The VISIONS-2 team got an early gift this year. Like an overstuffed stocking, our cardboard box for “red tag” items (items that protect the payload during testing, but which must be removed for proper operation during flight) is full to the brim. This means that at last, our testing is complete, and we can proceed to the launch window.

The Kings Bay Christmas party was a wonderful way to celebrate this milestone, and to get into the holiday spirit, with a huge gathering of everyone in Ny-Ålesund, including former employees, friends, and Kings Bay staff who flew up from the mainland. Kings Bay even flew in some catering staff so that the Kings Bay cooks could enjoy the party as well. It was quite the event. Everyone dressed up, and there was food and drinks and dancing, including a unique “Ny-Ålesund IPA” brewed specially for the town by Svalbard Bryggeri. We were also treated to a great auroral display that night, which whetted our appetites for the launch window.

After the party, a day off, and then we performed a dress rehearsal on Monday, which went very smoothly. We are now entering the launch window, which runs from 8 AM to just after noon local, from Dec 4-19. Each day we will elevate the rocket launchers, perform tests to make sure everything is ready technically, and then wait for the cusp and its crimson aurora to move to intercept our trajectory. To start at 8 AM, we have to be “on station” at 3 AM, to provide time for checking out all the rocket systems and preparing for a possible launch.

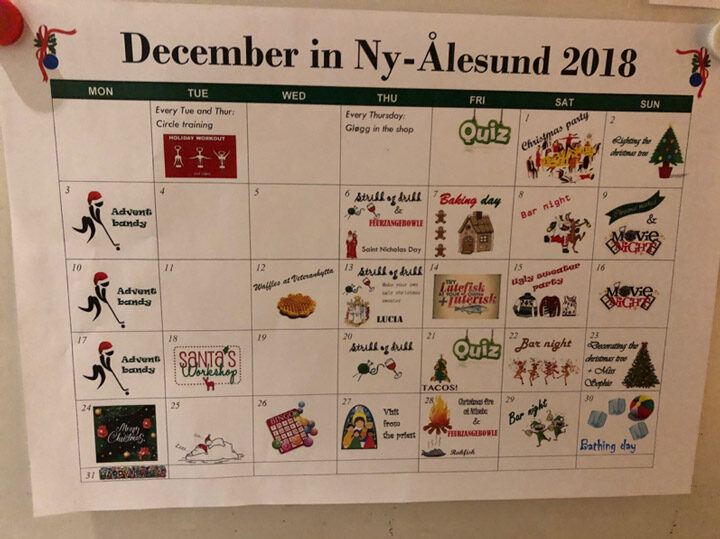

While we wait, we are experiencing the vibrant social life of the community of Ny-Ålesund. Between the Kings Bay staff, the Norwegian Polar Institute researchers, and researchers from many other countries, there is always something going on, from group dog walking (with rifles, just in case), to lectures on science or history, to “quiz night”. On other nights we have enjoyed nighttime photography excursions, to capture the aurora, often from outside the city limits (with a Norwegian guide and rifle, just in case), dog sledding around the town, movie night in the brand new “Kongsfjordhallen” (concert hall), hockey in the gym, or just a quiet night of billiards or foosball.

The community, though small and tight-knit, is extremely welcoming and inclusive, and we have been embraced at every turn. Sometimes it is tough to enjoy these activities and still be awake for the 3 AM “station call” but it is worth it – we have enjoyed so much hospitality here and it makes the long polar night infinitely more welcoming.

