The last time I saw the small promontory off Herradura Bay in the Gulf of Nicoya, it was 31 years ago aboard the German research vessel Victor Hensen, named after the pioneer 19th-century German marine scientist who devised some of the earliest tools to investigate the biology of the smallest oceanic organisms, the plankton. In 1994, as a 25-year-old marine biology graduate from the Universidad Nacional de Costa Rica (UNA), I was fortunate to be selected to represent UNA on a joint expedition with the University of Costa Rica (UCR) and a German marine research institute. It was a rare opportunity to conduct research aboard a state-of-the-art vessel off the coast of my own country.

That evening, three decades ago, we anchored off Herradura Bay for an “anchor station” to study how the Gulf of Nicoya exchanges water and nutrients with the Eastern Tropical Pacific Ocean. The Gulf sits at the convergence of the Cocos and Caribbean tectonic plates, where oceanic waters mix with riverine waters. As the Cocos Plate slowly subducts beneath the Caribbean Plate, it shapes the land and seascapes that influence the climate and ecology of Central America.

Recently, I returned to the Pacific coast of Costa Rica for another international expedition, this time with NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center (GSFC) Ocean Ecology Laboratory’s Field Support Group (FSG). For the past 15 years, I’ve worked with the FSG as a contract scientist, supporting NASA’s mission to collect and distribute data from satellites that measure ocean color. These data provide valuable insights into the biological components of the ocean, which can help scientists, policymakers, and resource managers better understand ocean ecosystems.

Our hosts for this expedition are scientists and policy specialists from Costa Rica’s Fishing Federation (FECOP), led by Dr. Marina Marrari, an energetic Argentinian oceanographer based in Costa Rica and former postdoctoral fellow at NASA’s Ocean Ecology Laboratory. Our mission is part of a collaboration under the Airborne Validation: Unified Experiment Land to Ocean field effort, which seeks to calibrate a new class of space-borne imagers for tropical vegetation and ocean research. But this collaboration with Dr. Marrari began many years ago, when she became part of an early adopter project for NASA’s latest ocean color satellite mission: the Plankton, Aerosols, Clouds, ocean Ecosystems (PACE) mission. PACE is part of this new class of spaceborne imagers that gathers data from well over 200 wavelengths, providing new insights into how the Earth system works and, in particular, on ocean biology, including phytoplankton—the foundation of the marine food web. These plant-like organisms produce about half of the world’s oxygen and fuel the marine food chain.

FECOP’s work intersects with NASA’s objectives in studying the rich pelagic biodiversity off Costa Rica’s Pacific coast. These waters support regional fisheries and a growing sportfishing industry that draws thousands of tourists each year. According to FECOP, sportfishing contributes over 2 percent to Costa Rica’s GDP—comparable in relative terms to the entire construction sector in the U.S. in 2024.

For NASA, this expedition offers a chance to validate and improve satellite measurements in a region with unique optical characteristics. The algorithms NASA uses to estimate biological parameters, like chlorophyll, rely on data from across the globe but may not be suitable, for example, for detecting harmful algal blooms (HABs or “red tides”) in specific regions, like the Gulf of Nicoya in the central Pacific side of Costa Rica. Water color is influenced by various factors, and a particular optical signal can indicate different biological or chemical processes in different regions.

Local scientists from UNA and UCR participating in the expedition play a critical role in enriching our measurements. A key focus is understanding regional phytoplankton, especially those that can cause HABs, which pose risks to public health and local economies. By refining satellite data with local expertise, we hope that our measurements can lead to region-specific algorithms for early warning systems that can detect HABs and alert authorities.

NASA’s data have already proven invaluable for sportfishing enthusiasts. Satellite information on surface ocean temperature, chlorophyll, and other oceanic parameters has been integrated into PezCA, a mobile app developed by FECOP, helping fishermen forecast fish catches and potentially reducing fuel costs while maximizing the value of Costa Rica’s tourist sector.

Costa Rica is internationally recognized for its sustainable tourism and biodiversity conservation efforts. Now, with the help of spaceborne sensors capturing oceanic data, the country can extend these efforts to its vast territorial waters, which are 10 times larger than its landmass.

