Every year, a group of scientists affiliated with the Global Carbon Project give Earth something like an annual checkup. Among the key questions they address: how much carbon is stored in the atmosphere, the ocean, and the land? And how much of that carbon has moved from one reservoir to another through fossil fuel burning, deforestation, reforestation, and uptake by the ocean each year?

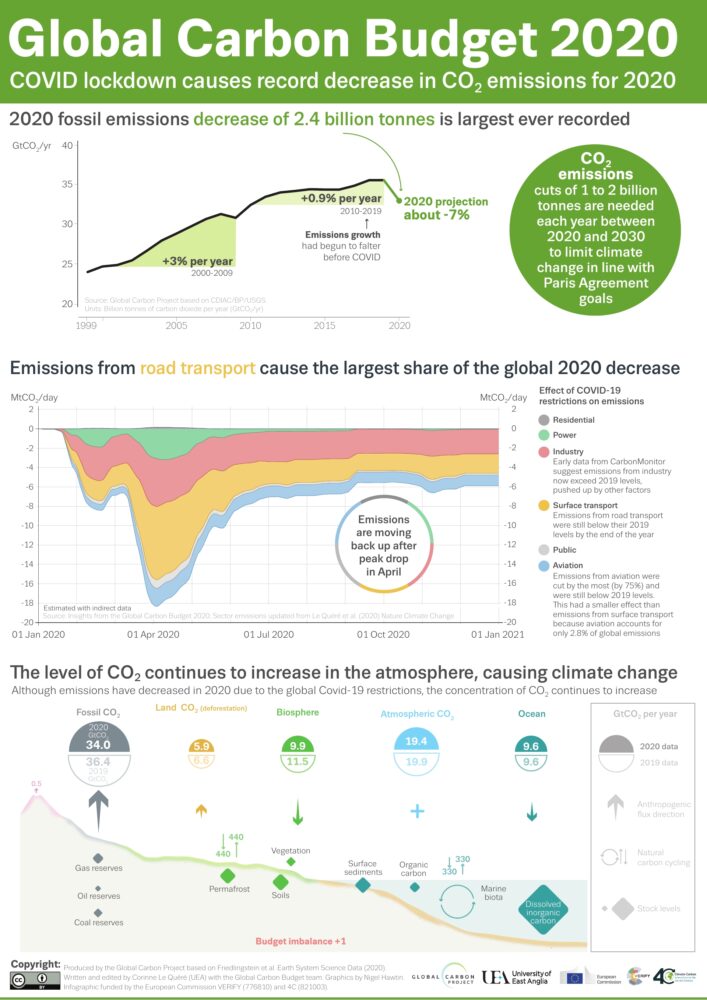

All of the latest findings—including the data for 2020, a year like few others—are available here, including links to dozens of interesting charts and a peer-reviewed science paper. Ben Poulter, a NASA scientist and member of the Global Carbon Project team, summarized the findings this way: “The economic effects of COVID-19 caused fossil fuel emissions to decrease by 7 percent in 2020, but we continued to see atmospheric CO2 concentrations increase, by 2.5 ppm, or about 5.3 PgC. This means that the remaining carbon budget to avoid 1.5 or 2 degrees warming continues to shrink, and that we need to continue to monitor the land, ocean, and atmosphere to understand where fossil fuel CO2 ends up.”

Below are 10 key findings from the most recent report. (Note: the Global Carbon Project team synthesizes a broad range of data, some of which requires time-consuming processing, quality-control, and analysis. While they do report some 2020 numbers, the most recent full year of data available for others is 2019.)

The Global Carbon Budget is produced by more than 80 researchers working from universities and research institutions in 15 countries. Observations from several NASA satellites, sensors, aircraft, and models were among the sources of information used to formulate the 2020 budget. Sources of information supported by NASA included: the MODIS sensors on Aqua and Terra satellites, the Global Fire Emissions Database (GFED), the LPJ land surface carbon exchange model, Landsat, the LUHv2 land-cover change model, the CASA land surface carbon exchange model, ODIAC fossil fuel emissions data, the MERRA-2 reanalysis, the Cooperative Global Atmospheric Data Integration Project, and OCO-2.

If you follow science news, this will probably sound familiar.