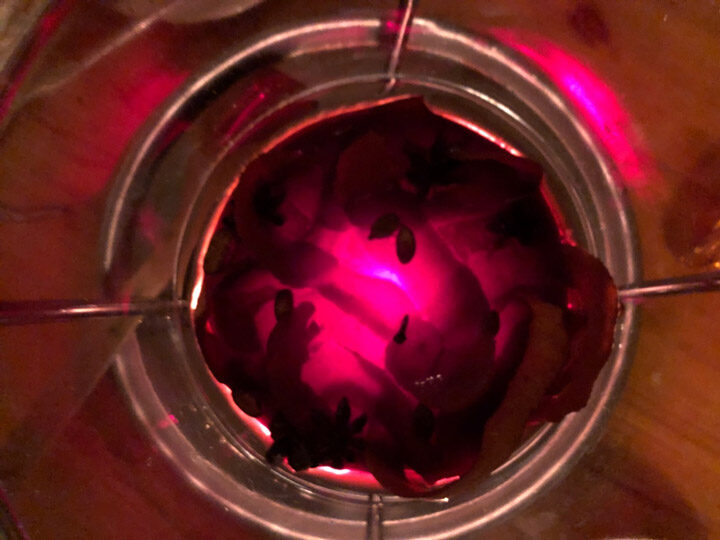

One of the most pleasant social activities (apart from karaoke night) is the weekly tradition of strikk øg drikk. This is the weekly gathering for “knitting and drinking”, where people bring their yarn and patterns and their drinks and snacks, to gather in the cozy couches of the Polar Hotel. Sometimes there is more knitting, other times, more drinking, but it is a good way to connect with everyone. There is even a group project to knit a “cozy” for the metal flagpole. It’s about halfway complete (only needs another 8 or 9 meters). As a special holiday treat, we enjoyed a taste of “Feuerzangenbowle”. With the lights down, and Christmas music playing, it felt like being transported to a quieter, slower time, the darkness lit only by the flames from the rum as it melted the sugar cone, and the room filled with the scent of the hot spiced wine.

Refreshed and re-energized by the welcome of our Ny-Ålesund colleagues, we are ready to launch.

“Isbjørn!”

That’s the word you never want to hear in Ny Ålesund. Stealthy hunters, polar bears (“ice bears”) are used to sneaking up on the seals that come ashore on Svalbard. They will stalk their prey, drawing ever closer and waiting patiently, until they can leap and dispatch their meal with a quick blow from their massive paws or a crushing bite. They rarely attack humans, and rarely come into town, especially in winter, but they are also well known for stalking humans. And with a top speed close to forty miles per hour, if they get within a hundred yards, there’s not much you can do if you are caught out on the ice with one. For this reason, anyone leaving the protected area of town must go, preferably in a group, with a loaded rifle. Shooting the bears is a last resort, because they are a protected species, with only 25,000 left in the world, and only approximately 3000 of those living on Svalbard. Your best hope is to scare the bear with a signal gun, a flare, or rifle shot aimed to miss. For the seals, their only hope is to reach the water. And even there, the bears can follow.

The sign at the edge of Ny-Ålesund reminding residents to carry a loaded rifle when leaving the town, and to unload the rifle when returning. Credit: Superchilum, CC-BY-3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Like the isbjørn, we are ambush hunters. Our prey are atmospheric fountains, jets of gas being shot into space under the impact of the cusp aurora. These fountains are strongest when the solar wind gusts above the gentle breeze that is normal for solar minimum, and when the solar wind’s magnetic field is oriented perfectly to unlock the Earth’s magnetic vault, like a key with wards of million-degree plasma and a shaft millions of kilometers long. The aurora that drives these fountains comes with at most an hour’s warning, radioed to us by the DSCOVR spacecraft, our “space weather buoy” balanced at the Lagrange pointbetween the Earth and the Sun. Until we get that signal, we lay in wait, ready, on a hair trigger, sneaking up on the aurora, taking care not to make any sudden movements, but prepared to hit the target.

Aurora over Ny-Ålesund. Credit: Ahmed Ghalib

When DSCOVR tells us that a solar wind gust is coming, we move into high alert, but cautiously, carefully, checking each step before settling in to the next, our eyes always on our target – a successful launch. There are 78 steps between the first scent of our prey and the final pounce. We may do them all in one motion, smoothly, or we may move forward a bit, then pause, wanting to entice the aurora into view, then start again. We will repeat this dance many times in the coming days. The surface winds are just as much our concern as the solar wind. If the solar wind gusts turn out to be too weak, or if the terrestrial surface winds pick up while we wait, we will have to reset, and wait for our chance to start again. In this way, we are just like the isbjørntrying to stay downwind of the seal, vulnerable to every change in the wind direction. The rockets are unguided, and to counter the effects of a wind that would blow them off course, we have to swing the massive launchers to a different heading. Our eyes and ears in this endeavor are the weather balloons, launched every 30 minutes so that we can correct our trajectory and fly straight and true towards the heart of the aurora.

