NASA’s DC-8 is usually the aircraft flown from South America to Antarctica for the IceBridge mission’s annual research flights over the continent. But this year, the DC-8 was booked for a different mission, so NASA’s P-3 filled in. Since late October, the P-3 crew and instrument operators have been making flights out of Ushuaia, Argentina, to map Antarctica’s ice.

The scenery outside is stunning and the amount of data collected enormous. But as often as people ask about Antarctica and the mission’s science goals, people also want to know about P-3. As the following images show, this is not your typical aircraft.

Here’s a peek inside the P-3 flying research laboratory, from front to back.

The NASA P-3 sits on the ramp at the airport in Ushuaia, Argentina. Photo by Aaron Wells/Indiana University.

NASA pilot Jay Stapleton waits to fly. Pilots work in shifts during the nine-plus hour flights.

NOAA pilot Patrick Didier flies the P-3 during the November 12, 2017, flight over the Larsen C ice shelf.

John Sonntag, NASA IceBridge mission scientist, monitors data collected during a research flight on November 12, 2017.

IceBridge project scientist Nathan Kurtz (front), and Dennis Gearhart of the Digital Mapping System (DMS) team (back) monitor imagery acquired during the research flight on November 14, 2017.

The view from the back of the P-3 shows how the aircraft has been modified to support racks of computers and science equipment.

In the nine-plus hours it takes to fly from Argentina to Antarctica, collect data over the continent and fly back again, people on board are bound to get hungry. There is a microwave on board, as well as some snacks and hot drinks. But there are no flight attendants, and there are no meal carts. NASA’s P-3 is equipped primarily for science.

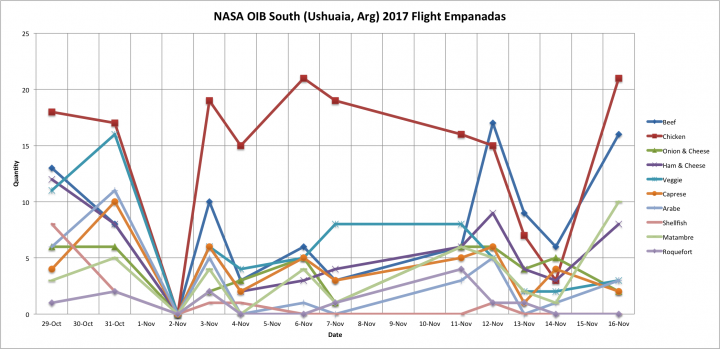

But that doesn’t mean instrument operators and crew go hungry. In addition to working with the airport and local government to ensure paperwork is in order, Operation IceBridge deputy project manager Eugenia De Marco also takes on the task of ordering and procuring daily orders of … what else … empanadas. And she approaches the task like only an engineer would.

Every evening, De Marco opens an Excel spreadsheet and records the orders of approximately 15 people. The orders are tallied and delivered via text message to Nicolas Furlanetto, owner of Ushuaia restaurant Doña Lupita. The next morning, Furlanetto and his staff arrive at the restaurant by 6:30 a.m.—hours earlier than on a typical day. Anywhere from 23 to 85 fresh empanadas are lifted from the wood-burning stove, neatly wrapped in paper, and labeled with our names.

If none of the 11 varieties of empanadas speak to you, pizza and sandwiches are options too. But most of us stick with the empanadas, filled with everything from beef to Roquefort cheese. According to Furlanetto, the “matambre” and “carne a cuchillo” are the varieties most often ordered by locals. Our group bucks the trend. De Marco prepared a chart based on our empanada order history, and the data show chicken is the clear winner.

This photograph shows finger rafting in sea ice, captured during the Operation IceBridge mission on November 14, 2017. Photo by NASA/John Sonntag.

“I don’t understand it. I haven’t been this perplexed about the weather in the Weddell Sea area for years,” said John Sonntag, mission scientist for NASA’s Operation IceBridge mission. Sonntag is a self-described weather geek. He is also world-renowned for his insight into the weather in West Antarctica.

Instrument operators, flight crew, and various IceBridge support people gathered on the evening of November 13 in Ushuaia in a hotel conference room, where they listened to Sonntag’s synopsis of the weather situation. A number of factors go into choosing which of the science targets to fly. Weather is a big one. Not only for safety, but most of the instruments on board need little to no clouds in order to make measurements. One thing was certain: weather permitting, the next day’s mission would be over Antarctic sea ice.

According to Sonntag, the location of a high-pressure ridge should cause wind to blow from north to south immediately east of the peninsula. That would cause fog to form when it reached the Weddell Sea; farther from the peninsula the fog would clear as the winds reversed around the ridge. Some models agreed, but others called for the opposite. That’s the challenge faced by Sonntag and IceBridge project scientist Nathan Kurtz, who had to decide whether to fly a mission the next day. Which weather forecast model do you trust? And which remaining mission plans will provide the most scientific value?

