For students who want to take atmospheric science as literally as possible, it doesn’t get much better than flying in a NASA aircraft.

Each year, the Student Airborne Research Program (SARP) invites a team of rising college seniors to Armstrong Flight Research Center in Southern California to conduct research aboard NASA’s airborne science fleet. Each aircraft is equipped with instruments for land, ocean, and atmospheric research–enabling sample collection and imaging over the Earth’s surface. After operating the instruments in-flight, participants are then able to use the resulting data for their own individual research projects.

…as soon as they recover from the air sickness, of course.

Jacob Schenthal, who graduated from Vanderbilt University in 2021, was drawn to the NASA SARP program for its emphasis on independent, field-based research and multidisciplinary scientific teams. McKenna Price-Patak, a 2021 Tulane University grad, felt it was a rare opportunity for an undergraduate student to be responsible for an entire research project: from data collection to analysis and project development.

“I’ve always had interests in a variety of fields within Earth science, which is why I was excited about the multidisciplinary aspect of SARP,” Price-Patak said.

Both Schenthal and Price-Patak were placed with Dr. Donald Blake, conducting air sampling aboard the aircraft to study atmospheric pollution.

Dr. Blake is kind of a big deal in the atmospheric science community. An atmospheric chemist at UC Irvine, Blake is half of the eponymous Rowland-Blake Group: the research lab whose other namesake, the late Dr. F. Sherwood Rowland, won a Nobel Prize in chemistry for identifying compounds responsible for Earth’s ozone hole. Today, Blake continues the lab’s work as a leading expert on the impacts of atmospheric chemistry and air pollution on human health, and has conducted NASA-sponsored airborne research for over 30 years.

“Dr. Blake is a phenomenal mentor and really helped me find a newfound interest in air quality research–which intersects directly with climate change and environmental justice: two of my other passions,” Schenthal said. As Price-Patak put it, “Don takes a genuine interest in each member of his group and their success. When my project took a last minute detour and had to be redone days before final presentations, Don sat with me on Zoom for hours a day helping me recover and create a project I was proud of.”

Both Schenthal and Price-Patak were accepted into the SARP program in 2020. Unable to make the flights that year due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the program had to take a different approach. For the first time in SARP’s history, participants received air quality testing canisters in the mail to remotely collect initial data points.

“Although the program during summer 2020 was remote, it was exciting to take air samples to help measure emission impacts of the COVID-19 lockdowns,” Schenthal said.

“The way the program pivoted to a virtual environment was incredible,” Price-Patak said. “While we would’ve loved to be in person, we still had so much support from our research groups and mentors so we could successfully complete our projects in the short time frame.”

Schenthal’s project, titled Investigating Xylene and Toluene in Disadvantaged Communities Downwind of LAX, blended NASA’s airborne science data within an environmental justice framework. He examined how xylene and toluene–two airborne compounds that damage the nervous system with chronic exposure–are more common in disadvantaged communities near and around Los Angeles International Airport (LAX). Schenthal found that Inglewood, a predominantly Black and low-income community, experienced exposure levels for both compounds at 50 times the background level. Additionally, his project results indicated the compounds acted as tracers, meaning hundreds of other pollutants are also potentially travelling from LAX throughout these communities.

Price-Patak’s project, Dimethyl Sulfide (DMS) in the Imperial Valley and its impact on Sulfate Aerosol Loading, used data collected on SARP flights from 2014 to 2019 to locate sources of inland DMS. DMS is typically released from plankton in the ocean, and can turn into sulfate aerosols which can cause respiratory illness. Her research indicated there may be inland sources of DMS producing up to 10% of the sulfate aerosols in the Imperial Valley, an important agricultural region east of Los Angeles.

More than a year later, they got their chance to make the flight. In December 2021, fully-vaccinated participants from the 2020 and 2021 teams were finally able to take their projects airborne. Over the course of a week, the team participated in multiple flights over southern California aboard a DC-8 aircraft, taking samples adding to the program’s extensive record of air quality data.

By the end of the program, Price-Patak and Schenthal were able to rack up a combined 27 hours of flight time–and even experienced sitting in the cockpit for low approaches around Long Beach harbor!

