2019 is bound to become one of the largest fire years on record in the Arctic Circle, and especially in Siberia. How much carbon these fires release remains a challenging question. Very little ground data on fire emissions is available for Siberia and estimations are difficult since the main part of the emissions originates from organic soils, which is harder to retrieve from satellite imagery than emissions from aboveground biomass. Our research team from the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam (the Netherlands), Woods Hole Research Center, Northern Arizona University (USA), Pyrenean Institute of Ecology (Spain), and the Siberian Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences and Tomsk State University (Russia) are joining forces to better understand fire dynamics in Siberia.

After an adventurous three-hour drive, our field crew gathered with the local collaborators at Kajbasovo Research Station near Tomsk, in Russia. We aimed at finding old pine trees in burned and unburned sites, which we then core with tree borers to build tree-ring chronologies. Wildfires in this western part of the Siberian boreal forest usually don’t burn with high intensity allowing some resilient trees to survive multiple fire cycles. Thus, we aimed at using the chronologies to reconstruct the fire history of the area and to assess the response and recovery times of the ecosystem after fire events and other disturbances.

Little did we know that we would ourselves witness the severity of this year’s fire season. Except for the first day, we did not see a clear sky. From then on, the sun would only appear as a bright orange or blood red ball behind lots of smoke originating from wildfires in the Krasnoyarsk region hundreds of kilometers away. One good thing about this is that it dampened the heat, since we were already quite warmly dressed in our tick- and mosquito-proof clothing.

Mosquitoes and heat, however, were only small obstacles, as we set out with our borers to find trees older than 100 years. We really wanted trees from that age so that we can build sufficiently long chronologies. Even at the most remote places we were surprised to often see signs of human activity such as past logging, resin extraction or littering. One day we even saved a duckling out of a fisher net set up a good 4 hours bumpy drive away from the next village. Or sometimes we would simply not find old trees because of natural disturbances or growth restrictions. Eventually, we did manage to sample 12 sites with old trees with different fire severities and hydrologic characteristics. These will now be analysed further in the lab to extract and crossdate the tree rings.

Being in the field and having only very little time to sample can be an intense working experience, but there were many special little moments too. Our driver overcame every obstacle on the way to bring us to very remote places, and our cook took great care of us with plenty of delicious borscht, buckwheat and blinis (type of pancakes) and provided large amounts of water and kompot (sweet fruit beverage). And our evenings were spent at camp fires diving into local culture and connecting the people.

After ten exciting days in Tomsk we are now resting and recovering in Yakutsk for the weekend. We are using the time for some team building activities, and we are enjoying some solid hours of sleep. We went shopping for supplies for the second part of our field campaign, which will lead us to even more remote areas around the little villages of Ert and Batamay in the next four weeks. There, we will visit recently burned forests and measure the carbon losses due to fire events. In addition, we will take more tree chronologies to estimate the stand age, and count seedlings to see how forests recover after fires of different severities.

This field campaign is part of the ‘Fires pushing trees North’ project funded by the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO) and affiliated with NASA ABoVE. The Tomsk part of the campaign was funded by INTERACT.

This blog post was written by Rebecca Scholten, PhD student at Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, researching arctic-boreal fire dynamics.