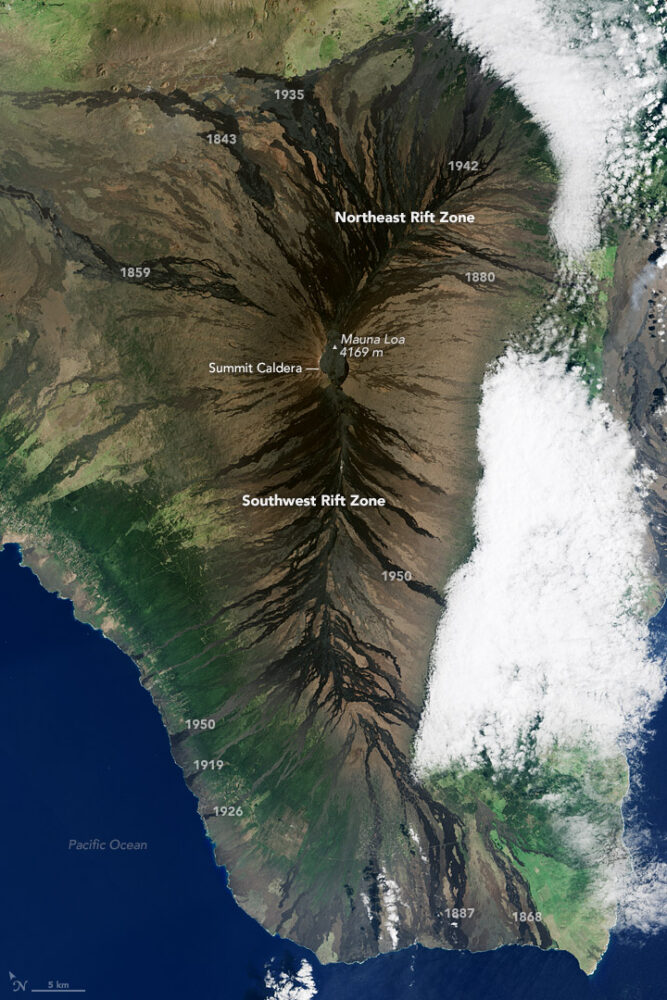

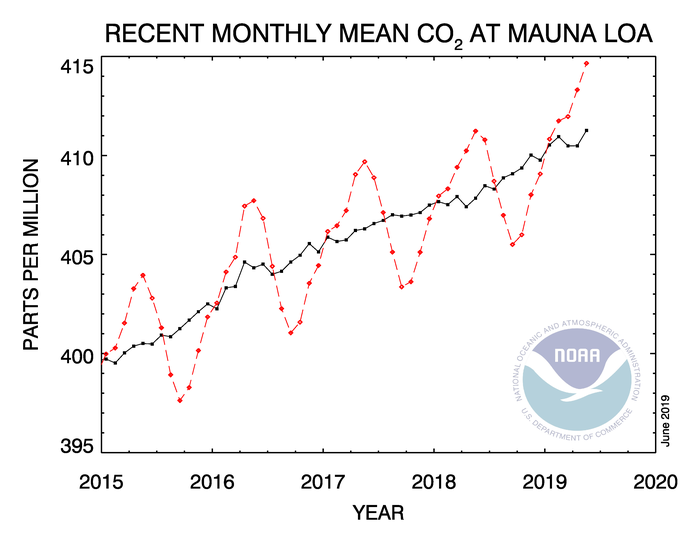

In May 2019, when atmospheric carbon dioxide reached its yearly peak, it set a record. The May average concentration of the greenhouse gas was 414.7 parts per million (ppm), as observed at NOAA’s Mauna Loa Atmospheric Baseline Observatory in Hawaii. That was the highest seasonal peak in 61 years, and the seventh consecutive year with a steep increase, according to NOAA and the Scripps Institution of Oceanography.

The Mauna Loa Observatory has been measuring carbon dioxide since 1958. The remote location (high on a volcano) and scarce vegetation make it a good place to monitor carbon dioxide because it does not have much interference from local sources of the gas. (There are occasional volcanic emissions, but scientists can easily monitor and filter them out.) Mauna Loa is part of a globally distributed network of air sampling sites that measure how much carbon dioxide is in the atmosphere.

The broad consensus among climate scientists is that increasing concentrations of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere are causing temperatures to warm, sea levels to rise, oceans to grow more acidic, and rainstorms, droughts, floods and fires to become more severe. Here are six less widely known but interesting things to know about carbon dioxide.