Returning to the coast of Central America, the same waters that first sparked my scientific journey, has been an emotional homecoming. Reconnecting with old colleagues, witnessing the growth of a new generation of talented scientists and policymakers, and being part of this expedition has been a truly colorful experience. This journey is a reminder of the vital, enduring connections between science, the collaborative efforts of local communities, and multidisciplinary researchers working together to protect and better understand our oceans.

Today marks day 12 of the AVUELO campaign, and what a whirlwind it has been! It feels like just yesterday we were kicking things off, but with so many moving parts, time has flown by. Between the flight team, field crew, and lab team, we’ve had two major components to manage: terrestrial and coastal operations.

What makes this campaign particularly exciting for me is my deep connection to Panama. Having spent a large part of my childhood in the area we are sampling, it feels almost surreal to be back here working on such an important project.

Every day begins early, around 6:30 a.m., to check the weather to determine if the airplane will fly. I then jump on a teleconference to discuss with the flight team and project members whether the conditions are right for the day’s flight. So far, we’ve had four flight days in Panama, although unfortunately, the weather has been challenging, with heavy cloud cover over most of our area of interest. This year has been one of the wettest dry seasons in recent memory in Panama, but despite the weather, we’ve managed to secure some great data not just over our primary sites but also over secondary sites of interest.

The field teams are truly a well-oiled machine at this point. They leave at the crack of dawn, ready to collect leaf samples. The sites vary, so some teams hike to their sites, while others take boats or even use cranes to access the canopy. The goal is to collect samples from the very top of the trees, which can be a tricky task when the trees are tall. For the canopy team, it’s a breeze—they simply sample from the top. For others, the process involves creative methods like using long poles, slingshots to throw ropes around branches, or other creative means! In one memorable moment, a group of parrots inadvertently helped out by knocking down a few leaves as they flew off a tree. Once the samples are collected, they’re stored in bags, carefully noting the species and location. The team then returns to the lab, typically past noon, where the lab work begins.

In the lab, the samples undergo various analyses. Different stations process the samples, one measuring the spectra of the leaves (including transmittance and reflectance), another measuring leaf mass area, and yet another focusing on the stomata. Some samples are ground up to be analyzed later for their composition. It’s an intricate process, but every bit of data we gather is important to better characterize the plant.

Though these past two weeks have been exhausting, it’s incredibly rewarding to see how dedicated everyone is. The energy, teamwork, and commitment of the crew to ensure the success of this campaign have been truly inspiring. Each day, we’re making progress, and I can’t wait to see where the next days will take us.

Stay tuned as we continue our journey with the AVUELO campaign!

AVUELO has encountered one of the wettest and cloudiest dry seasons in memory. After a series of great acquisitions over core and important areas, our airborne science has stood down for several days with heavy cloud cover. So, what do AVUELO and a Joni Mitchell song have in common? She sings in “Both Sides Now” about how beautiful and enchanting clouds are but concludes:

“But now they only block the sun

They rain and they snow on everyone

So many things I would have done

But clouds got in my way”

They haven’t snowed on us in Panama, but they have definitely gotten in our way. Unusual weather, possibly associated with weak La Niña conditions, is resulting in more moisture transport to Panama and Costa Rica and fewer opportunities for flights, though AVUELO’s core areas and critical sites are largely covered. While the aircraft has been in the hangar, the team has met for no-go and planning meetings each day, and the field teams continue to obtain samples at a steady pace.

During the past few days, canopy trees at several sites, including from tall mature forests and younger stands, as well as samples from mangrove forests, have all come into the lab. Sampling and processing continue even as the aircraft waits for better weather.

Each Friday, the Gamboa-based team hosts a Friday seminar. This past Friday, Andres Baresch presented on pantropical trait retrievals from a partner instrument, PRISMA, from the Italian Space Agency, reprising a talk in Spanish given earlier at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute (STRI) Panama City HQ, well attended by many STRI scientists working on a range of projects.

A few days ago, Project Scientist Erika Podest and I, with Helena Muller-Landau, AVUELO’s lead scientist from STRI, took several staff from Panama’s Environment Ministry to Barro Colorado Island (BCI). We had an amazing tour of the site where AVUELO was sampling and saw samples being collected from the canopy by skilled forest rangers. We had the chance to see wildlife, birds like the slaty tailed trogon and tinamou, forest deer, and both howler monkeys (well-named) and shy spider monkeys.

