weigh it, measure it, record ice layers, record the ice temperature and bag certain sections for Olivia’s hydrology measurements. Once the core was processed we took the remaining core to the kitchen tent to melt for our drinking water. (The more dense ice from deeper in the ice sheet produces more water than the less dense surface snow, so we are happy to use it for making water for the camp.)

While we were finishing the drilling Kip and Olivia were working out the kinks of using their equipment for the first time on an ice sheet. They worked through a few freezing issues and quickly had the first every water samples from the aquifer. They melted a piezometer into the ice sheet, inserted a tube and started pumping up water. We were all ecstatic to see the water gushing out of their tube and into their sample bottles.

As the hydrology sampling continued so did the storm. We had not received another resupply flight so we were running low on fuel, did not have a snowmobile or sled to move the drill to our next site and our additional team mates and measuring equipment had yet to arrive to complete more science. We knew we were already very delayed so we made the decision to postpone our seismic measurements until the fall. In the meantime the snow continued to fall!

By the third morning of the storm we were all sinking into the snow at least up to our thighs, if not our chest. Our tents were about 7 meters apart and it could take 5 minutes, and half your energy, to break trail between them. We often found it easiest to craw on the surface as opposed to walking. While the hydrology crew collected samples the rest of us dug out camp. We dug about every 2 hours. Even during the night we would have to get out and dig. In the end Josh moved into a tent with Kip and Clem, a tight fit, but more comfortable than digging out his smaller mountain tent all night. We also moved our fuel and generators into the cook tent and let our science gear get buried in its cargo line, marked with tall poles at either end, until the end of the storm. This reduced the area we had to shovel.

As the snow continued to fall, the winds stayed low. We were thankful for the low winds but knew after the storm the katabatic winds, outflow of cold air that gravitationally flows off the ice sheet, would kick up with a vengeance. On April 20th we woke up to light snow and no winds. The storm was over so we dug out all the cargo creating snow piles over our heads. Now we needed a Helo to bring in more science gear, and fuel, so we could keep working. The surface conditions were so soft that we could no longer operate a snowmobile even if we had one. At that point we knew we would only get one site completed this season because we really couldn’t move.

The calm was short lived. By the afternoon the Katabatic started with the furry we expected. The winds increased to 30 knots very quickly. Over the next 3 days the winds blew and moved all the snow around again. We were digging out our tent almost every hour. All we were doing was digging. Digging out the tents, digging the snow out of our pockets, goggles, gloves, everywhere! We were tired! We made a decision to end the season once a Helo could get in since we had completed most of the measurements. Today, April 23, we finally got a Helo and all flew back to Kulusuk for a nice shower and warm meal. Tomorrow we will day trip back to remove our camp and, hopefully, let Anatoly make the first every electromagnetic resonance measurement on the aquifer.

Hello! This is Olivia and I’ll be writing about the hydrology work we are doing this year on the Greenland ice sheet. A few years back some scientists on our team discovered liquid water inside the ice sheet. They partnered with us to study the water in greater depth.

We think that the snow melts at the surface, percolates down through the snow and firn, and pools inside the ice. The water fills up the air space between the ice crystals, creating an aquifer inside the ice sheet that we think behaves similarly to aquifers found on land. The hydrology that we are doing this season is basically a “groundwater” hydrology study, except that in this case it is an “ice-sheet-water” hydrology study. We will try to test our ideas about how the aquifer behaves and understand what that means for the ice sheet and sea level rise more broadly.

To answer these questions, we will collect measurements of how deep the water is and how much pressure it has to determine where the water is entering and exiting the aquifer. We will test how quickly the water travels through the firn and also collect water samples. The chemistry of the water will tell us information about how long the water has been inside the ice sheet. All of this information will give us a much better idea of how the aquifer is filling up, and where the water is going, and how quickly it moves. This kind of information is important for understanding how ice sheet melt relates to sea level rise. If the aquifer is storing water for long periods of time, than it may have less of an immediate impact on sea level rise. However, what happens if it fills up and suddenly drains quickly? Or maybe it is constantly draining?

To make our measurements and collect our samples, we had to do a lot of work to modify traditional groundwater hydrology tools and instruments to work at very cold temperatures. Groundwater hydrologists often use piezometers, long pipes that have a small opening at the bottom to let water in, to access the aquifer they are investigating. To install a piezometer into the ground, you can pound it in. To install our piezometer into the ice, we have developed a piezometer with a heated tip that can melt through the hard ice layers.

Another challenge we face is that many of the samples we collect cannot freeze, and yet we expect the temperature at our field site to often be below freezing. When we collect these samples, we completely fill the sample bottle so there is no air space in the bottle. We do this so that we can analyze gasses that are dissolved in the water back in the lab. If these samples froze, the water would expand and break the bottle, ruining the sample. To prevent these samples from freezing, we have modified several coolers to be extra-insulated and to have special heaters inside them.

It has been quite the learning experience to take all of our groundwater hydrology work to such a different environment! But this is part of what makes the science exciting. We get to try something that has never been done before.