According to Price-Patak, the value of the program comes not only from the work itself, but from the opportunity to connect with other early career scientists.

“Through SARP, I developed a new interest in atmospheric chemistry and connected with other students who have gone on to work as consultants with business firms, pursue PhDs, and everything else in between. Not only is the opportunity to conduct research through the program incredible, but the flights are truly a once in a lifetime experience. I would recommend any undergrad student with a STEM background to apply!”

“SARP has been an incredible experience, both personally and professionally. For me, it allowed me to explore my interest in air quality and environmental justice–all while engaging in field research and my independent research project,” Schenthal added.

Now, Schenthal and Price-Patak credit SARP in helping their careers take off–with both program alumni now working with NASA SERVIR at the University of Alabama in Huntsville (UAH).

A collaboration between NASA and USAID, SERVIR works with organizations around the world to design and implement satellite-based services supporting climate adaptation and natural resource management. Schenthal is the Regional Science Associate for SERVIR’s Mekong hub, while Price-Patak is a graduate research assistant for SERVIR-Hindu Kush-Himalaya while enrolled in UAH’s Master’s program in Earth science. And yes–both are still involved in air quality research. The application for SARP 2022 closes January 26th, and can be found here. Don’t hesitate to apply–and be prepared to pack your dramamine!

Update: The R/V Endeavor returned from sea on Aug. 6, concluding the fieldwork component of the 2014 SABOR experiment.

As mentioned in the previous blog (“A Vast Ocean Teeming with Life”) ending this cruise is not an easy thing to do. Especially if you experienced the majesty of the crystalline blue water in the open ocean as well as the magnificence of the wildlife surrounding it for the very first time. I am currently coursing my third year as a PhD student in the Electrical Engineering Department of The City College of New York (CCNY). I work as a research assistant for a small department in the Optical Remote Sensing Lab called Coastal and Oceanic waters group. We may look like a group of cool guys going out for fishing (as it seems on the left side of the picture), however, we are a team who works hand to hand together (depicted on the right side of the picture … why does the right side always seem right?)

“Cool guys” aka Coastal and Oceanic waters group, members of the ORS Lab at The City College of New York (CCNY). Courtesy of Lynne Butler

My research consists of using polarization properties developed as the light field propagates through the water body and use this information to characterize and retrieve water constituents and inherent optical properties (also called IOP’s) from polarimetric measurements. The basic idea is that as light propagates through the water it experiences significant attenuation due to absorption by water and suspended/dissolved matter as well as scattering by water and suspended particulates. These effects, both absorption and scattering, result in signal degradation of the radiance captured by sensors in our instruments. The additional information obtained when using polarization properties of underwater light propagation can provide a better understanding of this propagation and methods for improving image quality and increase underwater visibility … wait! (at this point you may be asking yourself).

So how can this have a real contribution to the goals and objectives pursuit by the SABOR (Ship-Aircraft Bio-Optical Research Campaign) cruise? Well, the answer could be very simple. The ocean is too big and in-situ measurements are too expensive to cover the entire water mass on Earth. Having this in mind, it is very clear that we need to adopt another cost-effective approach and that is the reason why we use satellite observations to account for many changes that take place in the ocean and coastal waters. Satellites provide very useful information when properly calibrated. As you may already know, sensors deteriorate over time and satellites go out of commission. However, polarization features are preserved even when the sensors may have experienced normal degradation and knowledge of this features can contribute in the development of future technologies to be used in satellites when more accurate and reliable information is to be acquired. Some living and manmade objects in water have partially polarized surfaces, whose properties can be advantageous in the context of target camouflage or, conversely, for easier detection. Such is the case for underwater polarimetric images taken to detect harmful algal blooms (red tides) or to assess the health of marine life and coral reefs which are of significant scientific and technical interest.

The main challenge faced by these images is that of improving (increasing) the visibility for ecosystems near and beyond the mesophotic depth zone. Data collected in the form of images, videos and radiance was acquired using a green-band full-Stokes polarimetric video camera and measurements of each Stokes vector components were collected as a function of the Sun’s azimuth angles. These measurements are then compared with satellite observations and model using a radiative transfer code for the atmosphere-ocean system combined with the simple imaging algorithm. The main purpose of this task is to validate satellite observations and develop algorithms that improve and correct these observations when needed.

