Sap-sucking insects called hemlock woolly adelgids are draining the life from a common evergreen tree in the eastern United States. Since arriving from Japan in the 1950s, the tiny bugs have spread from Georgia to Maine—about half of the Eastern hemlock’s range. Once the bugs become well-established, the consequences can be grave. Areas with severe infestations can see up to 90 percent of hemlocks die within about ten years.

The prognosis for infested hemlocks in the southern part of their range is particularly grim because cold winters help control the pests, and cold winters are becoming less common. The hemlock wooly adelgids have hit the southern Appalachian Mountains of North Carolina and Tennessee hard—areas where hemlocks once thrived in river and stream valleys. During the past decade, the bugs have turned high percentages of hemlocks there into eerie, skeleton-like snags—dead or dying leafless trees that are still standing. The photograph above shows several of these “gray ghost” trees along the lower slopes of the Linville Gorge in North Carolina.

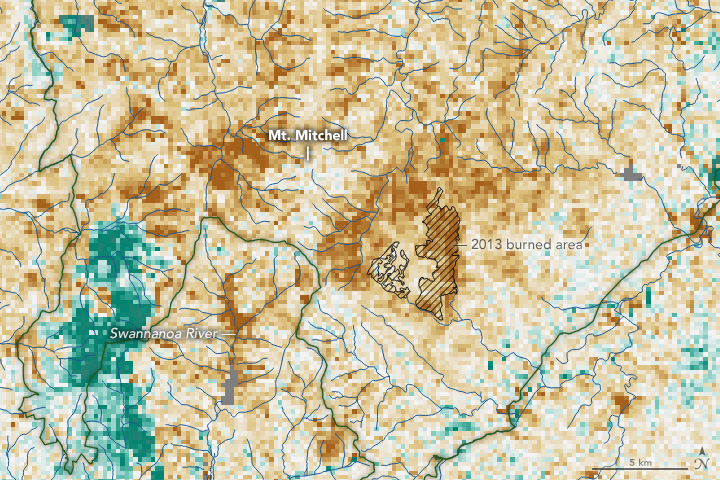

The map at the top of the page, based on satellite data collected by the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) on NASA’s Terra and Aqua satellites, shows where hemlock decline has occurred near North Carolina’s Mount Mitchell, the highest point in the Appalachians. The map depicts Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI), a measure of the health and greenness of vegetation based on how much red and near-infrared light plant leaves reflect. Healthy vegetation with lots of chlorophyll reflects more infrared light and less visible light than stressed vegetation.

The map shows vegetation health in February 2016. Brown indicate forests that were less healthy—had less green vegetation—during that month than usual for that time of year. Most of the areas of decline had severe hemlock woolly adelgid infestations, explained Steve Norman, an ecologist with the U.S. Forest Service. Since hemlocks tend to grow in stream valleys in high-elevation areas and along the north-facing slopes of mountains, the most tree damage is clustered in these places. For instance, the bugs have damaged large numbers of hemlocks along the Swannanoa River and on the north slope of Mount Mitchell. A prescribed fire in 2013 also caused a sharp change in NDVI to the southeast of Mount Mitchell; this area is shown in gray.

Norman and colleagues have been monitoring the destructive impact of the adelgids with ForWarn, an NDVI tracking and data analysis tool developed by the U.S. Forest Service with assistance from NASA’s Applied Sciences program. ForWarn generates near-real time maps of vegetation changes in the continental United States. “What surprised many of us was the rate at which this happened,” said Norman. “Though the insects arrived in the Southern Appalachians decades later than they did in the Northeast, large numbers of hemlocks have died off in the Southeast much more quickly.”

NASA Earth Observatory images by Jesse Allen, using MODIS-derived data provided by William Christie (US Forest Service) and ASTER GDEM2 data from NASA/GSFC/METI/ERSDAC/JAROS, and U.S./Japan ASTER Science Team. Photo by Steve Norman (U.S. Forest Service). Caption by Adam Voiland.