The R/V Revelle.

By Eric Lindstrom

I am writing this while on a plane headed toward Honolulu to join the Research Vessel (R/V) Roger Revelle for six weeks at sea in the Pacific Ocean. It feels great to be heading to sea again. This NASA field campaign will last more than a year, with intense shipboard work near the beginning and end of the year. A web of sensors will be deployed to monitor one oceanic region over an entire year.

As Physical Oceanography Program Scientist at NASA Headquarters for nearly 20 years, my primary job is supporting our satellite missions related to measuring physical characteristics of the ocean (principally, temperature, salinity, sea level, and winds) and supporting the oceanographers that generate knowledge from such data. True understanding requires our fully appreciating the variations of the satellite data in the context of ocean physics. And that requires getting out there and getting wet from time to time!

Your blogger, Eric Lindstrom.

R/V Revelle (home port: Scripps Institution of Oceanography, San Diego, California) leaves Honolulu on 13 August 2016 and returns to Honolulu on 23 September. The central location of the field work is about 8 days voyage southwest of Hawaii at 10N, 125W. Details of the expedition plans are available here. I hope to bring you a steady stream of expedition blog posts between now and the end of September 2016, including why NASA is focusing attention on this particular spot in the open ocean.

Since NASA’s launch in June 2011 of the Aquarius instrument to measure ocean surface salinity from space, the agency has embarked on field campaigns to understand surface salinity in great detail. This work has illuminated new ways of thinking about the ocean’s role in the global water cycle. Our field campaign, dubbed Salinity Processes in the Upper Ocean Regional Study-2 or SPURS-2, is the latest work to link the remote sensing of salinity with all the oceanic and atmospheric processes that control its variation.

The ocean is the primary source of moisture for the atmosphere. Evaporation of water from the sea surface leaves the ocean saltier (more saline). Precipitation over the ocean leaves the ocean fresher (less saline). The global pattern of average salinity at the sea surface approximately represents the balance of evaporation and precipitation at any locale (other factors such as river runoff, ice melt, and ocean motion and mixing complicate the picture). Many details of the interaction between ocean and atmosphere that lead to moisture transfer and signatures in ocean salinity are poorly understood. SPURS-2 is particularly focused on how, in one of the rainiest places on Earth, rainwater enters and impacts the ocean. Through this blog during the coming month, you will hear more about how and why oceanographers focus on such a problem.

The first SPURS campaign, which took place in the North Atlantic Ocean in 2012-2013, focused on the study of ocean processes where evaporation dominates the salinity of the surface ocean. I blogged during the September 2012 work from R/V Knorr. Among other things, we learned that surface salinity variations in that part of the world can be directly connected with precipitation patterns over the nearby continents. I’ll discuss that scientific finding and others in this blog over the coming month.

At the opposite extreme from SPURS-1, SPURS-2 focuses on an oceanic regime where precipitation dominates the salinity characteristics of the surface ocean. The two extremes call for significantly different approaches to measuring and studying the upper ocean. We will uses many of the same tools from SPURS-1 (instrumented moorings, profiling floats, surface drifters, and gliders) but deployed in new and novel ways.

The crew and scientific party on R/V Revelle will be more than 50 in all. As you read future blog entries you will get some sense of what its like for such a group to work closely together for six weeks in the confined space of an oceanographic research vessel. Seasickness? Food? Watches? Sleep? Drama? Boredom? Sea life? You’ll find out soon and get a sense of how some oceanographers go about their work, what technologies are involved, what is discovered, and how all this impacts lives, including yours, and what you might experience if you were aboard.

By Eric Lindstrom

“Ships at a distance have every man’s wish on board.” — Zora Neale Hurston

So, we are back in port in the Azores Islands of Portugal. Knorr 209-1 was a fabulous voyage and it did feel that we had many a man’s wish on board. Those included wishes for our data collection from all the scientists involved in SPURS and well wishes from all the family members of the expedition and finally the good wishes of you, my blog audience.

Thank you all for following my SPURS adventure so far. The saga continues for another year. We have instruments in the water and more expeditions ahead (in March and September 2013). Each expedition will be slightly different in nature but overall working toward the SPURS goal of understanding the surface salinity maximum in the Atlantic and the water cycle on the planet. I’ll be going into a different mode of blogging now, to provide you updates on the science and the observations as the year goes along. With good fortune, I will get back to sea for the final leg of SPURS in September 2013. If you would like another voyage blog from the Sargasso Sea in 2013, let your voices be heard in the comments section below!