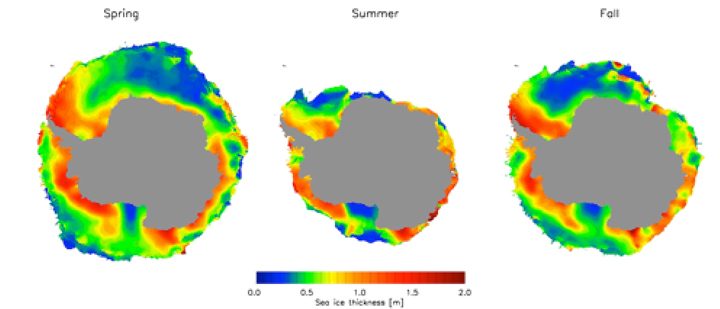

The main goal of flights over sea ice is to map its thickness. That’s typically done with a satellite, but the ICESat mission ended in 2009 and ICESat-2 is scheduled to launch in 2018. In the meantime, thickness can be measured from aircraft with a radar instrument by timing how long it takes radar waves to penetrate the layers in the sea ice.

Data from ICESat were used to construct these maps of sea ice thickness around Antarctica. In lieu of a satellite, data from Operation IceBridge is used to map sea ice thickness in targeted areas.

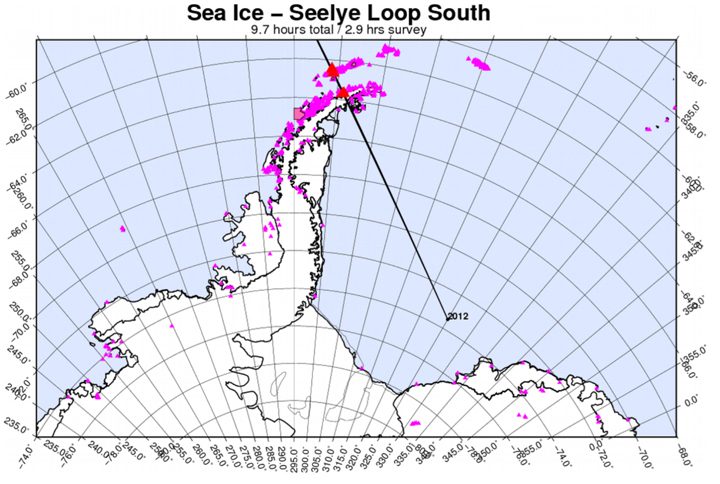

On the morning of November 14, Kurtz and Sonntag re-evaluated the forecast models and Kurtz made the final call: The “Seelye loop south” mission over sea ice was a go. The nearly 10-hour mission, flown almost every year since IceBridge started making flights over Antarctica in 2009, is essentially an out and back line over the Weddell Sea. At this point in the campaign—more than halfway through and with plenty of allotted flight hours remaining—he decided to play the odds. Time would tell where the clouds really were.

On November 14, 2017, John Sonntag (left) and Nathan Kurtz (right) evaluate the newest forecast models before deciding whether to fly a sea ice mission. Photo by NASA/Kathryn Hansen.

This map shows the planned flight line for the “Seelye loop south” mission.

As I’m writing, we’re flying over the Antarctic Peninsula toward the Weddell Sea. Fog extends all the way to the ground but you can still make out the faint shapes of rock outcrops. A moment later the fog dissipates. Kurtz watches out the window and smiles. “It’s exhilarating, it’s a lot like gambling.”

Fog (top) gives way to clear skies (bottom) over the Antarctic Peninsula. Photos by NASA/Kathryn Hansen.

Nathan Kurtz is relieved to see the skies turn from foggy to clear over the Antarctic Peninsula. Photo by NASA/Kathryn Hansen.

Instrument operators monitor the incoming data. Flying at an average altitude of 1,500 feet (sometimes as low as 1,000 feet), I spot the occasional seal. Then, as we continue along the flight line we become sandwiched between layers of clouds. It’s hard to tell where the sky ends and the ice begins.

Pilots fly the P-3 between layers of clouds.

But as fast we encountered the clouds, we leave them behind again. “It was a roller coaster, up and down,” Kurtz says as we head back to Ushuaia. “But now I’m excited, the flight went well.”

Perhaps you know the feeling: that moment when you see with your eyes something you have previously only seen in pictures. Before today, I knew the Larsen C ice shelf only from the satellite images we have published since August 2016. The attention paid to the shelf off the Antarctic Peninsula has been due to a rift that eventually calved an enormous iceberg. Today (November 12), the Operation IceBridge mission flew its suite of airborne instruments over the shelf and I caught a first-hand look.

The view from the P-3 after take off shows mountains that received an overnight dusting of snow in Ushuaia, Argentina. Photo by Aaron Wells.

I was aware that I would be seeing an iceberg the size of Delaware, but I wasn’t prepared for how that would look from the air. Most icebergs I have seen appear relatively small and blocky, and the entire part of the berg that rises above the ocean surface is visible at once. Not this berg. A-68 is so expansive it appears if it were still part of the ice shelf. But if you look far into the distance you can see a thin line of water between the iceberg and where the new front of the shelf begins. A small part of the flight today took us down the front of iceberg A-68, its towering edge reflecting in the dark Weddell Sea.

