Thirteen years ago, a satellite acquired this beautiful image (above) of light and sand playing off a portion of the ocean floor in the Bahamas. The caption that accompanied the image didn’t include many details, only noting that the image was acquired by the Enhanced Thematic Mapper Plus (ETM+) sensor on Landsat 7 and that, “tides and ocean currents in the Bahamas sculpted the sand and seaweed beds into these multicolored, fluted patterns in much the same way that winds sculpted the vast sand dunes in the Sahara Desert.”

An image as beautiful as this seemed like it deserved a bit more explanation, so I grabbed a recent (January 9, 2014) scene of the same area captured by the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) on the Aqua satellite. That image (below) shows a much broader view of the area. You can still see some details of the intricate network of dunes, but the MODIS image offers a much better sense of the regional geology. For instance, the section of dunes shown in the first image (the white box in the lower image) appear to be shoals made up small spherical grains of calcium carbonate known as ooids that sit on a larger limestone platform called the Great Bahama Bank. Limestone is a sedimentary rock formed by the skeletal fragments of sea creatures, including corals and foraminifera, and this particular limestone platform has been accumulating since at least the Cretaceous Period.

You can also see a sharp division between the shallow (turquoise) waters of the Great Bahama Bank and the much deeper (dark blue) parts of the ocean. The submarine canyon that separates Andros Island from Great Exuma Island is nearly cut off entirely from the ocean by the Great Bahama Bank, but not quite. A connection to deep waters to the north gives the trench the shape of a tongue, earning the feature the name “Tongue of the Ocean.” At its lowest point, the floor of the Tongue of the Ocean is about 14,060 feet (4,285 meters) lower than Great Bahama Bank. The shallowest (lightest) parts of the the feature, in contrast, are just a few feet deep.

Last week, a city-state sized chunk of ice broke off of Pine Island Glacier (PIG), sending iceberg B-31 into a bay off West Antarctica. Though the formation of the 700 square-kilometer iceberg could be a purely natural event — the result of a floating ice tongue growing too long and losing its balance on the sea — some scientists suspect that changes in Pine Island Glacier are due to changing conditions below.

Five years ago this week, another block of ice broke off of the Antarctic Peninsula (radar image above from November 26, 2008). The seaward edge of Wilkins Ice Shelf spent much of 2008 breaking loose from the continent. Unlike PIG, Wilkins shattered and splintered into much smaller bits. And in that case, few doubted that global warming — or at least warming of the Antarctic Peninsula — played a major role.

NASA satellites are still tracking the last week’s PIG offspring. Check out these images from:

Hindus are celebrating Diwali this week. That means cities and towns around the world—but particularly in South Asia—are ablaze with lamps, candles, and firecrackers. It’s also become a tradition (of sorts) to share a colorful image via social media that was supposedly taken by a satellite during Diwali. If that image turns up on your feed, be skeptical.

As we pointed out last year, that image is a composite created and colored back in 2003 by NOAA scientists to illustrate population growth over time. In reality, India during Diwali looks something more like the image you see at the bottom of this page. The fact is that any extra light produced during Diwali would be so subtle that it would be extremely difficult to detect from space.

The Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite (VIIRS) on the Suomi NPP satellite collected the data that was used to make the image below on November 12, 2012. Read more about the fake Diwali image from Earthsky or USA Today.

One year ago today, citizens of New Jersey, New York, Connecticut, and much of the northeastern United States woke up to flooded avenues and homes, wind-ravaged neighborhoods, blackouts, and ripped up trees, coastlines, and lives. In the dark, early hours of October 30, 2012, the VIIRS instrument on the Suomi NPP satellite caught this glimpse of the monster storm named Sandy, a hurricane that collided with two other weather fronts and merged into one of the most destructive storms in recorded American history.

Our gallery of Sandy images conveys an abstract, distant sense of the event. In satellite images, the eye is drawn to the awesome and beautiful cloud forms; to the potent, organized march across the skies; to the incredible scale of the storm. But the shoreline of my New Jersey childhood was nearly wiped clean, and a satellite can’t really show that. It’s not until you get down to the street level — such as the aerial photo below — that the human cost comes into better focus.

The odds said Sandy shouldn’t happen; it was too late in the season, and too far north for a hurricane. But the odds of such storms seem to be changing as the world grows warmer and the weather grows a bit less predictable. Read our feature story on how storms may become less frequent but more destructive.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change has some good insights on anticipating and preparing for a future where extreme storms like Sandy could become more likely and more devastating. It should be required reading if you live near the coast.

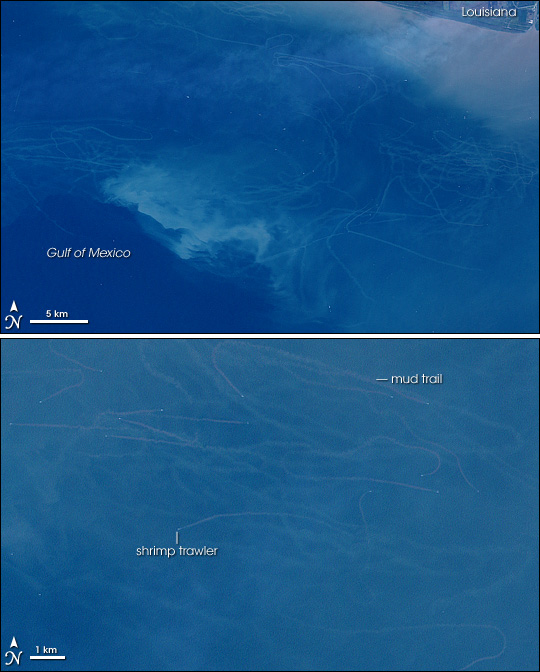

Fourteen years ago, the Enhanced Thematic Mapper Plus on Landsat 7 acquired these images of mud trails off the coast of Louisiana. They were caused by bottom trawling in the Gulf of Mexico, a fishing technique that involves dragging large nets across the sea floor.

Bottom trawling is an efficient way to scoop up shrimp and squid, but that’s not all that ends up in the nets. As our earlier caption explained: “In addition to harvesting intended species, many trawls indiscriminately capture non-target species, like sea turtles, which are discarded. Trawling crushes or destroys the seafloor habitat that feeds and shelters marine life; the nets literally scrape the mud off the ocean bottom. As the mud resettles, it can smother surviving bottom-dwelling creatures.”

Some things have changed and some things have stayed the same since this image was acquired in 1999. In 2006, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration prohibited bottom trawling off of most of the Pacific Coast of the United States. Other countries—including Norway, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand—have also taken steps to discourage the practice. Yet in many parts of the world, including the U.S. Gulf Coast, the practice persists. You can read more about bottom trawling in the Gulf of Mexico from Sky Truth, the Gulf of Mexico Fishery Management Council, and Science Daily.

Bottom trawling isn’t the only type of fishing visible from space. Read our new feature about the city of light that appears off the coast of southern Argentina.

[youtube lbSQhy0axH0]