After several days of riding a lumpy swell from Tropical Storm Oscar, we were greeted by the magnificent sight of greenery and civilization at Ponta Delgada on the island of São Miguel.

The expedition was a success scientifically. We got our sensor web in the water for the coming year: three moorings, 25 Argo floats, 18 surface drifters, three Wavegliders, three Seagliders, and a Lagrangian Mixed Layer Float. We completed a wide variety of shipboard deployments: 764 Underway CTD casts, 100 CTD/LADCP Stations, 30 Vertical Microstructure Profiles, 33 AUV missions, three Slocum glider turbulence missions, and a full suite of continuous measurements including ocean velocity profiles, thermosalinograph and meteorology/fluxes. We accomplished the objectives we had laid out for us – deploy the sensor web (week 1), do a control volume survey around the moorings (week 2), and map a mesoscale ocean feature (week 3). We were able to squeeze in some extras, like a 24-hour time series in the saltiest water and pick up a glider from the French expedition in August.

The expedition was a success for NASA and WHOI. We even caught the attention of the International Space Station and had a great 30-minute chat with Commander Sunita Williams about research in sea and space and the strong connections between the space program and oceanography.

The expedition was a success in interagency cooperation. SPURS is led by NASA, but has enormously important contributions from NSF, NOAA, and the Office of Naval Research. It takes a village to put on a good oceanographic process study!

I created a “SPURS Illustrated Campaign Summary” from our Knorr expedition. I will make it available to all of you as part of a future post. There will also be movies available from the Space Station call and from the expedition, which are still in the editing process.

Your questions and comments on SPURS are always welcome. Use the comments section of any of the posts and I will get the message. Your interest and curiosity provides directions for future blogs and helps me put into words some of the technical aspects of SPURS that may not be fully understood.

Thanks you all for again following along on our Knorr SPURS expedition. There is much more to come, so stay tuned!

By Eric Lindstrom

Channel fever: an unusual excitement or restlessness common among a ship’s crew when the ship nears port after a voyage (The term probably refers to the English Channel, between southern England and northern France.)

Now that all the oceanography is done, it’s four days of steaming to the Azores. During that time there is still plenty to do. A shipping container is being prepared for freight to Woods Hole. People are comparing notes on their flights out of the Azores and taking guesses at what time we will be getting off the ship.

We are writing expedition reports (something your blogger has pretty well in hand!). I took over 2,000 pictures during the voyage and wrote 32 blog posts. I plan on finishing this trip with an epilogue as next posting. Then, after I return home, you will be able to access my presentation entitled “An Illustrated SPURS Campaign Summary,” which captures the entire expedition accomplishments in pictures. Remember too, if you have become a fan of SPURS, that there are more expeditions in 2013 and a sensor web in the water until next October. I will be blogging periodically to keep you up-to-date on developments and findings. For now, I need a rest from blogging. It feels like channel fever!

Personal gear has to be packed and cabins cleaned. That leaves people with time to think about what they will be doing in the Azores or when they get home. People are laughing more and joking more. Sometimes, with all this activity, happiness emerges as channel fever.

Maybe it’s the transformation of the ship – from being loaded down with gear to empty cleanliness. There are empty reels and baskets indicating our success at deploying moorings. The CTD master control station, hub of so much activity for the past weeks, is now quiet. Everywhere you look, it’s looking like its over. It’s enough to bring on channel fever.

We are taking stock at what we have done. We deployed three moorings, 100 CTD stations, 764 Underway CTD casts, 25 Argo floats, 18 surface drifters and a Lagrangian float. We left three Wavegliders and three Seagliders patrolling the seas near the moorings. The salinity field over a 120×120 mile piece of ocean was pretty well mapped. We have gigabytes of data to sift through and analyze. And we are pleased. We are weary. And we know when we see the Azores we are nearly home. That feels like channel fever!

We leave the lovely blue Sargasso Sea in our wake, but we can feel the harbor channel in Ponta Delgada, Azores in our future. We feel the accomplishment of the mission, and the promise of home. That is channel fever.

By Eric Lindstrom

When on land, an oceanography brain usually associates the term ocean motion with the movement of seawater in the form of ocean currents.

Depictions of ocean surface currents derived from satellite data can be viewed at NASA’s OceanMotion.org web site.