It always looks like I am playing video games but in order to have very accurate information it is advisable to position the instrument at a certain orientation with respect to the Sun’s azimuth angle. The instrument depicted here is called Polarimeter and as Robert Foster suggested in his blog it has a very boring name, so we are still in search of a cool code name after someone suggested (unsuccessfully, and I am glad for this) to call this instrument Carlos. A real issue came across when they were thinking to put Carlos in the water … an idea that I didn’t share. The polarimeter, let’s forget about Carlos for a moment, is a set of Hyperspectral Radiance sensors with polarizers oriented in the vertical, horizontal and 45° from a reference axis. This sensors can capture light coming from any point in the water body thanks to a combination of a step motor which can be programed to stop in any sequence of angles in the range of 0 – 360° (from vertically up to vertically down) and a pair of thrusters (or propellers) which can rotate in the azimuthal direction (both clockwise and counter-clockwise). This scenario allows for vitually a 3-D range of hyperspectral measurements. Pretty cool, huh? The set of bouys at each corner allows us to have a very stable system and prevent the instrument from going very deep down in the case that cables and safety line get cut.

When things go like they do in the left image, we always have to do the right thing. Courtesy of crew members and Ivona Cetinic

Very far from what most of us have probably experienced in a cruise or fishing trip, the ocean is not always calm. In our twenty plus days in the ship, we came across a system which was playing very rough against the R/V Endeavor. Fortunately for us, this cruise was under the supervision of very talented and experienced people. I am not talking only about the captain, but also his outstanding crew members, chief scientist and marine technician. Although we have some minor difficulties (… you should know by now that sea water and electronics will never be good friends) we fixed them as soon as the storm was gone. It is not that Robert and I are playing as firefighters rescuing a dispaired kitten from a tall tree.

I want to end my vision of this field campaign with a summary of the awesome marine wildlife that somehow approach to us to say hello, some species more shy than others, to this group of scientists which were part of NASA-SABOR. As depicted in the picture (left-to-right and top-to-bottom), one of the first appearences was that of a seagull. It doesn’t look that shy since it preferred posing for us on top of the Polarimetric Lidar (owned and operated by scientist from NRL). Very intelligent creature this particular one, the others were just swimming in the waters and preparing to be a snack for a hungry shark as depicted in the image in the top center. Another interesting character which showed up near the surface was previously mentioned by Matthew Brown from Oregon State University in the previous blog post and it was a species of blueish salp with very long tentacles. The next creature is a very friendly dolphin which pretended racing us so we could take very amazing pictures. Dolphins always so adorable, appearing in pods and jumping out of the water around the research vessel or just posing underwater in front of the polarimeter! The last living character was a very shy sperm whale. Always keeping the distance but letting us know it was present leaping out of the water at most 300 feet from the ship!

These past three weeks in the R/V Endeavor had been very amazing although intense. Waking up and knowing that you are far from home, your friends and family may sound questionable but understanding that you are in front of one the most wonderful and powerful sources of life is a priceless experience not all of us can witness. That is why I am writting this blog and I hope you have enjoyed reading all our blogs and could have a taste of what is like being in the sea for three weeks!

August 5, 2014

Three weeks at sea is a long time for someone who has never been out of sight of shore. My greatest impression during my time out here is the one I first had when we first set out: the ocean is really, really big! I realize that probably sounds too obvious to be worth mentioning, but the sheer vastness of the ocean is hard to overstate. Standing on the deck, turning 360 degrees and seeing nothing but smooth, blue water as far as the horizon, it’s hard not to be struck by how empty it all appears.