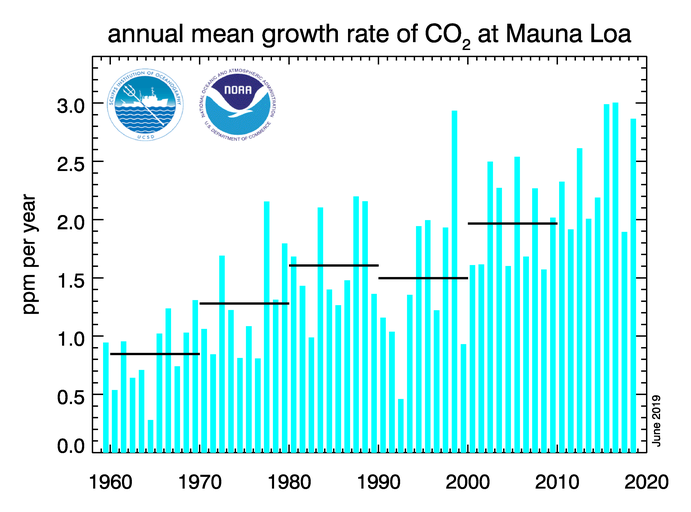

For decades, carbon dioxide concentrations have been increasing every year. In the 1960s, Mauna Loa saw annual increases around 0.8 ppm per year. By the 1980s and 1990s, the growth rate was up to 1.5 ppm year. Now it is above 2 ppm per year. There is “abundant and conclusive evidence” that the acceleration is caused by increased emissions, according to Pieter Tans, senior scientist with NOAA’s Global Monitoring Division.

To understand carbon dioxide variations prior to 1958, scientists rely on ice cores. Researchers have drilled deep into icepack in Antarctica and Greenland and taken samples of ice that are thousands of years old. That old ice contains trapped air bubbles that make it possible for scientists to reconstruct past carbon dioxide levels. The video below, produced by NOAA, illustrates this data set in beautiful detail. Notice how the variations and seasonal “noise” in the observations at short time scales fade away as you look at longer time scales.

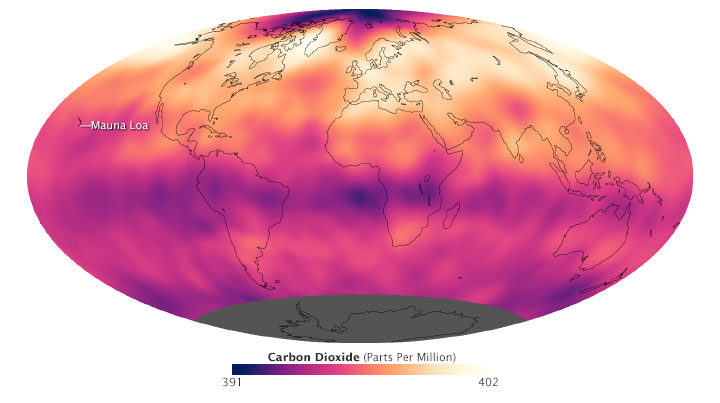

Satellite observations show carbon dioxide in the air can be somewhat patchy, with high concentrations in some places and lower concentrations in others. For instance, the map below shows carbon dioxide levels for May 2013 in the mid-troposphere, the part of the atmosphere where most weather occurs. At the time there was more carbon dioxide in the northern hemisphere because crops, grasses, and trees hadn’t greened up yet and absorbed some of the gas. The transport and distribution of CO2 throughout the atmosphere is controlled by the jet stream, large weather systems, and other large-scale atmospheric circulations. This patchiness has raised interesting questions about how carbon dioxide is transported from one part of the atmosphere to another—both horizontally and vertically.

In this animation from NASA’s Scientific Visualization Studio, big plumes of carbon dioxide stream from cities in North America, Asia, and Europe. They also rise from areas with active crop fires or wildfires. Yet these plumes quickly get mixed as they rise and encounter high-altitude winds. In the visualization, reds and yellows show regions of higher than average CO2, while blues show regions lower than average. The pulsing of the data is caused by the day/night cycle of plant photosynthesis at the ground. This view highlights carbon dioxide emissions from crop fires in South America and Africa. The carbon dioxide can be transported over long distances, but notice how mountains can block the flow of the gas.