However, when actually on the ocean, the biggest signal for our oceanography brains to cope with is the role of ocean motion in the pitch and roll of the ship (due to wind seas and swell). OK, so I am telling you that feelings matter. If you have ever been seasick, then you know what I am talking about!

So, if you spend 33 days on a small vessel at sea, you get a great appreciation of ship motion. There are actual six axes of motion of two kinds (lateral and rotational). Laterally there are surge (fore and aft), sway (port and starboard), and heave (up and down). Rotation also occurs around three axes that are more commonly discussed (maybe because we feel them more?). They are pitch (around port to starboard axis), roll (around bow to stern axis), and yaw (around the vertical axis). We can definitely feel all these motions but some do matter to our feelings more than others. Perhaps the most noticeable ones for land-loving creatures like humans are heave (the accelerating elevator feeling) and rotational motions largely absent in our daily lives (pitch and roll). Together, these can be combined into a kind of perfect storm of corkscrew-like motion that weakens the resolve of even veteran mariners. Lucky for us, the SPURS cruise has been pretty calm and no one has been suffering from seasickness.

By far the most noticeable and everyday motions on a ship are that of pitch and roll. Pitch is especially noticeable when navigating into a swell or into the wind. Going downwind or in the direction of the swell is much more gentle pitch-wise (sailors are wished good luck by offering them “fair winds and following seas”). Roll is especially diabolic when one is navigating nearly parallel with the troughs and crests of the swell. This is something you DO NOT do when the seas are large because you may very well roll over (not good; do not try this at home!). Faced with large seas, the safest course is to ride the weather facing into the wind and waves (and just suffer the horrible pitching).

Sorry to go on for so long about the ship motion, but its an ever present partner to our expedition and you deserve a share for sticking with us!

You may be wondering about the difference of wind seas and swell. Good question! Swell and wind seas are both manifestations of surface gravity waves. Swell is caused by wind forcing of the ocean in some remote location. Wind seas are the jumble of more disorganized waves that come up directly under and within a wind event. There has been a good swell running in the SPURS region for the last two weeks due to Hurricane Nadine hundreds of miles away. On top of the swell, the wind waves cause whitecaps and noticeable roughness above wind speeds of about 10 miles per hour.

Well, on Knorr we are not out here to study wind waves (just feel them). I should get on to talking a little about ocean surface currents. Our main focus is the surface salinity and how it gets to be the way it is. Ocean currents moving patches of different salinity around is one key factor in accounting for salinity changes at any site in the ocean (we call this advection of salinity). The Ocean Motion web site produced for the NASA Physical Oceanography Program has a wealth of background information on ocean surface currents. Here in SPURS we believe there are only weak average currents (a year of moored measurements will determine that for sure), but that the wind-forced transient currents play an important role in the local water cycle (and surface salinity values). One obvious reason to think this is that the salinity maximum here is hundreds of miles north of the maximum in evaporation minus precipitation. The simplest explanation for this displacement is the northward movement of surface waters induced by the trade winds. On average, upper ocean waters forced by wind move 90 degrees to the right of the wind in the northern hemisphere so the easterlies of the trades give the ocean waters a push toward the north. This hypothesis will be tested by the SPURS observations over the coming year.

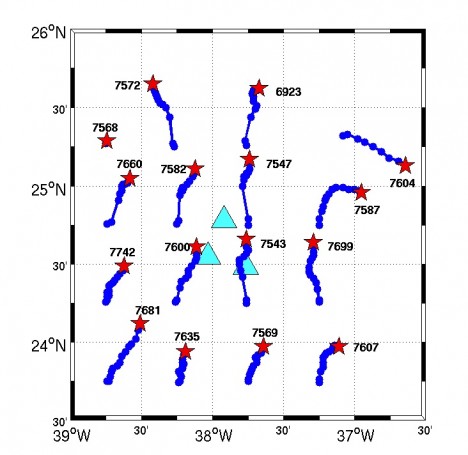

SPURS Argo float locations over time indicating flow at their parking depth of 3,300 ft. (Courtesy of Jessica Anderson.)

Out here it is extraordinarily difficult to fully appreciate the complexity of the currents around us in the upper ocean. The average current is small, but there are eddies and fronts with stronger flows around us that we observe sporadically as we move around from hour to hour.