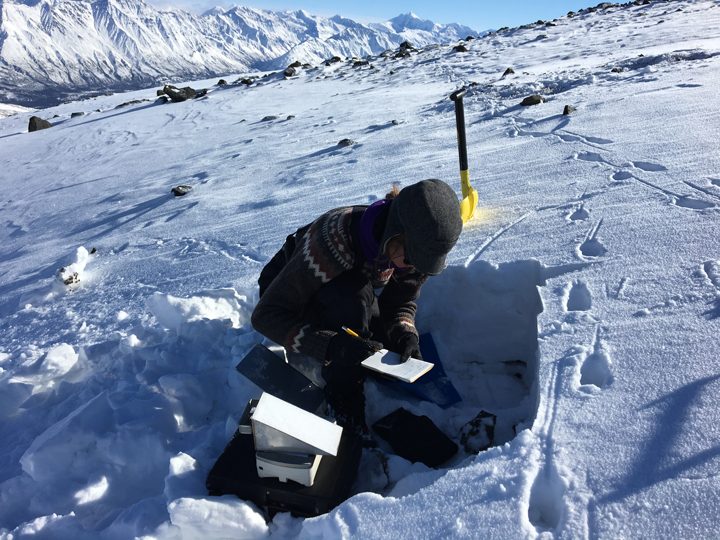

On March 14, four members of the NASA ABoVE Dall sheep project (lead PI Laura Prugh and PhD students Chris Cosgrove, Ryan Crumley, and Molly Tedesche) headed into the Wrangell Mountains for a week-long field expedition to conduct snow surveys. These snow surveys are critical to the project’s goal of understanding how snow conditions are changing and affecting Dall sheep in northern alpine regions. Riding snowmobiles for more than 20 miles into the wilderness, breaking trail and clearing brush for the last 5 miles (and sometimes getting stuck), the crew set up base camp in an open meadow. It turned out this meadow was home to a resident bull moose, who kept a respectful distance and was often seen browsing nearby. Snow levels were unusually high this year, making for a useful contrast to last year’s surveys and giving team members a good snowshoeing workout. Navigating through deep snow, thick brush, and over steep terrain, the team recorded snow depth using a Magnaprobe, dug snow pits to examine the snowpack stratigraphy (layering over the season), and measured snow track sink depths of Dall sheep and one of their main predators, coyotes. The team was able to reach 17 of the 22 sites that had been established in September to record snow depth every hour using game cameras and snow stakes; the remaining 5 sites were in terrain that was unsafe to reach due to avalanche danger.

The team’s luck with clear, warm weather broke on the last day of fieldwork. Amid a snowstorm that was picking up momentum, Prugh spotted an area with a maze of coyote tracks and what appeared to be the faint traces of white fur on the snow. Investigation confirmed the site was a sheep kill, and Prugh quickly dug a pit to record the snow characteristics that may have contributed to the sheep’s demise. Perhaps the snow was dense enough for the coyotes to run on top of the snowpack, whereas the sheep, with a heavier body mass and small hooves, floundered in the deep snow?

Fortunately, the snowstorm ended overnight, and the crew awoke to blue skies overhead and 8 inches of fresh powder blanketing the spectacular landscape. Analysis of the field data over the coming year will improve efforts to model and map snow characteristics across the mountainous region, and reveal how snow properties affect the vulnerability of Dall sheep to predation.

PhD student Chris Cosgrove (Oregon State University) measures snow density adjacent to Dall sheep snow tracks.

PI Laura Prugh (University of Washington) using a Magnaprobe to measure snow depth.

Winter camp in Wrangell St. Elias National Park. Snowmobiles, Arctic Oven tent, and winter camping gear was provided by the ABoVE Fairbanks Logistics office.

Snowmobiling expedition in the Wrangell mountains to conduct snow surveys.

Arctic landscapes (shown above) hold our planet’s largest pool of soil carbon, which has been stored for thousands of years in frozen ground known as permafrost. This large store of carbon is now susceptible to release into the atmosphere as greenhouse gases, as the once frozen ground begins to warm. Scientists with the NASA Arctic Boreal Vulnerability Experiment (ABoVE) are currently working to find out how the Arctic carbon pool is responding to climate change and whether the Arctic is acting as a carbon sink or carbon source. Photo by Jennifer Watts.