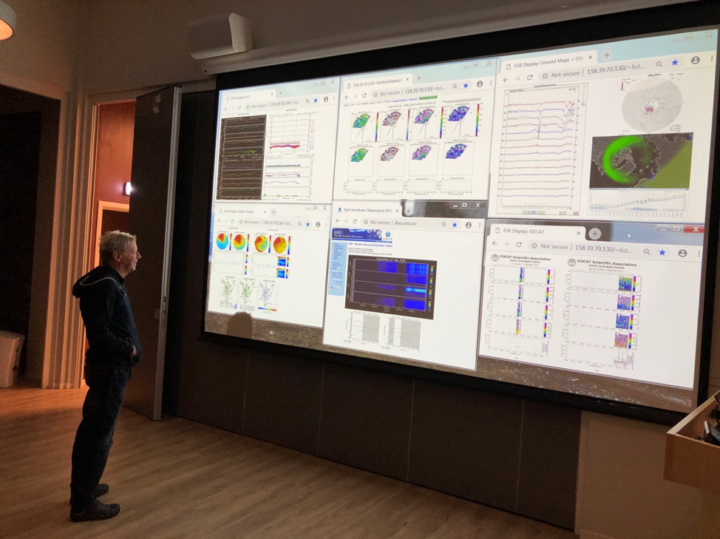

VISIONS-2 co-investigator Jim Hecht studies “the wall of science” which we use to display data that shows auroral conditions and forecasts. Credit: Doug Rowland

When the moment is right, we launch.

Paulo Uribe stands in front of the VISIONS-2 35.040 payload on the launch rail, during boxing (the styrofoam box allows us to regulate the rocket’s temperature so it doesn’t get too cold while we are waiting to launch) and rigging of umbilicals, liquid nitrogen and dry nitrogen lines, fiber optic lines, etc. so that we can control and test the payload up until the moment of launch. This is a new launcher designed by Wallops Flight Facility called the Mobile Medium Launcher (MML), and it is specifically designed to be large enough to launch our three-stage vehicles and yet easily transportable to remote field sites. Foreground: Paulo Uribe. Background, from left to right: Glenn Maxfield, Logan Wright, Hans Arne Eilertsen, Rusty Laman, Eric Taylor, Jorge Camacho. Credit: Doug Rowland

Doug Rowland, VISIONS-2 principal investigator, stands next to the 35.039 payload on its launch rail before completion of boxing. Credit: Paulo Uribe

Even then, it is never a sure thing. The aurora is slippery. Elusive. At launch it may be brilliant, dancing, daring us to come closer. But our rockets, though ultimately speedy, are massive, and take some time to get up to speed and reach their goal. In that brief time, just two to five minutes, the aurora may step aside, like a toreador flashing its brilliant red (630.0 nm) cape. Or it may fade, like a mirage.

Full moon over the 35.039 payload in its final GPS test before going to the launch pad. Credit: NASA

Or we may strike true, into the heart of an atmospheric fountain. If we do, we will have ten short minutes to luxuriate in the heated oxygen and hydrogen that sprays out into space, never to return. If we do, our neutral atom imaging cameras will be busy, building our grainy and blurry picture of the fountain as we fly through, over, and around it, taking its measure from all angles. If we do, our auroral camera will precisely document the nature of the aurora that is activating the fountain – its intensity, its temperature, and the height at which it is being generated. We believe that intense, lower-temperature auroras, that deposit their energies at higher altitudes (200 km) are more effective at driving fountains than hotter auroras that strike deep into the thicker atmosphere near 120 km. Our simultaneous pictures of the atmospheric fountain and the aurora will test this idea. Meanwhile, our other instruments will be listening, probing, sampling the gas, taking its scent as it were, to explore the details of how the fountain is generated.

Many times the aurora will evade us. But we are patient. And we have all the tools we need to wait for just the right moment to strike. We have cameras to track the aurora, to see the footprints of the energy that streams down the magnetic cusp from the solar wind. Powerful radars in Longyearbyen and Pykkivibaer to sense its beating heart. The DSCOVR spacecraft to warn of us its approach. But ultimately, we have to take a chance. We have to go, or not. Three years and more of work come down to 78 steps. And one pounce.