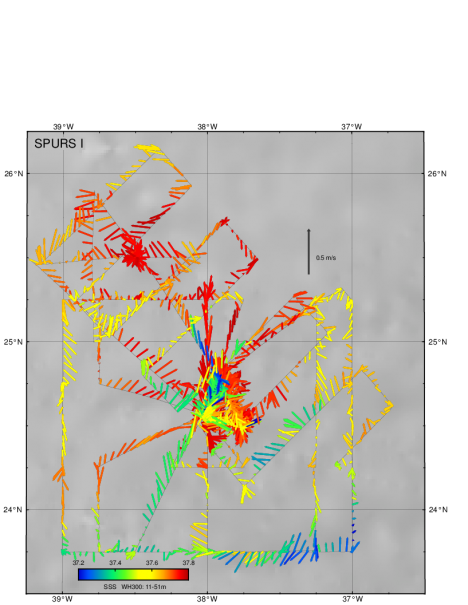

Map of current vectors in the upper 167 feet (51m) along our track color coded by the surface salinity. (Courtesy of Phil Mele.)

We will only be able to make sense of our hour-to-hour estimates of ocean motion once we return to shore and can fully integrate the satellite and model information into the picture. We obtain details profiles of current vectors on each station but honestly have a tough time “connecting the dots” in real-time. It will take a good bit of analysis to understand the complex flow field.

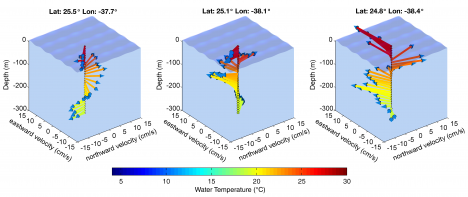

Vertical variation of velocity vectors at three adjacent stations on the same day. (Courtesy of Julian Shanze.)

It feels a little like mapping Washington, D.C. in one day, from your car, driving around with a simple still camera. We get some great snapshots, but we can only place them in a larger context when be have full access to maps, satellite images, and historical records (stuff most people cannot examine in their car while driving around!)

As in rest of life, context is important in oceanography. We strive for it, but as with most things, the perspective of hindsight provides the best context. Feeling seasick is no exception! It’s so awful in the moment, and such a trifle in the glory of the entire expedition.

By Eric Lindstrom

How do you spell physical oceanography? I know my answer for that question! It’s easy: CTD.

For about the last 40 years, the mainstay of physical oceanography has been profiling the ocean with sensors for Conductivity, Temperature, and Depth (CTD). The SPURS cruise is no exception. These are key properties to derive salinity and the physical state of the seawater is described through the “Equation of State” which depends on temperature, salinity and depth.

During SPURS, we are doing CTD stations from four to six times per day (to around 3,300 feet depth) and using an underway CTD as frequently as every 15 minutes (to about 1,300 ft). Computers aboard transform the raw sensor data into temperature, salinity, and depth information at regular levels (say every 3 feet) depending on the need. From there, it is relatively easy to use the equation of state to derive density and to estimate the geostrophic currents between the various CTD casts. Those are the currents caused by pressure variations resulting from the spatial density differences (like the winds between high and low pressure systems in the atmosphere). So CTD helps us unlock a major piece of ocean circulation, right there.

The CTD is the basic instrument embedded in most of our platforms – on gliders, moorings, autonomous vehicles, and our Knorr thermosalinograph. All use similar sensors in slightly different configurations. All the incoming data is converted to temperature and salinity data spread through space and time. Different CTDs on different platforms are specialized to measure different time and space scales of the temperature and salinity fields. So, some CTDs measure the microstructure at inches and smaller, and some better measure the variations over the full ocean depth. Some work best while moving rapidly through the water, while others are specialized for stationary measurements. Any way you cut it, you still spell physical oceanography with a CTD.

Over the course of one SPURS expedition the number of CTD stations may number in the hundreds. And since we launch the underway CTD as often as possible as we go between stations, as many as a thousand underway CTD profiles are collected over a month at sea. The usual arrangement for CTD profiles is to mount the instrument inside a metal frame and pairing it with a rosette. On the rosette, one can mount Niskin bottles (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nansen_bottle ) for collecting water samples. The Niskin bottles are cocked open before the CTD cast and are tripped in sequence. Samples are then extracted on deck for calibration of salinity (or any other purposes).

All in all, the CTD is THE instrument of SPURS and the mainstay of physical oceanography since the 1970s. It was used to map the properties of the global ocean in the World Ocean Circulation Experiment in the 1990’s. In SPURS it will provide us with an unprecedented view of the salinity variations here in the highest salinity region of the Atlantic Ocean.