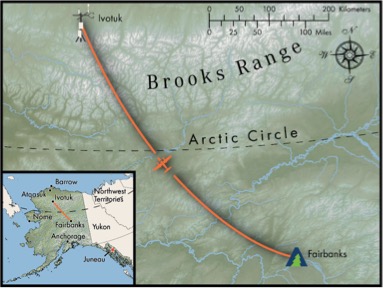

To improve our understanding of how large stores of soil carbon and Arctic vegetation are responding to climate change, a team of scientists participating in the NASA Arctic Boreal Vulnerability Experiment (ABoVE) recently gathered in Alaska to take part in a remote field campaign. Team members were Jennifer Watts (University of Montana; Woods Hole Research Center), Kyle Arndt and Andrea Fenner (San Diego State University), and Stephen Shirley (University of Montana). The objective of this campaign was to install a network of soil moisture and temperature sensors within the footprint of an eddy covariance flux (EC) tower located in Ivotuk, Alaska (Ivo-US, N 68.49 W -155.75). The EC tower measures carbon flux, or the direction and magnitude of carbon dioxide (CO2) and methane (CH4) gasses carried in turbulent surface winds, rolling across a roughly 1-km swath of land. These data are used to characterize and model ecological processes such as vegetation productivity, soil decomposition and respiration, and the net land-atmosphere carbon flux over Arctic/boreal regions.

This story documents our journey above the Arctic Circle and provides a description of our daily life while working in the Alaskan tundra.

Tuesday July 18, 2017 (Day 1)

Waking up early for a busy day of planning and packing, we departed our dorm rooms at the University of Alaska, Fairbanks and headed for the ABoVE Logistics Office to meet Logistics Coordinator Sarah Sackett. Sarah assisted us with gathering camping equipment and gave us a detailed tour of the field kitchen, shelter, and bear safety supplies. The day was spent packing equipment into drybags and Action Packers, and ensuring that we had all of the tools necessary to perform our work in Ivotuk.

Jennifer Watts and Kyle Arndt plan the installation of the soil moisture sensors. Photo by Stephen Shirley.

That afternoon, we went to the store to buy our camp food: Thai noodles, taco and grilled cheese supplies, pancake mix… the list goes on but needless to say we were going to eat well. We arrived back to the office late in the evening, just in time for dinner. All of the NASA ABoVE project members currently in Fairbanks had come to meet at the Logistics Office for a barbeque, and we didn’t want to miss out on the food and company. After enjoying a great evening, and focusing on final packing, we went to our dorms to get some rest and prepare for our early morning expedition to Ivotuk.

NASA ABoVE science team members gather for a photo at a 2017 Field Campaign cookout in Fairbanks. Photo by Charles Miller/NASA.

Wednesday July 19, 2017 (Day 2)

A map of our path from Fairbanks to Ivotuk. Photo by Stephen Shirley.

With a truck full of equipment, we departed the ABoVE Logistics Office for Wright Air Service in Fairbanks. Our dual engine Piper Chieftain could accommodate a maximum cargo weight of 1,400 lbs, including personnel and equipment. First we weighed ourselves and then our gear, which amounted to 200 lbs. over the weight limit. After dumping out all of our water, a spare GPS mapping unit, and some EC tower calibration equipment, we were able to board the plane.

Weighing our field and camping equipment to ensure that the plane wasn’t too heavy to take off. Photo by Stephen Shirley/NTSG.

Kyle Arndt, Stephen Shirley and Andrea Fenner, ready to fly to Ivotuk. Photo by Jennifer Watts.

We arrived in Ivotuk just before 10:00 and were greeted by swarms of mosquitos and scattered clouds. Our first priorities were setting up the bear fence surrounding our field camp, followed by the kitchen and personal tents, and finally filtering our first batch of water (since we had dumped our drinking water earlier that day). We then unpacked field equipment and headed across the tundra to the tower.

Unpacking gear upon landing in Ivotuk as our plane prepares to leave. Photo by Jennifer Watts.

Jennifer Watts sets up a GPS base station at the corner of the landing strip (far left), under a rainbow, next to our Ivotuk campsite. Notice the flying object, one of many mosquitoes, in the foreground. Photo by Stephen Shirley.

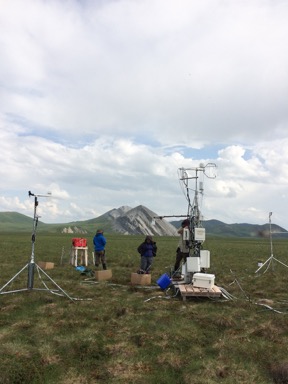

Kyle Arndt (right) makes room on the EC tower to hang the new datalogger box while Stephen Shirley and Andrea Fenner take in the scenery. Photo by Jennifer Watts.

