Editor’s Note: We have highlighted the story of the Pilgrims and Thanksgiving several times over the years. Here are some of those pieces in one convenient place.

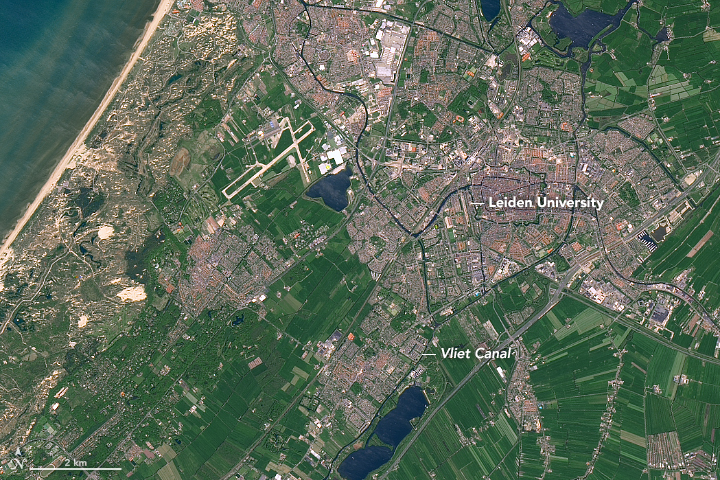

First stop, Holland. Image credit: NASA Earth Observatory image by Joshua Stevens, using Landsat data from the U.S. Geological Survey.

Most school children in America learn about the Pilgrims—the group of English settlers who endured a harrowing journey to the New World in 1620 on the Mayflower. It is sometimes overlooked, however, that Plymouth was not the first stop—nor the intended destination—for this congregation of religious separatists from the town of Scrooby in the English county of Nottinghamshire.

Before ever setting foot in North America, the Pilgrims spent several years living in Leiden, a city in the Netherlands. Most of the hundred or so people in the congregation lived in one-room cottages near Leiden University, in the shadow of the Pieterskerk, the oldest church in the city.

About a decade after they arrived, the congregation decided it was time to move. Tough economic conditions in Leiden meant few new recruits from England were willing to join them; Dutch culture was thought to be a bad influence on the children; and there was a looming possibility that Holland would go to war with Spain, a leading Catholic power.

Leaving Leiden University. NASA Earth Observatory image by Joshua Stevens, using Landsat data from the U.S. Geological Survey.

Leiden was a city of many waterways, so when the Pilgrims were ready to leave in July 1620, they boarded several small boats on the Rapenburg Canal (near the university). This narrow canal fed into the larger Vliet Canal, which flows from Leiden toward Delft.

From there, they made their way back to England, where they struggled for a few months trying to repair a leaking ship. After abandoning that ship, they finally set sail for the New World on September 6, 1620, knowing they had to cross nearly 3,000 miles of open ocean.

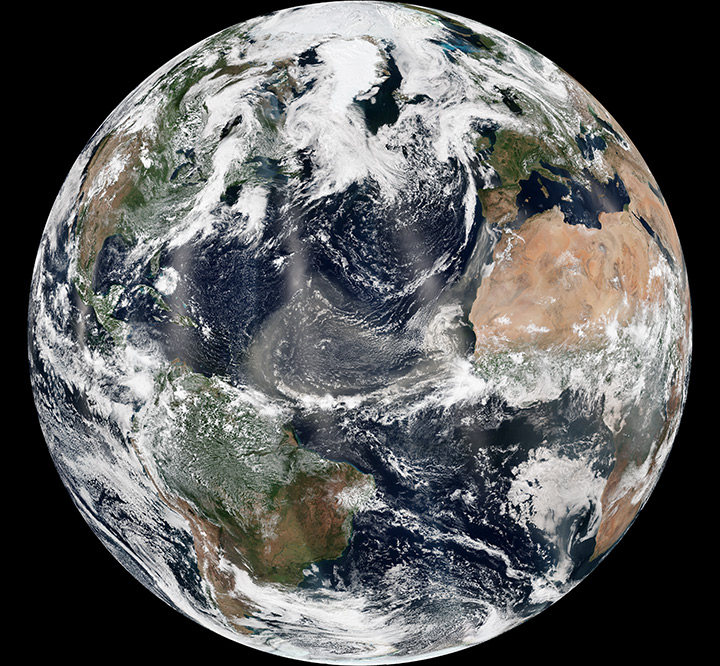

The North Atlantic can be treacherous. Image credit: NASA Earth Observatory image by Jesse Allen and Robert Simmon, using VIIRS data from the Suomi National Polar-orbiting Partnership.