The air in Ny-Ålesund is thick with memory. There are no trees here, marking the years with their rings, only the endlessly accreted layers of ice in the glaciers. Most of the long history of Ny-Ålesund is written only in the rocks and the snow, an enigma that only slowly yields to the Rosetta stones of ice cores, rock drills, and mass spectrometers.

Aurora and moonlight over a Ny-Ålesund gravesite. Credit: Chris Pirner

But this is also a human place. In the last hundred years many have visited, many have lived, and some remain, in their final rest. Photographs hang near the foosball table, showing residents from a different time, resplendent in formal attire as they dine at tables set out on the snow, celebrating the return of the Sun. The styles change, but there is one constant — the spirit of adventure, of an impulse to explore; to live at the edge of the world and to go beyond. The same spirit that moves us and brings us here for our mission.

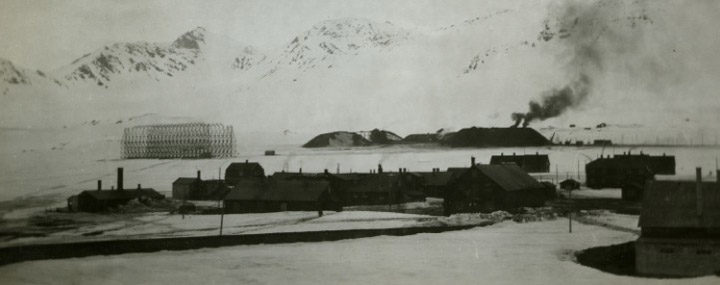

The Ny-Ålesund museum celebrates the lives of the coal miners and their families who first made this place their home one hundred years ago. They came for the rich coal seams lining the Kongsfjord — rich but dangerous. The nearly vertical seams tend to trap deadly methane gas, and many miners were lost in a series of explosions and accidents. Their spirits live on here — they and their families made this place. They carved it out of the tundra and rock, built the harbor and the houses and the airport. Without them there would be no town here, no research, and no rockets. We fly in honor of them and their courage, to make a living in this place, far from home.

Ny-Ålesund, 1928 – In the foreground you can see the town, and in the background, the mines and airship. Between 1916 and 1963, 82 coal miners lost their lives due to the dangerous conditions in the mine, including the buildup of deadly methane gas that was prone to explode. Now the mines are closed, and the town is focused on scientific research. Credit: Svalbard Museum

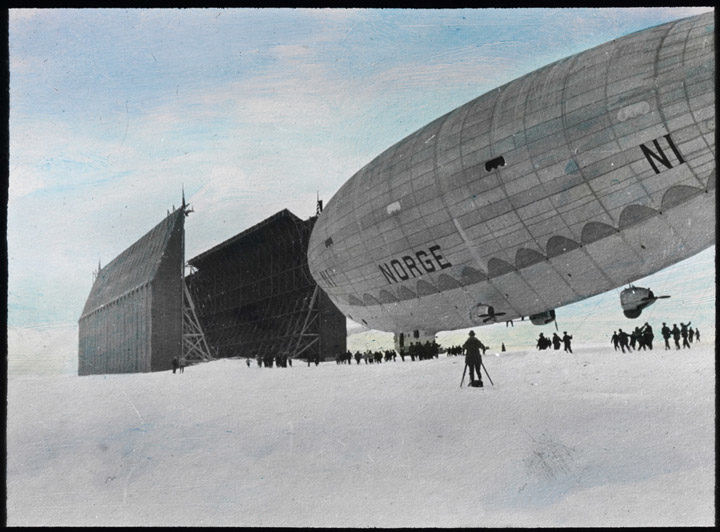

The polar explorers of the early 20th century recognized the value of Ny-Ålesund as a base, for the same reasons we come here — the safe harbor, the mild climate, and the solid land, last before the sea ice over the Pole. Umberto Nobile and Roald Amundsen and their crews took flight from Ny-Ålesund in May 1926, in the airship Norge. This zeppelin was the first vessel of any kind to reach the North Pole, and is celebrated here with many photographs. It is memorialized in the name of the Zeppelinobservatoriet, the high-altitude atmospheric monitoring station on Zeppelinfjellet, the mountain that rises 556 meters above town. While the Norgewas successful, the sister ship Italia, captained by Nobile in 1928 met a tragic end. On its return from the pole, it crashed into the ice north of Svalbard. Though many were rescued, 17 crew and rescuers died in the attempt, including Amundsen, whose plane crashed at sea as he flew to help. We fly to celebrate these airmen, and their thirst for knowledge and exploration.