Jennifer Watts and Andrea Fenner lay out soil moisture and temperature sensors. Photo by Stephen Shirley.

By late afternoon we had attached the datalogger box to the EC tower and were laying out the 18 soil moisture sensors of various lengths. Unravelling and walking out the 10 to 90 m cables was more challenging than anticipated. With the equipment box attached to the tower and sensors ready for installation we made our way to the power shed to charge our tools and equipment. Hungry and ready for bed, we made the rainy walk (the first of many) back to camp and tucked into our sleeping bags for the night.

Thursday July 20, 2017 (Day 3)

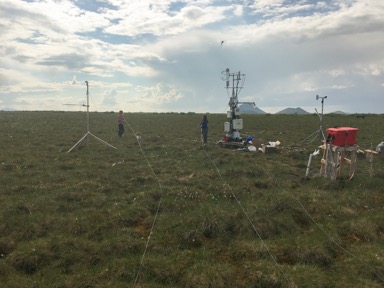

The majority of our Thursday was spent installing soil moisture sensors, three per site at 0-5 cm, 20 cm and 40 cm depths. Soil samples were collected for each site. We also measured the depth of the seasonally thawed soil layer overlying permafrost and the amount of water in the surface soils. Digging through frozen soil (in the rain) proved challenging. Sites with shallow thaw depths were even more work. First, we removed the thawed soil. Then we shoved out the frozen soil layer in little chunks, similar to scooping ice cream. Digging through the frozen soil for 10 cm or more took a lot of time and energy. After a late dinner, with our installation complete, we took an evening trip to the power shed to finalize the datalogger programming.

Jennifer Watts digs through frozen soil and muddy water to install soil moisture and temperature sensors. Photo by Stephen Shirley.

Stephen Shirley measures the active layer depth, the zone of thawed soil, above the permafrost. Photo by Jennifer Watts.

Andrea Fenner, Stephen Shirley, and Kyle Arndt run sensor cables into the datalogger box. Photo by Jennifer Watts.

Friday July 21, 2017 (Day 4)

After breakfast, we split up into groups for an independent science day. Kyle and Andrea took advantage of the sunny morning (the first since our arrival in Ivotuk) to take spectral measurements of the vegetation within the EC tower footprint. The spectral measurements are used to calculate various vegetation indices. Kyle and Andrea also collected samples of vegetation biomass to form a relationship between indices and above ground biomass. The biomass samples and spectral data may shed some light on the relationship between the plant biomass and methane fluxes emitted from the tundra.

Kyle Arndt collects vegetation biomass samples to accompany the spectral measurements. Photo by Andrea Fenner.

Jennifer and I spent our day collecting water samples from the braided tundra streams and small ponds located near the tower site. Water and gas samples were obtained at multiple locations for each water body. These samples will be analyzed for methane concentrations and isotopes to determine the amount and age of methane in the water bodies, which can be a major source of greenhouse gas emissions. The process took quite some time and we didn’t get done with the first two streams until late afternoon.

Jennifer Watts gathers water and gas samples from streams to determine methane concentrations. Photo by Stephen Shirley.

Late in the afternoon while Jennifer and I were finishing our second set of stream samples, Kyle and Andrea radioed that the cooking tent was about to fly away. Stormy weather was moving in. When I arrived at camp I saw Kyle and Andrea doing their best to hold down the tent. Our campsite was a mess. Everything had been blown around, inside and out, by the wind. We lost some time reorganizing our equipment and supplies, and securing the other tents. The rest of the evening was spent tying up loose ends on the independent projects, finishing stream samples and taking GPS points for Kyle’s measurements. After a late dinner, we made our daily trip to the power box to send emails and confirm that our flight out had been scheduled for the next day.

Kyle Arndt holds down the main tent after it was almost blown away by the wind; what a mess. Photo by Stephen Shirley.