The SABOR science party on the deck of the R/V Endeavor. Front row: Wayne Slade (Sequoia Scientific), Deric Gray (Naval Research Laboratory); second row: Kimberly Halsey (Oregon State University), Alex Gilerson (City College of New York), Nicole Poulton (Bigelow Laboratory for Ocean Sciences), Matthew Brown (Oregon State University), Lynne Butler (University of Rhode Island), Nerissa Fisher (Oregon State University), Ali Chase (University of Maine), Nicole Stockley (WET Labs), Robert Foster (The City College of New York), Coutrney Kearney (Naval Research Laboratory); back row: Carlos Carrizo (City College of New York), Allen Milligan (Oregon State University), Jason Graff (Oregon State University), Ivona Cetinić (University of Maine). Credit: NASA SABOR/Wayne Slade, Sequoia Scientific

Of course, that’s not true at all. The ocean, far from being empty, is teeming with life. Most of it is too small for us to see with the naked eye, but it’s there all the same and it affects each and every one of us even if we’ve never been to the sea in our lives. Phytoplankton, the microscopic algae that live in the sunlit regions of the ocean, not only provide much of the oxygen we breath, they also play an important role in managing the earth’s climate through their roles in uptaking CO2 from the atmosphere and cycling nutrients like nitrogen and sulfur through the ecosystem.

A big part of what our group does is trying to understand how different aspects of the ocean environment (light, nutrients, grazing pressure) affect the ability of the phytoplankton to photosynthesize and grow. One way we do this is through a piece of equipment called a fluorometer, which can give us an indication of how efficiently algae are absorbing photons from the sun and turning their energy into carbon. It works by hitting them with a large amount of light, then measuring what percentage gets released back after getting absorbed. A simple enough technique in principle but one that can tell us all sorts of things, from the size of the molecular antennas the algae use to harvest light to the degree that electrons can be shared between different reaction centers in the chloroplast.

Another technique we use which is pretty cool (or rather, hot) is the use of radioactive isotope as tracers to measure carbon uptake. On the Endeavor that activity takes place in the Rad Van, which is named for radiation and not, unfortunately, for how radical it is. By allowing algae to photosynthesize in the presence of CO2 formed with the carbon isotope 14C, we are able to track how much the carbon is taken up under a variety of different conditions.

Well, three weeks have come and gone and we put into port tomorrow. It will be nice to be back on land, but I will miss the excitement of the ocean. Today, we got a going away surprise in the form of a pod of dolphins that came near our boat and splashed around for awhile. In addition, the water around the ship was filled with a species of salp, gelatinous creatures which kind of look like sea jellies, that was bioluminescent and gave off a brilliant blue light. It was almost like the ocean knew we were leaving and decided to give us a show to send us off.

After just over a full week at sea, we have found the rhythm of our life and work routines. We collect water with the CTD rosette, deploy instruments over the side of the ship, work in the lab, eat, and sleep. That might sound like a lot of work and no play, but we do manage to have fun while we work (think lab dance party while filtering water samples). We’ve also taken time to observe the vast blue around us from the upper deck of the ship, where we recently watched a gorgeous sunset. No green flash sightings yet but I continue to hold out, hoping to see this optical phenomenon – a green flash of light that can sometimes be seen just before the sun disappears below the horizon.

Left: View of the sunset from the top deck. Right: Deck operations just after sunset, which includes deploying two instrument packages that measure a variety of optical parameters, and the CTD rosette, which collects water samples from different depths. Credit: Ali Chase

Several days ago we crossed into the Sargasso Sea, which is an area of very clear blue water due to low amounts of phytoplankton and dissolved matter which absorb light and make the water in some areas, such as coastal regions, a greener color. But here the water is an amazing deep blue color, which is the color of ocean water when there is not much there besides the water itself. One life form that is prevalent is a seaweed called Sargassum, which we frequently see floating by.

The very blue water of the Sargasso Sea, with a few floating pieces of Sargassum. Each piece is roughly the size of dinner plate, for scale. Credit: Ali Chase

Speaking of things that absorb light in the ocean, much of the work we do in the “wet lab” is related to the absorption and scattering of light by different particles in the ocean. This optical oceanography work allows us to measure the way light interacts with particles, in particular phytoplankton, which absorb and scatter light differently depending on the types and amounts of phytoplankton present. Throughout this cruise we are collecting water continuously using a system involving a boom that extends over the side of the ship with a hose hanging from it into the water. A pump on deck constantly brings water from approximately three meters depth through the hose and into the wet lab, where it then flows through several instruments and provides us with constant information about the optical properties of whatever is in the water.