The airship Norge, captained by Roald Amundsen and Umberto Nobile, as it prepared for launch from Ny-Ålesund on its way for the first overflight of the North Pole in May 1926. Its sister ship Italia crashed in May 1928 on its return from the Pole, with 17 fatalities among crew and rescuers, including Roald Amundsen who had flown his plane to help in the rescue. Credit: Nasjonalbiblioteket, CC-BY-2.0, via WikiMedia Commons

The researchers and Kings Bay staff who come here to work and live, some for months, and some for years, keep this town and all its facilities running. They work long hours each day and pour their hearts and spirits into Ny-Ålesund to make it a warm place. A place of community and curiosity. A place where you are just as likely to spend Friday night at a scientific lecture or watching a chess match as at a karaoke party or playing “bandy” which is like indoor hockey. Many of them go months or longer without seeing family, and have only the occasional trip home to break the long months of winter night. Nonetheless, they are professional, cheerful, and inclusive, making us feel welcome and at home. They worked to build the second launch pad that we need for our mission, laboring to bring the concrete and the rebar and the tools that could only be used for a brief warm period in the summer when the permafrost had thawed sufficiently. They worked to give us a beautiful Thanksgiving meal which was a welcome taste of home. They work every day to keep us warm, well fed, and safe, and to support our mission. The watchman, who patrols for polar bears, the electrician, who keeps the power plant and heat running, the technical manager and the reception staff who keep the hotel, dorms, and logistics running smoothly. The kitchen staff who work seven days a week to provide for us. All are here because they choose it — no one these days is born in Ny-Ålesund. We are all visitors here. But these long-term residents make the rest of us short-timers feel like we belong. We fly in thankfulness for their support and their welcome.

Thanksgiving dinner, which we enjoyed Saturday, Nov. 24. The Kings Bay staff pulled off an amazing and heart-warming meal, with all the American favorites – mashed potatoes, sweet potatoes (which the Norwegians were sure was meant for dessert). Glenn Maxfield, from the NSROC crew, coordinated to make sure the turkeys were in the sea shipment that left several months ago, in order to be ready for this meal. NASA family and friends also provided many of the recipes, which made it feel like home. Foreground, from left: Mark Frese, Norman Morris, Tim Wilson. Credit: NASA

Members of the receiving and telemetry team share a meal with some of the instrument team at the Kroa restaurant in Longyearbyen. Clockwise from left: Jim Clemmons, Joe Sherwood, Joe Kujawski, Nygel Meece, Jason McLain, Andrew Muender, Corbin Williams, Bob Swift, Zack Long, Andy Carlton, Ryan Charnock, Devon Raley. Credit: NASA

Our team shares the spirit of the men and women who have called Ny-Ålesund their home before us. We come from all over, to this place, in the spirit of adventure. We are far from home, too, and we are living at the extremes to accomplish our goals. We come from NASA, from Andøya, from Oslo, from Bergen, from Longyearbyen, from Canada, from our university and industry partners. We bring that same sense of community and drive to achieve that those before us have brought since the first NASA sounding rockets were launched here in 1997, and back to Ny-Ålesund’s founding in 1917. We fly to honor the sacrifices that we each have made, and the dedication we all feel to each other, in our three-year journey from project inception to field campaign.