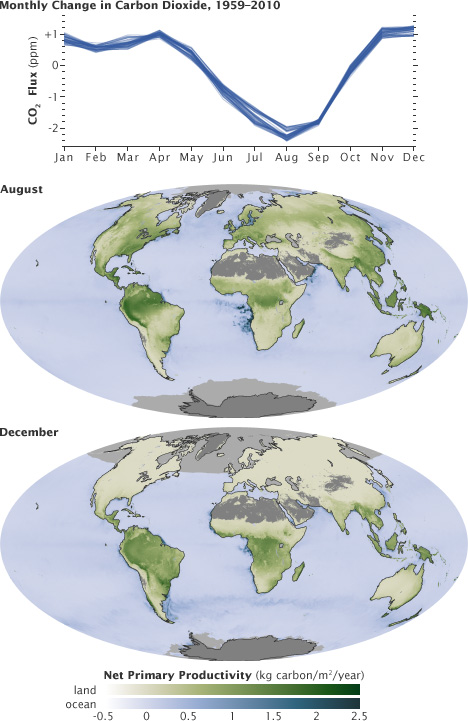

You’ll notice that there is a distinct sawtooth pattern in charts that show how carbon dioxide is changing over time. There are peaks and dips in carbon dioxide caused by seasonal changes in vegetation. Plants, trees, and crops absorb carbon dioxide, so seasons with more vegetation have lower levels of the gas. Carbon dioxide concentrations typically peak in April and May because decomposing leaves in forests in the Northern Hemisphere (particularly Canada and Russia) have been adding carbon dioxide to the air all winter, while new leaves have not yet sprouted and absorbed much of the gas. In the chart and maps below, the ebb and flow of the carbon cycle is visible by comparing the monthly changes in carbon dioxide with the globe’s net primary productivity, a measure of how much carbon dioxide vegetation consume during photosynthesis minus the amount they release during respiration. Notice that carbon dioxide dips in Northern Hemisphere summer.

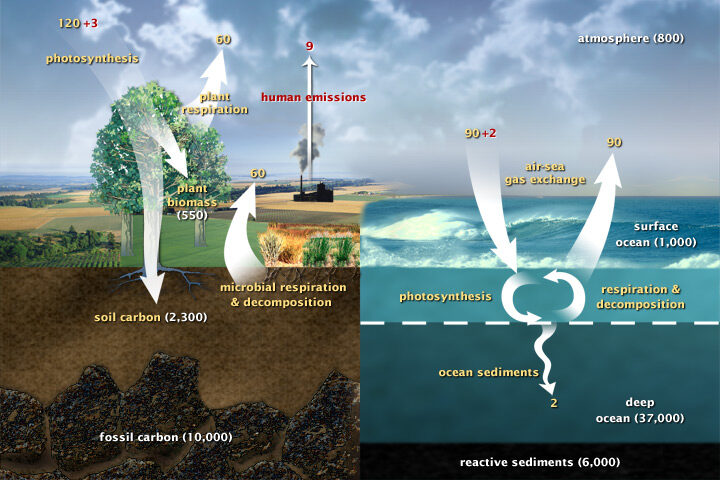

Most of Earth’s carbon—about 65,500 billion metric tons—is stored in rocks. The rest resides in the ocean, atmosphere, plants, soil, and fossil fuels. Carbon flows between each reservoir in the carbon cycle, which has slow and fast components. Any change in the cycle that shifts carbon out of one reservoir puts more carbon into other reservoirs. Any changes that put more carbon gases into the atmosphere result in warmer air temperatures. That’s why burning fossil fuels or wildfires are not the only factors determining what happens with atmospheric carbon dioxide. Things like the activity of phytoplankton, the health of the world’s forests, and the ways we change the landscapes through farming or building can play critical roles as well. Read more about the carbon cycle here.

Image: NASA Earth Observatory/Joshua Stevens. Data courtesy of Hakkarainen, J., Ialongo, I., and Tamminen, J.

A reader recently wrote to ask us about our November 17 article: “Satellite Detects Human Contribution to Atmospheric CO2.”

“Hello, I read on the site that CO2 concentrations are higher in some areas and lower in others. Is the reason for this that the higher zones are near CO2 sources such as heavily populated areas? I always thought gas spread evenly in a container.”

We asked Janne Hakkarainen, a researcher at the Finnish Meteorological Institute and co-author of the study that used OCO-2 data to make satellite-based maps of human emissions of carbon dioxide. Launched in July 2014, NASA’s Orbiting Carbon Observatory-2 (OCO-2) was designed to give scientists comprehensive, global measurements of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere.

Hakkarainen wrote: “Carbon dioxide is indeed well mixed in the atmosphere. This means that if we look at the CO2 concentrations globally, the value is about 400 ppm everywhere.” (That’s 400 parts per million.)

Findings from the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change warn about the consequences of rising CO2 concentrations: “Any CO2 stabilisation target above 450 ppm is associated with a significant probability of triggering a large-scale climatic event.”

“In our recent research paper, we developed a methodology to derive regional CO2 anomalies, which means that we remove from individual CO2 values the regional CO2 median,” wrote Hakkarainen. “When these anomalies are averaged over time, the map highlights the CO2 signal that is not yet mixed and still close to the emission source. The idea is to average out the ‘CO2 weather’ or ‘transport,’ illustrated nicely in this NASA computer simulation (below).”

Another reader asked: “Can someone explain the high CO2 content over the Idaho panhandle and the large area at sea off the Oregon-California border.”

“The Idaho Panhandle anomalies could be related to biogenic sources or fire emissions,” wrote Hakkarainen. For example, NOAA’s CarbonTracker system showed positive fluxes (not including fossil fuel emissions) in that area in 2014.

Image: NASA Earth Observatory/Joshua Stevens. Data courtesy of Hakkarainen, J., Ialongo, I., and Tamminen, J.