In early May 2016, a destructive wildfire burned through Canada’s Fort McMurray in the Northern Alberta region. Windy, dry, and unseasonably hot conditions all set the stage for the fire. Winds gusted over 20 miles (32 kilometers) per hour, fanning the flames in an area where rainfall totals have been well below normal in 2016. Ground-based measurements showed that the temperature soared to 32 degrees Celsius (90 degrees Fahrenheit) on May 3 as the fire spread.

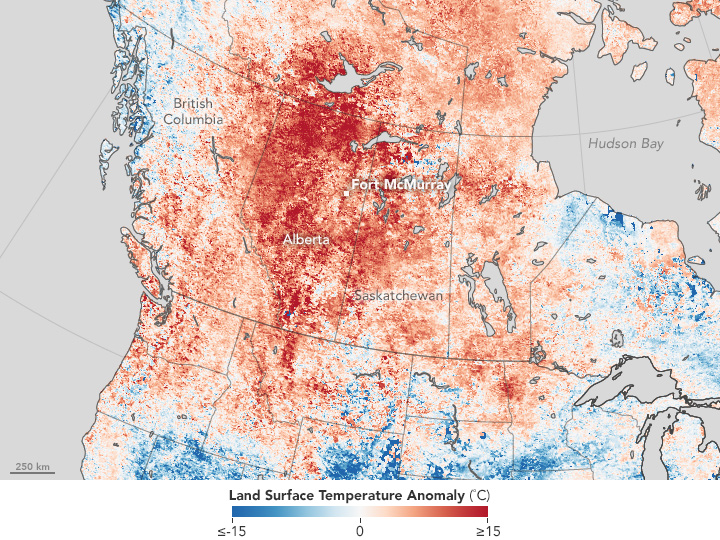

Satellite observations also detected the unusual heat. The map above shows land surface temperature from April 26 to May 3, 2016, compared to the 2001–2010 average for the same one-week period. Red areas were hotter than the long-term average; blue areas were below average. White pixels had normal temperatures, and gray pixels did not have enough data, most likely due to cloud cover.

This temperature anomaly map is based on data from the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) on NASA’s Terra satellite. Observed by satellites uniformly around the world, land surface temperatures (LSTs) are not the same as air temperatures. Instead, they reflect the heating of the land surface by sunlight, and they can sometimes be significantly hotter or cooler than air temperatures. (To learn more about LSTs and air temperatures, read: Where is the Hottest Place on Earth?)

The intense heat coincided with a weather pattern called an omega block. A large area of high pressure stalled the usual progression of storms from west to east. In Alberta, that left sinking, hot air parked over the region while the block was in place. But even before the omega block emerged, seasonal data show that winter in Alberta was warmer than usual.

According to Robert Field, a Columbia University scientist based at NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies, El Niño likely played a role in the warmth. The Virginia Hills fire in central Alberta (May 1998) burned under a similar El Niño phase. “That fire occurred under comparable fire danger conditions, part of which you can trace to El Niño,” Field said.

Fewer people were affected by the Virginia Hills fire, however, because it was located away from a large population center. In contrast, authorities ordered the evacuation more than 80,000 people from Fort McMurray.

The second image above shows Fort McMurray on May 4, 2016, acquired by the Enhanced Thematic Mapper Plus (ETM+) on the Landsat 7 satellite. This false-color image combines shortwave infrared, near infrared, and green light (bands 5-4-2). Near- and short-wave infrared help penetrate clouds and smoke to reveal the hot spots associated with active fires, which appear red. Smoke appears white and burned areas appear brown. On this day the fire spanned about 100 square kilometers (40 square miles); by the morning of May 5, it spanned about 850 square kilometers (330 square miles).“There can be bigger fires, but, in Alberta at least, rarely are they so close to so many people,” Field said. He points out that a fire in Kelowna, British Columbia (2003), and a fire in Slave Lake, Alberta (2011), also affected population centers, “but not this severely.”

Also visible in the Landsat image is the fire’s complex pattern, with many active fronts. “This suggests substantial ‘spotting’, where flaming embers are lofted ahead of a main fire, creating new fires, and making it really hard to fight.”

NASA Earth Observatory image by Jesse Allen using data from the Land Processes Distributed Active Archive Center (LPDAAC). Caption by Kathryn Hansen.