Saturday July 22, 2017 (Day 4)

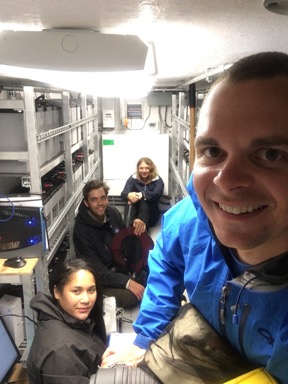

Sunday morning, we woke up to a wet and windy Ivotuk. To make things worse, the Ivotuk Hills and surrounding landscape were obscured by fog. After packing up science equipment, the kitchen and personal gear, we trekked across the misty tundra to the power shed to check emails and wait for updates on weather and the status of our chartered flight back to Fairbanks. We called Wright Air Service around 13:00 to report the best weather conditions that we had seen all day.

Jennifer Watts, Kyle Arndt, Andrea Fenner, and Stephen Shirley enjoying quality time in the power shed, possibly the driest place in Ivotuk. Photo by Stephen Shirley.

Our fingers were crossed that the sky would remain clear and that we wouldn’t have to spend another night in the wind and rain. Just about the time we had finished packing up our campsite, the plane arrived to take us home. The plane ride back was quiet. Everyone was tired and focused on the many tasks still ahead of us.

Stephen Shirley Jennifer Watts, Kyle Arndt and Andrea Fenner celebrating the end of the Ivotuk sensor install and the arrival of the plane to Fairbanks. Photo by Wright Air Service Pilot.

The next day would be spent downloading GPS information and preparing soil samples, taken for the calibration of our soil probes, for processing at the University of Montana. After replenishing supplies Jennifer, Kyle, and Andrea prepared to travel north to Barrow. Andrea would remain in Barrow while Jennifer and Kyle continued to Atqasuk for the next soil moisture sensor installation.

Over the course of my two weeks with the NASA ABoVE 2017 Field Campaign, I traversed the mucky tundra, dug holes through permafrost for the installation of soil moisture sensors, measured permafrost active layer and water table depths, and collected stream water samples around the Ivotuk airfield. This experience has improved my understanding of the Arctic tundra’s high spatial variability and the challenges faced when modeling its ecosystem processes at larger scales. The new measurements from the soil moisture sensor arrays installed in Ivotuk and Atqasuk this summer will help ecological modelers to quantify these small-scale differences for use in future biophysical land models.

Stephen Shirley is a senior undergraduate of Physical Geography and Research Technician at the University of Montana.

We created some interesting patterns reminiscent of alien crop circles during our snow surveys in Alaska’s Wrangell St Elias National Park last month. Anne Nolin, Chris Cosgrove, Kelly Sivy and I were flown to the Jaeger Mesa cabin in an R44 helicopter, and from there we spent a week measuring snow depth and density along transects, in spirals, in snow pits, and even in sheep tracks. We also checked on the cameras and snow stakes that we had deployed in September, and we were pleased to find all of them undisturbed, with just one camera out of 22 that malfunctioned. Snow survey data and photos of snow depth from the cameras will be used to ground truth a model of snow properties, which in turn will be used to understand how changing snow conditions affect Dall sheep movements.

A spiral is an efficient pattern that yields hundreds of snow depth measurements in a given area.

How hard does the snow have to be to support the weight of a sheep? We set out to answer this question by taking snow density measurements at 44 sets of sheep tracks and measuring the hoof dimensions and sink depth of the tracks. Although we are still examining the data, a quick visual examination shows a density threshold near 320 kg/m3, above which the sheep tracks remained on the snow surface (sink depth < 4 cm). These measurements will help us to understand how snow properties affect the energetics of winter travel and foraging (pawing through snow) for Dall sheep.

Laura Prugh using a Magnaprobe to record snow depth measurements. Not much snow here!

Anne Nolin using the Magnaprobe—quite a bit more snow on the leeward side.

Kelly Sivy measuring snow density and sheep track sink depths.

Ewes and lambs near one of our sampling transects.

Cratering, where sheep have pawed through the snow to forage on grass.