Some of the payload and instrument team members, in front of the world’s northernmost train. From left: Chris Pirner, Ted Gass, Mark Frese, Tim Wilson, Norman Morris, Eric Taylor, Nate Empson, Logan Wright, Frank Waters, Jorge Camacho, Ahmed Ghalib, Doug Rowland, Mike Southward, Paulo Uribe. Credit: Chris Pirner

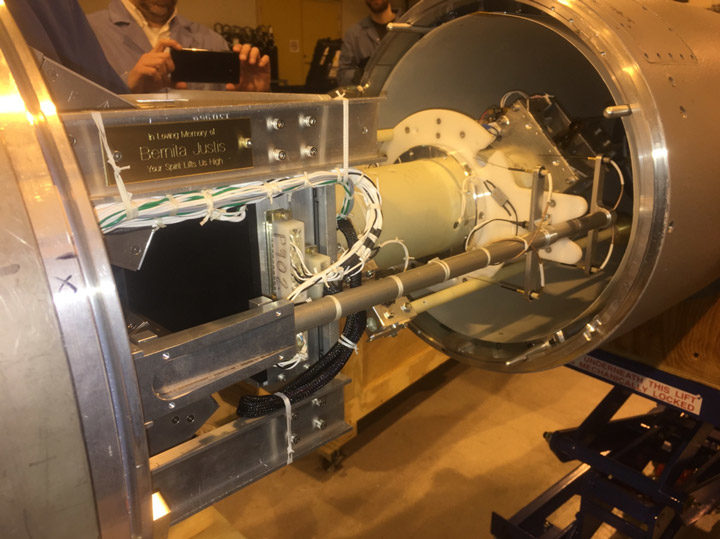

But there are those who could not be with us for this journey. Even in the midst of our joy, we have lost loved ones. Kelly Pham Nguyen, Alvaro Uribe, John Rowland, and Bernita Justis. We fly in their memory, as their spirits lift us high.

The memorial plaque for Bernita Justis. Both VISIONS-2 payloads carry this plaque, to honor her memory and the 31 years she dedicated to building and launching sounding rockets all over the world. Bernita passed this summer, in the middle of integrating the payloads for the Grand Challenge missions. Even in her last moments, she was hardworking, dedicated, cheerful, and positive. We fly in her memory. Credit: Doug Rowland

Our launch window opens in ten days – December 4. Each day brings us closer to being ready, as we continue the routine of testing and preparations. These are the same steps that we run through wherever we launch our rocket missions, but Ny-Ålesund has its own special atmosphere. Here, without the regular rising and setting of the Sun to bring a sense of duration, the long winter nights can seem timeless. We mark the days instead by our work shifts, blessedly interrupted by common meals warmly prepared by our Kings Bay colleagues at the Servicebygget, where everyone in the town eats together.

The cafeteria at the Servicebygget. All residents eat three meals a day here, as part of the “Velferden” system that encourages people to gather and share community, especially important during the long polar night. Credit: Doug Rowland

Meals are different here. There are no cellphones at the tables. This is because the village of Ny Ålesund, and a 20 km radius around it, is in a radio quiet zone — no cellular, WiFi, or Bluetooth. The quiet zone is designed to protect exquisitely sensitive radio antennas that are listening to distant quasars, one of many experiments ongoing at this scientific oasis. The meals are not quiet, however. People are focused on each other; on the food and conversation. Most meals have varieties of fish and potatoes, but there is also delicious homemade bread, fresh fruit (in high demand) and fresh vegetables. There’s always a smörgåsbord of cheese, meat, and relishes of various kinds, and cookies, pudding, or mousse for dessert. Every weekday, we have three meals together, and on the weekends two, with Saturday dinner a special “dress-up” event, with candlelight, when one can bring wine or beer to share.

In between the meals, we walk. A lot. The town has roads and plank walkways, laid down to protect the pristine tundra. Ny-Ålesund takes its stewardship of the environment seriously. There is no litter in the street, and it is forbidden to walk on the bare tundra, to protect the delicate ecosystem. There are few vehicles, mainly only for service and cargo handling. A few of the residents get by on bikes, but mostly people walk. The roads are typically covered in ice, so we wear spikes on our boots. For the first week or two, before the spikes, many of us were slipping, sliding, and falling, but with the spikes the roads are very manageable.

Walking down the “main street” of Ny-Ålesund. Reflective vests are a must, as most traffic is by foot, but there are service vehicles that need to use the roads as well. Credit: Doug Rowland

Though there is no sunlight (except a brief twilight glow at noon, and even that is fading as we approach the solstice), there is often enough light from the town and from the Moon, which is currently full and in the sky 24 hours a day. As we approach the launch window, the new moon will arrive, and remain below the horizon most of the day, letting us use our sensitive cameras to capture the faint aurora, and making the polar nights even darker. Usually one can make out the surrounding mountains and glaciers, and the calm waters of the Kongsfjord. There is even an occasional iceberg calved into the fjord, and they stand out white against the dark waters.