But, the ocean is a massive place, something that we are very much reminded of while working at sea with no land to be seen in any direction. Even sampling the water continuously during this three-week trip will just give us a small snap shot of ocean conditions. This is where satellites come into play, as they can provide a much broader spatial view of the world’s oceans. However, work in the field is necessary to “ground-truth” what the satellites tell us, to be sure that such expansive information can be accurately related to what is present in the ocean. During this research cruise we will pass through several types of water, such as the warm/salty/fewer phytoplankton water like we see here in the Sargasso Sea, versus cooler/nutrient rich/lots of phytoplankton water in coastal areas such as the Gulf of Maine. Understanding the differences between these regions can be useful for interpreting satellite information about phytoplankton and their role in the earth’s carbon cycle.

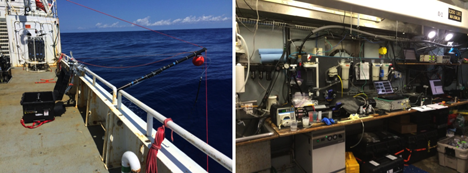

Left: The flow-through intake system; the hose hanging from the end of the black boom sucks up water continuously using the pump located in the black box on deck. Right: The wet lab in all its glory – the tubing with the water pumped from outside can be seen running up near the ceiling; it then flows through several instruments positioned both in the sink and on the bench top. Credit: Ali Chase

A couple of days ago a storm system passed over us, and the winds came up to about 30 knots. With winds that high, waves crash onto the deck and it is unsafe to deploy instruments over the side of the ship, so our work was put on hold for a day. I spent some time on the bridge (where the ship’s captain and crew navigate from) and watched the bow of Endeavor ride the waves like a roller coaster. Every now and then the bow came down against a big wave and an impressive spray of ocean water was sent flying, with water reaching as far as the windshield of the bridge where we were watching!

To document our work and life on board we have been putting GoPro cameras on everything, including hard hats and instruments that are deployed over the side of the ship. Recently a GoPro went for a ride on the “Polarimeter”, an instrument that measures the polarization state of light, which Robert mentioned in the previous blog post. While the GoPro was underwater, a big group of dolphins came to say hi, and the GoPro caught it on camera – very cool! We also lowered Styrofoam cups down with the CTD to a depth of 1,000 meters, where the pressure compresses them, along with any writing or pictures that have been drawn on. We sent down a bunch of cups from a school group that had visited the University of Maine’s Darling Marine Center, and we added a few that we decorated ourselves for souvenirs to bring home.

Left: A selfie I took while wearing the GoPro on my hardhat. Credit: Ali Chase; Right: Dolphins near the Polarimeter deployed with a GoPro attached. Credit: Wayne Slade

Styrofoam cups that were attached to the CTD and lowered to 1,000 meters, where the pressure compresses them (top = before, bottom = after; box of tea shown for scale). Credit: Ali Chase

I feel very fortunate to be included in this adventure at sea with such a great group of scientists and crew. I am constantly learning about the ocean and how we understand it as oceanographers, as well as all of the techniques and logistics that go into the collection of quality data. It is certainly humbling to be out on the ocean with nothing but blue all around, and I am reminded of why I am drawn to this field of study and how much of our planet is covered in this blue expanse. Thank you for taking the time to read our blog and I hope you’ve enjoyed this glimpse into our life and work at sea!

Ali Chase is a graduate student in oceanography at the University of Maine’s School of Marine Sciences.

Text by Robert Foster

City College of New York – CUNY

Here we are ending the 4th full day aboard the R/V Endeavor, and I can hardly believe it! Time really does fly when you’re having fun! Amid the rush of running cables, installing sensors, learning new and exciting science and making new friends, I couldn’t be happier. I am a 3rd year Ph.D student in the Electrical Engineering department of The City College of New York, and through extremely fortunate circumstance I found myself working in the Optical Remote Sensing Lab of NOAA-CREST.

