|

|||

by Michon Scott · design by Robert Simmon and Michon Scott · February 9, 2007 Hydrologist Bernhard Lehner is from Bavaria—the birthplace, he quips, of beer. College dreams of starting a brewery with friends prompted his choice to study water. While his friends wound up in the brewing business, Lehner stuck with science. After graduation, he went to work as a hydrologist with the conservation group World Wildlife Fund. There, he encountered a paradoxical problem: often, the places he most wanted to study had the poorest maps. In remote parts of the world, detailed maps are rare at best. Yet, precisely because they haven’t been extensively populated and paved, remote regions contain some of the most intact biodiversity on Earth. With development looming in even Earth’s most remote regions, conservation biologists want to recommend the best places to protect, but without thoroughly knowing an area, they struggle to give governments and policymakers good advice. Lehner’s efforts to solve this problem for a remote corner of the Amazon eventually became a stepping stone for a much more ambitious project: a detailed, digital map of water channels for the entire globe. |

Image in title graphic courtesy Photos.com. |

||

|

|||

Amazon Stepping StoneIn 2004, Lehner, Robin Abell (his manager at World Wildlife Fund), and their colleagues faced a predicament as they examined the Madre de Dios River in Peru and Bolivia, in the southwest Amazon Basin. Abell, a freshwater conservation biologist, was trying to characterize the habitats in the region to figure out what sort of networks of protected and managed areas would best represent the area’s wide variety of freshwater ecosystems. |

Remote tropical forests, including the Amazon, are home to much of the Earth's remaining intact biodiversity. Some examples of the Amazon’s diverse wildlife include numerous species of (left to right) butterflies (© 2005 Tina Carlson), frogs (© 2006 Steve Makin), primates (© 2006 radiospike), trees (© 2006 Shannon Roy), and fish (© 2006 Big-E-Mr-G). |

||

|

|||

The area was far too big for personal inspection, and existing maps weren’t much help. Detailed maps of the Amazon Basin varied by country, with differing scales and map projections. But wildlife doesn’t care about national borders, and Abell and her collaborators needed a consistent map format. “The best product we had was a USGS [United States Geological Survey] product of 1-kilometer spatial resolution,” Lehner explains. “There was nothing wrong with it, but to derive high-quality river maps, it was just not good enough.” |

Abell, Lehner, and their colleagues initially studied watersheds around the Madre de Dios River in South America. (© 2005 damclean.) |

||

|

|||

Lehner and Abell needed a more detailed data source, and for that Lehner turned to topographic maps based on radar data from an 11-day mission flown by NASA’s Space Shuttle Endeavour in February 2000. Called the Shuttle Radar Topography Mission, or SRTM, for short, the mission produced the most complete high-resolution, digital topographic map of the Earth. The map was a hundred times more detailed than the satellite data Lehner had considered using before. |

The Madre de Dios region lies just east of the Andes Mountains in Peru and Bolivia. Attempts to map freshwater habitats in the Madre de Dios watershed laid the foundation for efforts to create a global, digital hydrologic map. (Image by Jesse Allen, NASA Earth Observatory, using data from Natural Earth.) |

||

|

|||

Lehner used SRTM data as the foundation for a digital map of the headwaters of the Madre de Dios, letting the topographic data reveal where rivers would be if he traced the path of water flowing downhill. After combining the digital river map with information on land surface characteristics like geology and vegetation, Lehner, Abell, and their collaborators were able to recommend protecting two continuous corridors from the mouth of the Madre de Dios to its headwaters in the Andes. Perhaps more significantly, the project showed how valuable space-based topography data could be for understanding remote, poorly mapped regions. The case study of the Madre de Dios quickly drew admiration from other conservation scientists. “After people saw it,” Lehner recalls, “they kind of pushed me to map rivers and watersheds for the entire Amazon, and even all of South America.” Pressed to expand his work, however, Lehner gave a surprising answer. He said no. |

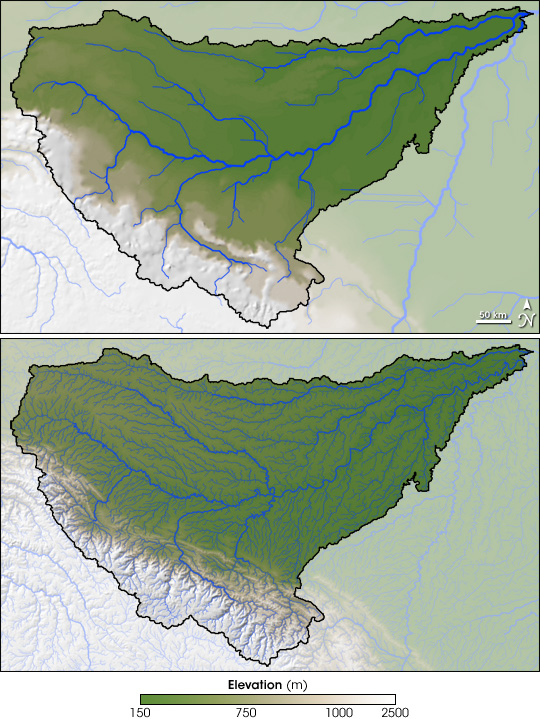

Previously available hydrological maps of the Madre de Dios watershed (top) were not detailed enough for freshwater-habitat conservation planning in a place as biologically diverse as the Amazon. The Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM, bottom) provided roughly 100 times the level of detail, allowing scienitsts to map many more rivers and streams (blue lines). (NASA images by Jesse Allen, based on SRTM and Hydro1K data from the U.S. Geological Survey.) |

||