Besides the moon, our other constant companion is the wind. Most days there is anything from a fresh breeze to stiff wind, up to 35 mph (56 kph). Though the air temperature is in the teens (-5 C), the wind cuts through all but the warmest clothing. We are walking upwards of 1.25 miles (2 km) a day in this wind. The walk is another time for community, or at least commiseration, and it is also a time to enjoy the austere beauty of the landscape, the aurora, the moonlight on the water, and even the intense beam of the research LIDAR used here to study the atmosphere, flaring into the sky like a pillar of green flame.

The research station uses a green LIDAR to study the atmosphere – it is intense and striking against the background of a starry night. From left to right: Paulo Uribe, Long Nguyen. Credit: Chris Pirner

At one end of the walk is the payload assembly building, where we are testing the rocket payloads and science instruments. Sven, the harbormaster, has graciously offered his garage for the testing of the payloads, and the accommodations are luxurious compared to some other remote sites we have visited. Picture a large warehouse, sixty feet (15 meters) on a side, with a thirty-foot peaked roof. Spread about the floor are workbenches, packing crates repurposed as equipment racks, shipping containers, and the payloads themselves. A large roll-up door lets the trailers in and out, as well as the occasional icy gust.

Part of the payload team performing a “sequence test” of the “35.040” payload, one of two that we will launch as part of VISIONS-2. The Sequence test is the final end-to-end test of the rocket payload, in as flight-like a configuration as possible, where we verify that all the automatic timer-based events are activated when expected. From left to right: Eric Taylor, Koby Kraft, Mark Frese, Jorge Camacho, Ahmed Ghalib. Credit: Doug Rowland

At the other end, our dormitories, the Kongsbutikken (general store), gym, Ny-Ålesund museum, and Servicebygget (mess hall and rec center). All the buildings are unlocked, both for convenience, but also for safety in case a polar bear visits the town. In each building, we remove our boots and wear slippers or indoor shoes, to keep from tracking in the ice and snow (or scratching the floor with our spikes!). The “Velferden” system here includes a cozy cafeteria and common area, recreation area with pool and foosball, and a dancehall themed after Roald Amundsen’s flight of the Norgeairship to the North Pole, soon to be the site of the world’s northernmost karaoke party.

A corner of the “dancehall” in the Servicebygget (Mess Hall). Saturday nights there are parties here, with music and volunteer bartenders. The dancehall is decorated in honor of the airship Norge, the first vessel to overfly the North Pole, which was led by Roald Amundsen, and which made its final stop in Ny-Ålesund before making the trek to the Pole on May 11-12, 1926. Credit: Doug Rowland

The “Syk” dormitory, once the site of an infirmary, houses several of the VISIONS-2 science team. The rooms are compact and space-efficient, each with a private bathroom and internet access. Credit: Doug Rowland

Tonight, the Norwegians have kindly offered to help us celebrate Thanksgiving with a formal meal, and some of the NSROC staff have been helping with recipes and with the food preparation. We’re all looking forward to a taste of home as we move into a day off tomorrow before completing the payload preparations next week.

Members of the VISIONS-2 team gather to help the Kings Bay staff cook a Thanksgiving meal, which the team will enjoy Saturday, November 24. From left to right: Koby Kraft, Glenn Maxfield, Jorge Camacho, Tim Wilson. Credit: Doug Rowland

Aurora and stars over Ny-Ålesund. Credit: Chris Pirner

Two hundred people; two centuries, in the Roman style. That’s what it takes to launch two rockets from the top of the world. One hundred here and another hundred back home to help with the designing and the building and the testing and the shipping and to take each of the thousand steps between an idea and the reality.

We are sixty-one team members in the field, Norwegians, Canadians, and Americans, technicians, engineers, and scientists. Payload team, instrument team, motor team, launcher team. Telemetry and tracking team, range team, safety team. All working together at the end of the Earth, far from home.