Spring has finally arrived in northern Alberta! The snow has melted, the skies are clear, and migration is in full swing. After several days of heavy snows and cold temperatures, the robins, and many other species, were in a big hurry to make their way north to their breeding grounds. Early in the mornings we saw huge numbers of birds flying overhead. In thirty minutes Nicole counted almost 5000 robins flying north! Because the robins were in such a rush to find a suitable place to set up a breeding territory they were not interested in stopping on our field to forage. This meant our best shot at catching robins was to catch them at sunrise or sunset when they were fueling up just before their daytime or nighttime travels.

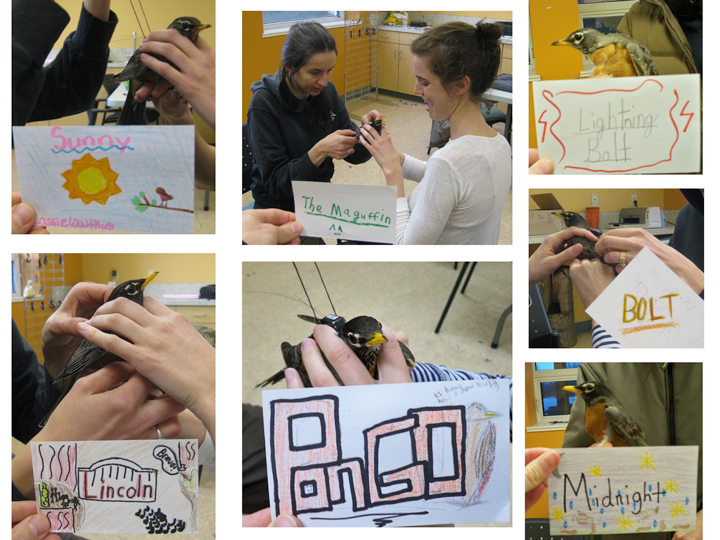

A flock of robins at sunrise.

At the peak of summer, the sun hardly goes down in the boreal forest and there are only a few hours of darkness at night. As summer grew closer over the course of our trip, sunrise got earlier and earlier and sunset got later and later. As a result, the robins, and Nicole and I, were waking up earlier and going to bed later. We found 6 Space Robins first thing in the morning: Lightning Bolt, Lincoln, the Maguffin, Pongo, Sunny, and Bolt. We found one of our Space Robins just as we were going to close our nets for the night and we very appropriately named him Midnight. Here are our final Space Robins!

As the boreal forest transitioned to spring, we got the chance to catch a glimpse of some more tracks in the remaining snow. These tracks were bigger than the coyote tracks we spotted before. Can you guess who might have made these tracks?

Wolf tracks! These paw prints were about the size of my palm.

Nicole told us that a wolf had been spotted nearby and that a pack is known to live in the area. In the winter, the wolves like to use the frozen lake as a highway for covering ground quickly. Hoping to catch the wolves in action we set up a wildlife camera on the walking trail near the lake. Unfortunately we did not capture the wolf, but we did see a coyote!

Setting up the wildlife camera.

Dan, a friendly sasquatch, in front of the frozen lake.

Possibly because of the heavy spring snows, migration happened very quickly this year. The largest groups of robins moved through the area in just two days and very few decided to forage on our field. The large flocks of robins flying overhead were amazing to watch, but it meant that we were not able to capture our final two robins. We did see plenty of other species migrating, and so I would like to introduce two honorary Space Robins. Even though they won’t be wearing backpacks we did spot two Bald Eagles who seemed worthy of Space Robin names. Meet Soarin and Flounder Jr.!

We had a blast finding our 28 Space Robins, but now that they are flying for us the real fun begins. Each of our robins will provide valuable information on their migration route and how they respond to the environment. I’m excited to start untangling this migration mystery. Thanks so much for following along!

We had a blast finding our 28 Space Robins, but now that they are flying for us the real fun begins. Each of our robins will provide valuable information on their migration route and how they respond to the environment. I’m excited to start untangling this migration mystery. Thanks so much for following along!