The past week has presented many successes and challenges for the team in the field. The weather has been a huge issue, not only in helicopter load delays, but also in being able to perform the science needed. The team has been hit with over 2 meters of snow and up to 40-knot winds in the time they’ve been there. This even includes covering Josh’s mountain tent entirely with snow, though he has now moved into a larger Arctic Oven tent joining Clem and Kip. It has slowed them down, but not stopped them in the slightest. They have persevered through the storm and fully completed the drilling, hydrology, and radar work at the first site. Another meter of snow is expected throughout the rest of today (April 19) and tomorrow. Our team plans on continuing to dig out and make measurements no matter what Mother Nature throws at us next.

After many long days of waiting, we got an update yesterday that our helicopters would be down until April 16. We have had bad luck so far with delays – mechanical difficulties and bad weather. The team’s morale sunk to an all-time low with this news. We had been anxiously awaiting a call each day to tell us we were going to fly.

This morning, April 10, we got the news that we would probably not be flying because the helicopter was still not ready to go. Disappointed, we went on about our daily activities including going to the store and exploring town. When we got back, we heard exciting news. Fin, our pilot, had called saying he was on his way and to get ready for two flights today! The team sprang into action, furiously packing bags, driving to the airport, and getting camp and science gear into the final loads.

The Bell 212 helicopter landed around 2:30 p.m. We began to pack all of our things in when the pilot announced we could only take 650 kilos instead of the initial weight we had thought of 800 kilos. We had already stripped our science and camp gear down to the bare bones to fit the first weight limit. With this new cut, we had to take out even more gear within minutes. Although we had to cut down the first flight, the rest will be put on the second flight. Josh, Olivia, and Clem left successfully landed on the ice sheet.

The helicopter made good time, returning for the second flight around 4:30 pm. This time, they upped the weight limit to 900 kilos from 650 kilos for the first flight. Instead of having a weight problem, we were quickly maxing out on volume. At the end, we successfully got most of our science, camp gear, and food in plus Lora and Kip! We are so excited that the initial team has set up camp and is ready for the first night out in the field. I will go in on one of the next few flights.

There are two sling loads planned for the next two flights to take in the drill and the two snowmobiles plus more science gear. Anatoly will arrive soon on April 15 and Nick on April 20. We are slowly but surely getting all of our gear and scientists into the field.

Today (March 8, 2015) marks our tenth day in Kulusuk. We are now officially three days late getting into the field. This is pretty typical for field work in this area but we are still a bit restless, ready to get to our final destination and start taking our measurements.

Our standard day in Kulusuk starts with breakfast at the hotel. After breakfast we hear from the helicopter pilots as to whether we have a chance of flying. There is one Air Greenland helicopter right now for this region that is responsible for commercial traffic, taking supplies to the nearby villages and charter flights, like ours. Our first delays started on Sunday and Monday when the helicopter was grounded needing to have some standard maintenance. While we were disappointed to not fly, it really didn’t matter because we were in the biggest storm yet with 40-knot winds. No flying no matter what! The storm and maintenance aligning was actually quite lucky. We tinkered with some final gear, caught up on email, and on Monday night settled in for a movie at the hotel. Towards the end of the movie we heard a strange rattling noise. It was a small earthquake! We emailed Nick and he sent us some great information from the seismometers near by showing the quake which was a 1.9 on the Richter scale. Too bad we didn’t have our seismic equipment deployed or we would have even more data.

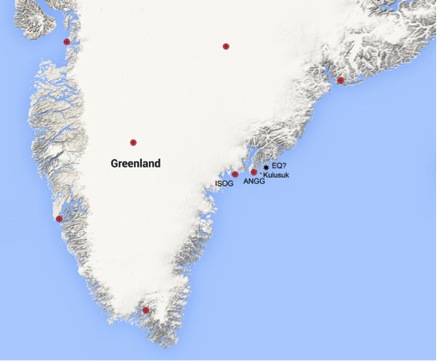

A map of the Danish Seismological Network (red dots), showing the stations in the area and the black star the approximate location of the Earthquake.

The waveforms from stations near Kulusuk. The event rolled through around 9:11 pm local time at Tasiilaq. It was a high frequency earthquake!

On Tuesday we woke to blue skies and great views of the surrounding mountains. I packed up my final bag before I even came up to breakfast expecting to fly. At breakfast the call from the pilot brought very bad news. The maintenance on the helicopter detected another issue that required a new part. The helo is now grounded and expected to be for a while. There is another smaller helo on its way to Kulusuk but it will not arrive until the end of the week. We have adjusted all of our loads so that we can use either Helo, whichever is ready first and, hopefully, we can use both to make up some time.

We spent the rest of the beautiful day on Tuesday testing our hydrology equipment and a new ice core drill on a nearby frozen lake. In the evening, the clear skies allowed us to see the Northern lights for the first time on this trip, and for many on the team, for the first time ever. We made the best of the day considering we would have preferred to be in the field. Now we will just wait for both a weather window and a working helicopter. It just started snowing outside again so we may be here for a while longer. Fingers Crossed.