Members of the VISIONS-2 payload team as they await their flight from Longyearbyen, Svalbard, to Ny-Ålesund. From left to right: Frank Waters, Jorge Camacho, Norman Morris, Mark Frese, Eric Taylor, Ted Gass, Koby Kraft, Ahmed Ghalib, Mike Southward. Credit: NASA

Then there are the Kings Bay staff. Pilot, purchaser, plumber, chef, cooks, and carpenter, harbormaster, mechanic, electrician, and the rest of the twenty-three souls that live here in Ny-Ålesund, keeping this community running through the long polar night. Rounding out our first century are the other workers and researchers at the Polar Institute, here in scientific communion.

In our second century are the team members we left at home. The machinists who turn solid aluminum into sleek and elegant instruments, each unique, purpose-built. The designers and technicians who imagined and then built each of the myriads of circuits and pulled the miles of electrical wiring. The administrative staff who make sure the bills get paid, the travel arrangements run smoothly, and emergencies are handled quickly and efficiently. For three years this team has worked so that the field team could spend weeks in the high Arctic, preparing our rockets and experiments.

We have journeyed to Ny-Ålesund, Svalbard, the northernmost town in the world, so that we can touch the sky.

Ny Ålesund is the northernmost year-round civilian settlement in the world. On the shores of the Kongsfjord (King’s Bay), it benefits from the warm waters of the Gulf Stream, which provides an ice-free harbor year-round. Once an important home of coal mining, it has changed focus to scientific research. At 78.9° N, the town is only 1237 km from the North Pole, and over 5700 km from Washington, DC.

We are here because the harbor, even at 79° N, is open year-round. We are here because during the months of winter night, there is no Sun to share the sky with the shining aurora. We are here because there is a modern rocket launch facility on the shores of Kongsfjorden, once a home of fishermen and coal miners. Now our aim is a different kind of extraction – prying the mysteries of our upper atmosphere from the cold blackness.

The last sunset I saw as I flew north from Oslo to Longyearbyen, Svalbard. This photo was taken near Tromsø, out the window of the airplane. Our team will not see the Sun again until they head south after the launch. Credit: Doug Rowland

We are here because this is the one inhabited place on Earth that, every morning, passes directly underneath a weak point in our world’s magnetic bubble, a funnel that channels the fierce solar wind into our upper atmosphere, sparking auroral displays, and boiling the gases of our atmosphere off into the vacuum of space. We are here to learn how this happens, and to take a picture.

Our mission, VISualizing Ion Outflow via Neutral atom Sensing (VISIONS-2), will launch from Ny-Ålesund, Svalbard, between December 4 – 18, 2018. VISIONS-2 is part of the Grand Challenge Initiative — Cusp, a dedicated sequence of 12 rockets launching over 2 years to study the interaction between the magnetic cusp and the upper atmosphere. The Grand Challenge is a multinational cooperative agreement between the US, Norway, and Japan that provides for open data sharing and scientific collaboration. The three nations are leveraging existing infrastructure to optimize scientific return from missions launched by all three countries.

Like the old daguerreotypes, this picture will be primitive. It will be grainy. It will be such a long exposure as to blur the impatient atoms as they champ and strain under Earth’s gravity. But this picture will reveal, in false-color chiaroscuro, the locations and strength of fountains of gas that shoot high out of the atmosphere, driven by the intense electric currents that course through the aurora.

Unlike the daguerreotypes, our picture does not register light striking a silvered plate. Our picture is built up by a glass plate that detects the impacts of very fast atoms, racing past their neighbors like a Formula 1 car overtaking a marathon runner. These atoms undergo their own marathon journey, traveling tens or hundreds of miles from the fountains where they are born. But to see them, we must go to space. This because our planet’s thick atmosphere absorbs any atoms which travel down towards us on the ground, blanketing us in ignorance and shrouding these fountains in mystery. Only a camera lofted above, to altitudes above this shroud, can reveal these atmospheric fountains and their link to the ghostly aurora.

So, we come to this place, the only one on Earth like it, bringing rockets to lift our cameras high. We come here in the long winter night, our way lit by the aurora’s iridescence, and our hearts warmed by the welcome of our Norwegian friends and colleagues. We come here in the spirit of international cooperation and scientific endeavor to learn about our world, and perhaps, about ourselves.