Life aboard the R/V Endeavor is both exhilarating and exhausting! During our safety briefing I jumped into an immersion “Gumby” suit for the first time, giving my colleagues a good laugh as I tried to close the face flap with my lobster claw gloves.

I’m trying on the immersion suit for the first time and posing “mannequin-style” for the safety briefing Friday morning. Photo courtesy of Ivona Cetinic, University of Maine

Although we’re currently 18 miles off the shore of New Hampshire, we’ve already had several visitors!

On Saturday morning we spotted a pod of whales in the distance. They were too far away to photograph, but we could clearly make out their sprays and tailfins when they dove.

And the dolphins! This was the best part. Just a couple hours after leaving port on Friday the entire science team was on deck learning how to deploy the CTD when a pod of dolphins started leaping out of the water not 20 feet from the ship! It was almost as if they wanted to see us off on our journey! We managed to snap some really fantastic photos.

Dolphins jumping out of the water to see us off! Photo courtesy of Ivona Cetinic, University of Maine

Slightly more numerous than dolphins are the tiny phytoplankton which provide us with so much of the oxygen we breathe. Inside Endeavor’s main lab is an amazing instrument that can actually take pictures of these microscopic creatures and count them! Since one of SABOR’s primary science goals is to quantify how much carbon is being converted into oxygen by marine life, it is vital that we know exactly what species are present and in what concentrations.

Of course it’s impossible for the R/V Endeavor to be everywhere at once, so we must rely heavily on satellite observations. Current sensors such as MODIS (Moderate-Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer) aboard the Aqua satellite and VIIRS (Visible-Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite) aboard the Suomi NPP platform are designed to observe the ocean and atmosphere. Although they do it quite well in a general sense, there is still too much uncertainty to make absolute assessments of climate change and carbon cycling.

When we as humans look at an object, what is it that we’re actually seeing? (No, it’s not a philosophical question!) We see color and brightness. Seems sufficient, doesn’t it? But it turns out that there is actually another hidden property of light that we can’t see with our eyes, and it’s called polarization.

So if we can’t see the polarization of light, why do we care about it? Why is it a major focus of SABOR? The answer is because it’s becoming more and more difficult to increase the accuracy of satellite measurements using color and brightness alone. By incorporating polarization into our measurements, we are opening up a whole new dimension of information that was previously inaccessible. Our laboratory at the City College of New York is studying the way light becomes polarized in various conditions both above and below the surface of the ocean.

The first of the two instruments that we designed at City College is called HyperSAS-Pol. It is designed to automatically look at a fixed angle relative to the sun, regardless of the direction the ship is facing. HyperSAS-Pol measures both the polarization of sky light, and also light coming from the ocean.

I’m setting up HyperSAS-Pol on the bow tower of the R/V Endeavor. Photo courtesy of Alex Gilerson, City College of New York

Our second instrument floats on the surface of the ocean and measures the polarization of light underwater. We can rotate the instrument by using propellers that are attached to its arms. The sensors themselves are attached to a stepper motor which can look up or down in the water. With these two motions we can measure polarized light in any direction. By the way, this instrument doesn’t have an awesome code name like HyperSAS. We just call it the polarimeter… pretty boring name, I know. Maybe you can think of a better one? Post a comment!

While we are taking measurements on the R/V Endeavor, a plane will be crossing our path several times with a sensor capable of measuring polarization, as well as a LIDAR. During their test flight on Sunday afternoon we were able to watch the plane corkscrew down from the clouds to circle the ship! Too cool. They even took a picture of us!

The NASA Langley plane circling the R/V Endeavor on Sunday afternoon. Photo courtesy of Wayne Slade, Sequoia Scientific

Between the combined efforts of everyone onboard the R/V Endeavor and in the sky, we will be able to trace the complete path of polarized light coming from the sun, down through the atmosphere, into the water, interacting with all the little sea critters and finally emerging back into space to be captured by one of NASA’s Earth Observing satellites. If successful, our work here will be instrumental in the design of next generation satellites, such as the PACE mission.

We have one final visitor who is here in spirit, and his scientific value is without doubt. He makes sure that no light gets reflected off the white buoys and contaminates our underwater sensors. He is a childhood friend of mine, but I’m sure that you’ve met him before too!