While we were at Barro Colorado, we participated in a NASA Jet Propulsion Laboaratory (JPL) project. Artists at the lab create disks with the name of a field location in Morse code. When a JPLer is at a field location, they press the disk into the ground, and it creates a transient memorial, which we can photograph as part of a collection. Erika and I found a muddy spot by a stream where the soil was soft enough to take the impression and then had to decode the Morse to tell the Barro Colorado disk from a Panama City disk. We pressed it in and took photos, linking BCI, STRI, and JPL in Panama through our collaboration.

To scientists accustomed to temperate forests, the diversity of the tropical forest is overwhelming, as one rarely encounters the same species twice. These forests present an entirely new challenge to imaging spectroscopy, and the precisely located foliar analyses together with coordinated aircraft observations will open a new world of analysis for Earth Observations, with current and ever more spectroscopic missions on orbit to document the changing function of tropical forests with pressure from climate and land use. Knowing there could be hundreds of species per hectare in Panama (more types of trees than in all of North America) was different than seeing the forest and different from seeing the huge variety of leaves passing through the lab.

As I write this, AVUELO is pivoting to marine observations along Costa Rica’s west coast, supported by a new crew, ocean biologists from Costa Rica, and members of NASA’s PACE instrument team, observing the diversity and unique aspects of the tropical ocean. They will report in soon! But, in Panama, for now, we are eager for another one of Joni Mitchell’s song lyrics, “Come to the Sunshine.”

It’s really hard to believe, but I will already be departing Panama tomorrow. When I arrived a week ago, on February 5, I had a hunch but didn’t fully appreciate just how busy our AVUELO ground and airborne teams would be keeping up with our ambitious sampling and data collection plans and schedule. For me personally, getting to participate in the campaign was exciting because it meant a continuation of my past tropical forest research in Panama, which included similar sampling and objectives at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute’s (STRI) crane sites and on Barro Colorado Island.

I had some expectation of how long and challenging the field days would be, especially when they are repeated for multiple days in a row. Yet for AVUELO, the sheer scale and scope of logistical coordination across multiple teams and locations, instrumentation, and lab analyses have been impressive to witness, including how well the whole team has stepped up to meet the challenges and the correspondingly long days in the field and lab. The whole team has come together to support the goals and interests of everyone involved, and it’s been humbling to witness how quickly the team gelled and really became a “well-oiled” machine. I will surely miss helping with sample processing after I depart!

Thinking back, our first field day at the Smithsonian Parque Natural Metropolitano canopy crane resulted in far more samples to process in the lab than we expected. Despite some remaining uncertainty and a late start on our first sampling day, the team quickly found their sample collection groove and continued the same basic approach until our final sampling day on February 11. Over our time here, the incredibly skilled STRI crane operators, Edwin Andrade and Oscar Saldaña, made sure we could access and collect the samples we needed with ease in order to link with the remote sensing data. We even had some extra help from the forest locals.