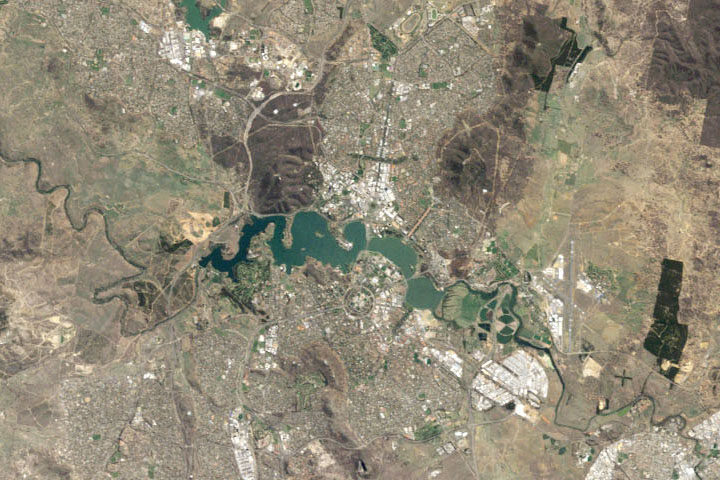

The original destination: the mouth of the Hudson River. NASA Earth Observatory image by Jesse Allen, using Landsat data from the U.S. Geological Survey.

The first half of the two month journey proved to be smooth and uneventful. But in October, they encountered a series of storms that turned the sea into a writhing cauldron. During one particularly bad storm, the ship nearly capsized.

Their intended destination was the northern edge of Virginia Colony, which at the time stretched from to the mouth of the Hudson River. However, the storms blew the Pilgrims off course toward Cape Cod in Massachusetts.

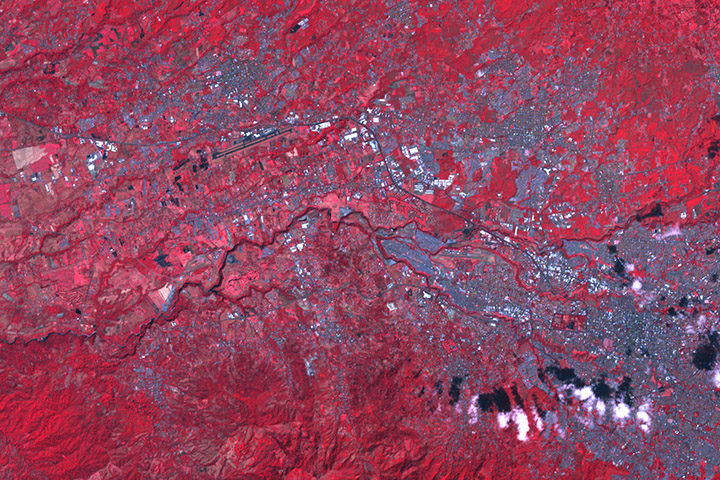

Provincetown, Massachusetts. NASA Earth Observatory image by Jesse Allen, using Landsat data from the U.S. Geological Survey.

When they realized this, they contemplated heading south. However, they were wary of the shallow waters and shoals east and south of Cape Cod and Nantucket—waters full of the sandy, rocky outwash from ancient glaciers. They sailed instead around the northeastern tip of the Cape and on November 21, 1620, dropped anchor just off the shores of modern-day Provincetown. While resting in that harbor, they composed and signed the first self-governing document in American history, the Mayflower Compact.

Over the coming weeks, they made first contact with Native American people, likely the Nauset tribe. First Encounter Beach in Eastham marks the reported location of a skirmish between the colonists and the tribe. The Pilgrims eventually sailed across Cape Cod Bay and settled in Plymouth.

First Encounter Beach. NASA Earth Observatory image by Jesse Allen, using Landsat data from the U.S. Geological Survey.

It was in Plymouth where the Pilgrims celebrated the first Thanksgiving, a three-day harvest celebration that included feasting, games, and military exercises.

While there continues to be debate among historians about the circumstances and influences that led to the first Thanksgiving, there is evidence that the roots of the tradition might be traced back to Leiden. During their time in the city, the Pilgrims would have experienced a celebratory thanksgiving service and festival that was held each year on October 3 to mark the 1574 end of the Spanish siege of the city.

Crossing Cape Cod Bay brought the Pilgrims to Plymouth. This astronaut photograph was acquired on November 7, 2007.

Betty Fleming, a cartographer, helped discover tiny Landsat Island with satellite imagery in the 1970s. Photo courtesy of Betty Fleming.

At age 86, Betty Fleming was on a cruise along the Labrador Coast of Canada. The ship was approaching an area all too familiar to her: a small island she helped discover when she was a cartographer for the Surveys and Mapping branch in Canada’s Department of Energy, Mines, and Resources.

“I want to tell you about a small off-shore island that we will be passing as we round the top end of Labrador on this trip,” wrote Fleming in her notes, which she used to deliver a presentation to her 90 fellow passengers on her leisure Adventure Canada cruise. “Landsat Island has garnered quite a bit of attention since it was first mapped in 1976. Don’t expect to see it though, as it is in the middle of an area of reefs and shoals.”

More than 45 years ago, Fleming was surveying the same waters, but via satellite imagery from the Landsat 1 satellite. Earth Resources Technology Satellite 1, later named Landsat, was an early Earth-sensing satellite launched by the United States. Before the satellite even launched, Canada built a receiving station to receive the satellite data for the orbits over Canada.

Aerial image of Landsat Island taken by David Gray on August 2, 1997.

