The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change stated in their most recent report that global surface temperature at the end of this century will probably be between 1.8 and 4 degrees Celsius warmer than it was at the end of the last century.

It’s natural to question whether we and future generations will regret our efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions if it turns out global warming isn’t as bad as predicted. But the best science we have to guide us at this time indicates that the chance that warming will be much larger than the best estimate is greater than the chance that it will be much smaller.

Climate scientists know that there is plenty they don’t know about the way the Earth system works. Some of the physical processes that models describe are thoroughly well-established—the melting point of ice, for example, and the law of gravity.

Other physical processes are less perfectly known: when the air temperature is not far below 0 Celsius, for example, will water vapor condense into liquid or ice? Either is possible, depending on atmospheric conditions.

To understand how uncertainty about the underlying physics of the climate system affects climate predictions, scientists have a common test: they have a model predict what the average surface temperature would be if carbon dioxide concentrations were to double pre-industrial levels.

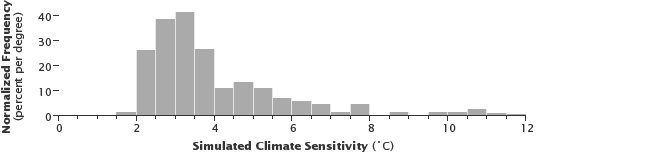

They run this simulation thousands of times, each time changing the starting assumptions of one or more processes. When they put all the predictions from these thousands of simulations onto a single graph, what they get is a picture of the most likely outcomes and the least likely outcomes.

The pattern that emerges from these types of tests is interesting. Few of the simulations result in less than 2 degrees of warming—near the low end of the IPCC estimates—but some result in significantly more than the 4 degrees at the high end of the IPCC estimates.

This pattern (statisticians call it a “right-skewed distribution”) suggests that if carbon dioxide concentrations double, the probability of very large increases in temperature is greater than the probability of very small increases.

Our ability to predict the future climate is far from certain, but this type of research suggests that the question of whether global warming will turn out to be less severe than scientists think may be less relevant than whether it may be far worse.

-

References:

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Core Writing Team. (2007). Chapter 3: Climate change and its impacts in the near and long term under different scenarios. In Pachauri, R. & Reisinger, A. (Eds.), Climate Change 2007: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Geneva, Switzerland: IPCC.

- Ramanathan, V., & Xu, Y. (2010). The Copenhagen Accord for limiting global warming: Criteria, constraints, and available avenues. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 107(18), 8055.

- Realclimate.org. (2007, October 26). The certainty of uncertainty. Accessed June 21, 2010.

- Roe, G. H., & Baker, M. B. (2007). Why Is Climate Sensitivity So Unpredictable? Science, 318(5850), 629-632.

- Stainforth, D. A., Aina, T., Christensen, C., Collins, M., Faull, N., Frame, D. J., Kettleborough, J. A., et al. (2005). Uncertainty in predictions of the climate response to rising levels of greenhouse gases.