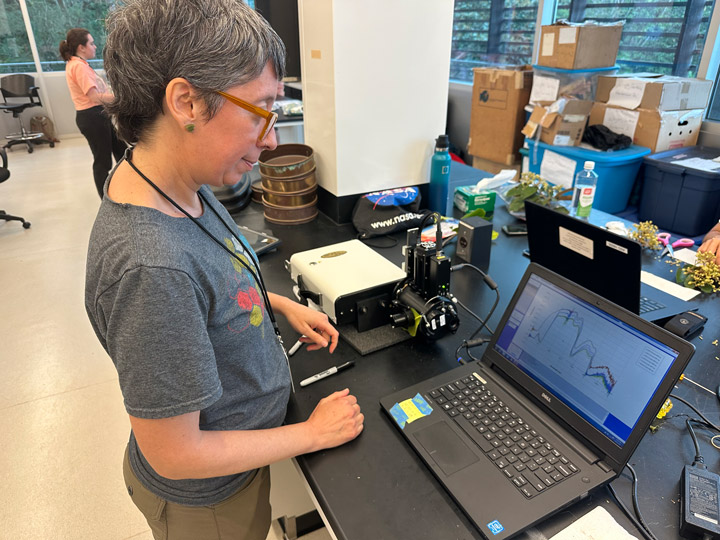

In the STRI labs in Gamboa, folks have been busily processing the samples coming in from multiple sites across Panama to try and keep up with field teams. As is common at this point in a campaign, the lab mimics an assembly line, with samples rapidly moving between stations to measure leaf area, leaf water content, and leaf optical properties, as well as prepare samples for other analytical measurements to happen at a later time. Given AVUELO is a hyperspectral remote sensing campaign, we had to have our spectrometers in the lab to measure leaf-level reflectance and transmittance (photos below). With these data, we are building a very comprehensive spectral library that we will use to estimate foliar functional traits and to inform tropical scaling and spectral modeling research.

AVUELO also represents a multi-year dream of mine to be able to link years of field campaigns in Panama to AVIRIS imagery. It has been incredible to finally see NASA AVIRIS imagery over these sites in Panama, where scientists have already been building a data record for more than a century.

We have been lucky enough to have multiple flight days already, and I am hopeful there will be more, but the data already collected will provide incredible new research opportunities. I am looking forward to working together to develop the products and datasets the community can use to conduct novel science and make new discoveries!

Despite just how busy we all have been, we also had time for other activities. On February 7, Natalia L Quinteros Casaverde, a postdoctoral research associate at NASA Goddard, provided a seminar in Spanish during the STRI seminar series.

Those in attendance had many great questions, and it’s clear this campaign is generating a lot of interest from the community, and our team is eager to help support the use of the data! We also had time to visit Casco Viejo (photo below), though I never did have a chance to jump in the hotel pool. It’s bittersweet to head home, but I look forward to working with the team on data analysis and maybe even coming back to Panama soon to visit, conduct science, and continue to contribute to the rich history of tropical forest research. So long, and thanks for all the leaves!

On February 6, 2025, after years of preparation and four months of intense planning, an aircraft with an advanced NASA instrument took off for the AVUELO campaign’s first survey in the tropics, while teams on the ground spread out to collect ground-truth data. The Airborne Validation Unified Experiment: Land to Ocean (AVUELO) is a partnership between NASA, the Smithsonian Institution’s Tropical Research Institute, and the Costa Rican Fisheries Federation, as well as universities and institutes in the United States and Panama.

AVUELO’s goal is to calibrate a new class of space-borne imagers for tropical vegetation and oceans research. These data will eventually help us understand how the thousands of tree species and marine organisms create unique ecosystems.

Day one, though, was a nail-biting, adrenaline-fueled day as we waited to see if plans for aircraft flights and the coordinated fieldwork would come together or whether the team would go back to the drawing board. Many members of the team had done similar projects in many regions, but each airborne project has its own unique features.

The weekend before, the teams had been thrilled to watch maps on the flight tracker as the twin-engine turboprop aircraft left California for Texas, then stopped in Mexico for fuel, and ultimately arrived in Panama.

On January 6, after the teams arrived for the fieldwork, we had a preflight phone call and agreed on a plan. About 20 scientists collected and measured leaves, while other crews analyzed samples in the laboratory. The aircraft took off and began methodically collecting data over the core study area, a 25- by 50-mile block along the Panama Canal basin, which has dense rainforests, coastal mangroves, rivers, and lakes.

We watched on the flight tracker as the plane perfectly executed the planned flight, hoping for the weather we needed. We were thrilled as field teams returned with numerous successfully and arduously collected leaf samples. An hour or so after the aircraft landed, the team looked at previews of the imagery collected. Despite some clouds in the scenes, most of the key sites were clear, and with this data, the project was off to a successful start. The fieldwork will continue for another month as teams work to fully achieve AVUELO’s scientific objectives.

The day’s accomplishments were satisfying in a cool, calm scientific way, knowing we had started collecting the data that could transform our understanding of tropical forests, while knowing the road to get here was long. It was viscerally thrilling to have a successful first day after months of intense planning and challenges to overcome, which included coordinating arrivals from multiple universities and centers and organizing housing, safety plans, and communications between the aircraft aloft, crews on the ground, and boats in the ocean.

When the previews of the data appeared and we knew we had a successful first day, it was like a weight was being removed. It was time for a celebration!