The edge of A-68, the iceberg the calved from the Larsen C ice shelf. Photo by NASA/Nathan Kurtz.

This particular flight, however, aimed to get more than just a surficial look at Larsen C; to understand the system as a whole, scientists also want to know the bathymetry of the bedrock below. To do that, the flight path was planned with gravity measurements in mind. While radar instruments can “see” through snow and ice on land to map the bedrock, radar has trouble when instead of land there is water below the ice. For the gravimeter, that’s not a problem. The new flight lines—flown for the first time—followed the ground tracks of the future ICESat-2 satellite, and simultaneously increased the area of Larsen C mapped with the gravimeter.

John Sonntag, Operation IceBridge mission scientist, takes notes during the science flight over Larsen C. The planned flight lines are in the foreground.

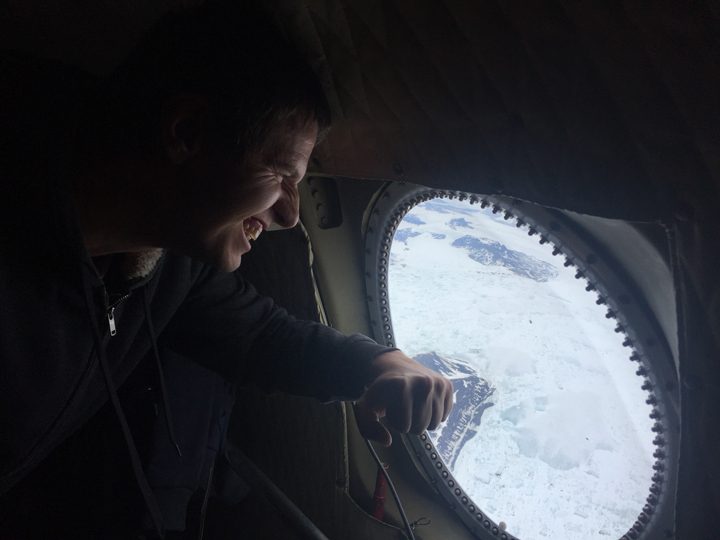

Nathan Kurtz (IceBridge project scientist) and Sebastián Marinsek (Instituto Antártica Argentino) observe Larsen C from a window on the P-3.

Taking off from Baltimore Washington International Airport on November 6, the view out the window was stunning. If the foliage wasn’t exactly at peak autumn color, it was close. Landing in Buenos Aires the next day was equally beautiful, but it was the purple blooms of the jacaranda trees that caught my eye. And upon landing in Ushuaia the day after that, I noticed vibrant red blooms on the shrubs. Within 48 hours and 6,500 miles, I went from autumn to spring.

Spring flowers bloom in Ushuaia, Argentina. Photo by Kathryn Hansen.

An Aerolineas Argentinas flight lands in Ushuaia. Photo by Kathryn Hansen.

Ushuaia (blue dot) is known as the southernmost city in the world. The red pin is Buenos Aires.

Spring in the Southern Hemisphere is when NASA makes annual science flights over Antarctica. The flights are part of Operation IceBridge, NASA’s longest-running mission to map polar ice (now in its ninth year in the Southern Hemisphere). But for the first time, flights over the icy continent are being staged from Ushuaia, Argentina, instead of Punta Arenas, Chile.

Upon arriving in Ushuaia, I met some of the IceBridge scientists and caught up on the status of our aircraft, the P-3. Most people have already been here for a few weeks, as science flights began on October 29.

For the next 10 days, I will be your blogger in the field. These Notes from the Field will differ from others, which are typically written by scientists. I am not a scientist. But as a writer for NASA Earth Observatory, I look forward to being your eyes and ears in the field, delivering stories about the people and the science happening at the bottom of the world.

This hangar will be our office. As the photograph shows, the office is a bit sparse today. Engineers are waiting for parts to arrive to repair a window through which the Airborne Topographic Mapper makes its observations.

The hangar in Ushuaia. The P-3 is on the ramp south of this image (not pictured). Photo by Kathryn Hansen.

On a no-fly day, the office in the hangar is sparsely populated. Photo by Kathryn Hansen.

In the meantime, many took a break from nearly non-stop work for a quick camping trip. I caught up with a group that needed to use the spare time to install the magnetic ground station. This is essentially a point on the ground where the magnetic field is known. Flying over that point gives researchers the information—ground-truth—that allows them to make corrections in the data collected inflight by the magnetometer.

The gravity and magnetics team loads gear into the truck. Photo by Kathryn Hansen.

Katrina Zamudio of USGS (right) installs the magnetic ground station. Photo by Kathryn Hansen.

On our way back to the hangar, our kind escort gave us a tour of airport grounds and the shores of the Beagle Channel, where we did some beachcombing. It’s back to work tomorrow!

On our way back to the airport we made a quick detour for a closer look at the shoreline. Photo by Kathryn Hansen.

Shells crunched under our feet as we walked on the beach. Photo by Kathryn Hansen.