In the summer of 2012, Arctic sea ice has broken the previous record for minimum extent (set in 2007), fallen below 4 million square kilometers, and, as of September 17, dropped below 3.5 million square kilometers in extent. Multiple studies indicate that the Arctic will eventually lose its sea ice during the summers of the future.

As summer sea ice shrinks, the ice edge—the perimeter of the ice pack that remains—will retreat farther north. Meanwhile, the satellites that observe the ice can see almost as far north as the North Pole—but not quite. As a result, scientists and data managers at institutions such as the National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC) are looking for ways to cope with a situation that was once unexpected.

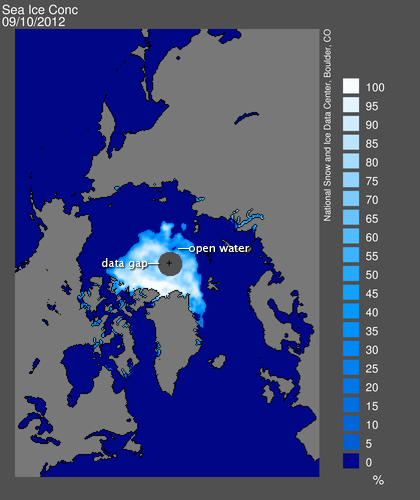

Since 1979, scientists have relied on a variety of satellite sensors, including the Scanning Multichannel Microwave Radiometer (SMMR), the Special Sensor Microwave/Imager (SSM/I), the Advanced Microwave Scanning Radiometer – Earth Observing System (AMSR-E), and (most recently) the Special Sensor Microwave Imager/Sounder (SSMIS). The satellites carrying these sensors fly in near-polar orbits (see the Catalog of Earth Satellite Orbits for more information). This means that they pass close to the pole, but not quite over it. As a result, many sea ice images have a gap in the data extending from 87 degrees northward to the North Pole. The gap appears as a black circle over the pole in the image from August 2012.

Over the years, sensor capabilities have improved, shrinking the data gap over the North Pole. “For instance, SSM/I only saw as far north as 87 degrees, but AMSR-E and SSMIS can see up to 89 degrees north,” explains NSIDC’s Walt Meier. But to be consistent with satellite data from earlier years, NSIDC often stuck with the larger data gaps, treating the whole area the same way from year to year. This worked well for years because the entire region could be safely assumed to be ice-covered. “There might have been some small areas of open water, but nothing significant.”

The reliable presence of sea ice above 87 degrees north has long simplified how NSIDC measures sea ice. The smallest “unit” that a satellite sensor sees is known as a pixel, and the sensors measuring sea ice can have pixels as big as 25 by 25 kilometers. Sea ice concentration is the percentage of any pixel covered by ice. NSIDC uses a threshold of 15 percent and considers any pixel that is more than 15 percent ice covered completely ice filled. The resulting measurement is known as sea ice extent.

Historically, NSIDC scientists have handled the data gap over the North Pole by assuming it was ice-filled, and adding that area to the extent observed outside the data gap. But the continued retreat of sea ice presents a potential problem, especially if scientists stick with the historic data gap from 87 degrees northward to the pole. First-year, melt-prone ice is spreading northward. “In the past, we didn’t see first-year ice that far north,” Meier says. In addition, the 2012 melt season produced a surprising area of open water. “The open water is getting close to the 87-degree data gap.”

The data gap doesn’t pose an immediate problem for NSIDC’s sea ice estimates, but Meier acknowledges that changes may be advisable in the long run. “If the ice retreats past the current data gap, going to a smaller one may be beneficial. We won’t be able to just assume it’s filled with ice.”

This northward migration of the ice edge is another reminder—in an already historic summer—of how fast the Arctic is changing.