Three thick layers of cake and frosting sat atop Jeff Schmaltz’s kitchen counter. The programmer had completed a 3-D model of a GIBS tile pyramid; it was his entry into a collegial science bake-off at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center. But there was more to this cake than flour and eggs and sugar.

This tile pyramid cake shows a view of the world with Antarctica represented as the largest continent on the map. Credit: Susan Schmaltz.

If you have ever browsed Earth science imagery and data using the online tool Worldview, then you have also used GIBS, Global Imagery Browse Services. GIBS is like a gear behind a clock face, a mechanism that keeps the hands moving. Schmaltz and his colleagues rely on it daily as they assemble images of our dynamic planet. (Worldview is a free and publicly available Earth science browser used by scientists and non-scientists, including the NASA Earth Observatory team.)

How It Works

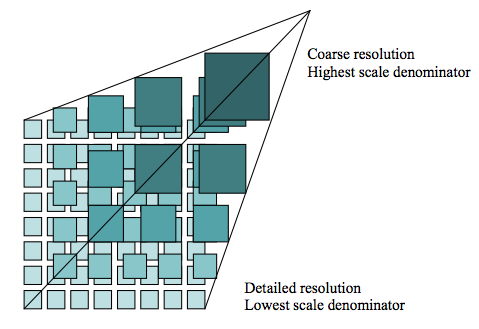

GIBS ingests and organizes satellite data to create a global mosaic. Then, it chops down the data into digestible bits—like that image tile pyramid that Schmaltz recreated with cake—so that users can quickly view Earth as seen from space.

Zoomed out in a broad view, you see just the top tile, the whole Earth in low resolution (like the top layer of the cake). Zoomed in, you see one tile covering a smaller region of the earth but in more detail (like a square from the bottom layer of the cake). On an interface like Worldview, which allows users to scroll and view daily images from the entire surface of Earth, an architecture like GIBS is necessary to keep the site running quickly.

“It’s very fast, and there’s not a lot of computing going on,” Schmaltz said. GIBS does the same thing that Google Maps does: it summons only the data the user requests. By dealing in tiles, the program can serve many people at once without getting bogged down.

GIBS uses tiles (512 x 512 pixels) to speed up data processing. Credit: The Open Geospatial Consortium (OGC).

Way Back When

Not long after NASA launched the Terra satellite in late 1999, the U.S. experienced a record fire season: A record 8.4 million acres burned in the year 2000. At the time, it could take weeks for data from Terra’s MODIS instrument to be processed into images. Scientists hoped that a quicker turnaround might translate into a more informed response to fires. As result, NASA created a near-real time fire pixel product.

Seventeen years later, scientists can visit Worldview to see roughly 150 near-real time data sets from different satellites and sensors as the clouds and snow cover change each day. Air pollution, vegetation cover, dust, smoke are just a few of the data layers users can view.

Credit: NASA.

P.S. To make Jeff’s satellite cake, follow his grandmother’s recipe below:

Ingredients:

Directions:

Mix dry ingredients together. Measure oil, water, egg yolks, and vanilla into a measuring cup and mix; then add to dry ingredients and beat until smooth.

Beat 2 egg whites + ¼ tsp. cream of tartar until stiff. Fold into batter. Slowly mix in grated chocolate.

Bake in ungreased 8×8 pan at 350 degrees for 20-25 minutes. Check with toothpick when done. Cool on a rack. Goes best with chocolate frosting. (Schmaltz uses the recipe on the side of a Hershey’s can.) Alternately, you can top the cake with an edible print of a satellite image.

Credit: Adam Voiland.

The following is an excerpt from a story by Maria-Jose Vinas, NASA’s Earth Science News Team

Defying 30 mph gusts and temperatures down to minus 22°F, NASA’s new polar rover, GROVER, recently demonstrated in Greenland that it could operate completely autonomously in one of Earth’s harshest environments. The solar-powered robot, developed by students, was able to execute commands sent from afar over an Iridium satellite connection and collect radar data that will allow scientists to study snow and ice accumulation in Greenland.

To learn more about GROVER, check out this web feature.