This satellite image of Landsat Island captured on July 15, 2014, by the Operational Land Imager (OLI) on Landsat 8. The island spans no more than a pixel or two. Image credit: NASA Earth Observatory/Joshua Stevens

The 1970s was an exciting time for Fleming, as acquiring and analyzing satellite imagery was new and thrilling. As Canada received imagery from Landsat roughly every two weeks, Fleming had the task of seeing where the Department of Energy, Mines and Resources might use the imagery for mapping Canada, particularly for mapping wilderness areas and building new roads. At the time, the hydrographic charts for the northern coast of Labrador were also quite old and based on surveys by the British Navy in 1911 and on questionable notes made by passing sailors.

In those early Landsat days, Fleming was inspecting imagery of the coast from Landsat 1 when she spotted several small white specks. At first, she assumed they were icebergs, but some of the specks kept appearing in the same position over several images. She knew some of them had to be permanent features.

Landsat coverage of the survey area showing the overlap of the satellite images. The land area tended to be cloud-covered, forcing the selection of control points to the narrow coastal band as shown. Image courtesy of Betty Fleming.

She passed the information to the Canadian Hydrographic Survey Division, which sent the CCS Baffin to visit about 20 such locations in the following summer. Most of the locations were insignificant rocks partly submerged in the sea—Fleming called them “rocks awash”– but one of the spots was actually an island. Fleming and the Landsat satellite had discovered an uncharted Canadian island. It eventually became known as Landsat Island.

CSS Baffin survey of the coast of Labrador from 59°15’N to 60° 25’N during 1976 to chart offshore features and check reported rocks. Image courtesy of Betty Fleming.

Landsat Island was not too spectacular. It was rocky and only about half the size of a football field. From a satellite perspective, though, this island was notable because of its size – or rather lack of it. Earth science researchers were impressed that a satellite could detect such a small feature. The island was also interesting, says Fleming, because it had a bearing on the international boundary: it was the most easterly point of land at that part of the coast.

Fleming has never seen Landsat Island and does not expect to. She never went out on the ships or helicopters that were sent to verify the existence of the island. That section of the Labrador coast is “very dangerous,” and her tourist cruise in 2011 is probably the closest she is going to get to the place she discovered.

But that doesn’t faze her. Her accomplishments go beyond one island. Before her stint analyzing Landsat data, she was a pilot and camera operator. She studied at the newly formed Netherlands International Training Centre for Aerial Photography and Earth Sciences and became a specialist on the application of aerial photography to photogrammetric mapping—using photographs to measure and map areas. She also instituted a index map where images could be ordered by orbit number and image number, which was used in Canada.

Then there was simply being a working woman from the 1950s to 1980s, which Fleming says is a story in itself. As a married woman, she too-often ran into people who told her “You’ll leave to have a baby,” or “You’ll take a job from a man.”

When she chose to enter the all-male Surveys and Mapping Department, she had an entry level job at which they hired boys out of high school—despite the fact she had a university degree, post-graduate training, and experience in the aerial survey business. She always used the name “E.A. Fleming” when she prepared a technical paper because “using the name Elizabeth on any technical paper would have been a kiss of death. It would immediately be dropped in the editor’s waste basket without opening it.” She won several awards for her published papers, much to the chagrin of one man who did not find out she was a woman until she accepted an award.

“It took me 20 years to get to the level I should have been hired at, but that doesn’t change the fact that I really enjoyed my work,” wrote Fleming.

After a 30 year-long career in aerial photography and mapping and two happy marriages, Fleming is now retired at the age of 93 and resides in Ottawa, Canada.

Read more at:

The Island Named After a Satellite (NASA Earth Observatory)

Landsat Island (NASA Landsat Science)

The Telstar satellite (left) and the 1974 Telstar Durlast, the official ball of the 1974 World Cup. Image Credit: Bell Labs/Shine 2010

Goooooooal!!!! The 2018 FIFA World Cup kicked off on June 14, 2018.

Here’s a bit of Cup trivia you may not know. In 1962, NASA launched a small, spherical communications satellite called Telstar that ended up altering the look of the balls used in the World Cup.

Telstar was the first active communications satellite and the first commercial payload in space. By sending television signals, telephone calls, and fax images from space, the 3-foot-long satellite kicked off a whole new era in telecommunications—and soccer ball design.

There’s a direct line between the distinctive black and white patterning of Telstar’s hull and solar panels and the Adidas ball used as the official ball of the 1970 World Cup in Mexico and the 1974 World Cup in West Germany. While earlier generations of soccer balls were brown and did not show up well on television, the 1970 and 1974 balls featured the now iconic 32-panel design of alternating white hexagons and black pentagons, a pattern that closely resembled Telstar. Fittingly, that first ball was called Telstar Elast; the official ball in 2018, a nod to the 1970 ball, is called the Telstar 18.

To celebrate the World Cup, Earth Observatory is planning to dig into its archives. For key games, we’ll grab one image for each of the two countries going head to head. Can you guess which image goes with which country? Just click on the images below to find out. Enjoy the tournament!

June 14:

Russia 5 — 0 Saudi Arabia

June 16

France 2 — 1 Australia

June 17

Costa Rica 0 — 1 Serbia

Brazil 1 — 1 Switzerland

June 18

Sweden vs. Korea Republic