Fires in Indonesia are not like most other fires. They are extremely difficult to extinguish. They smolder under the surface for long periods, often for months. Usually, firefighters can only put them out with the help of downpours during the rainy season. And they release far more smoke and air pollution than most other types of fires.

The root cause is large deposits of peat—a soil-like mixture of partly decayed plant material formed in wetlands—lining the coasts of Borneo and Sumatra. Peat fires start to burn in Indonesia every year because farmers engage in “slash and burn agriculture,” a technique that involves frequent burning of rainforest to clear the way for crops or grazing animals. In Indonesia, the intent is often to make room for new plantings of oil palm and acacia pulp.

“Most burning starts on idle, already-cleared peatlands and escapes underground into an endless source of fuel,” explained David Gaveau of the Center for International Forestry Research.

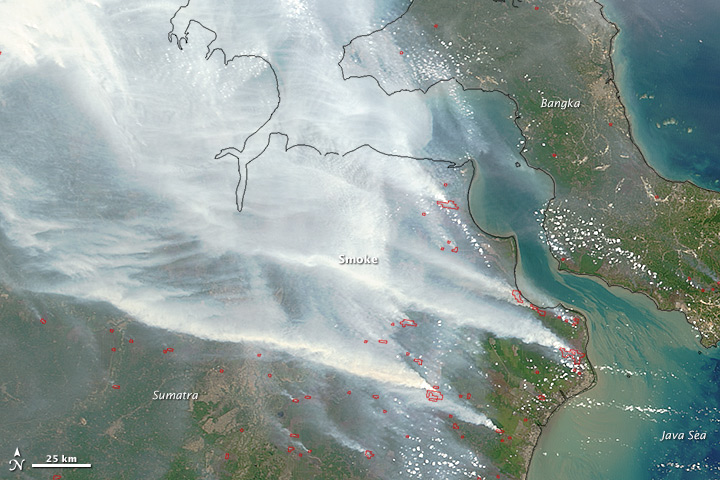

As seen in this September 24 image from the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) on NASA’s Terra satellite, 2015 is no exception. Red outlines indicate hot spots where the sensor detected unusually warm surface temperatures associated with fires. Thick gray smoke hovers over both islands and has triggered air quality alerts and health warnings in Indonesia and neighboring countries. Visibility has plummeted.

Scientists monitoring the fires are concerned that the problem will get worse before it gets better. That’s because strong El Niños, like the one currently brewing in the Pacific, lengthen the dry season and reduce the amount of rainfall. During a strong El Niño in 1997, the lack of rain allowed fires to burn out of control on a wide scale, releasing record levels of air pollution and greenhouse gases.

“We are on a similar trajectory to other bad years,” said Robert Field, a Columbia University scientist based at NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies. “Conditions in Singapore and southeastern Sumatra are tracking close to 1997, with some stations having visibility less than 1 kilometer (0.6 miles) on average for a week. In Kalimantan, there have been reports of visibility less than 50 meters (165 feet).”

Aerosol optical depth data (collected by MODIS) show particle levels similar to the peak in 2006, the last major burning event. This time, however, the high levels are occurring several weeks earlier. “If the forecasts for a longer dry season hold,” said Field, “this suggests 2015 will rank among the most severe events on record,”

Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam scientist Guido van der Werf has been monitoring the number and size of the Indonesian fires with MODIS. “There are more and larger fires this year. We are on a track above any other year since 2001, when MODIS observations became available,” he said. “And we are only halfway through the fire season.”

Along with colleagues at NASA and the University of California, Irvine, van der Werf has developed a technique to estimate the amount of trace gases and airborne particles that fires emit—many of them pollutants—based on satellite observations of fires and vegetation cover. The project, known as the Global Fire Emissions Database (GFED), produces both regional and global estimates of fire emissions based on data from 1997 to the present. According to the GFED analysis, the 2015 Indonesia fires have released greenhouse gases equivalent to about 600 million tons through September 22, a number that rivals carbon dioxide a year of carbon emissions from Germany.

NASA image by Adam Voiland (NASA Earth Observatory) and Jeff Schmaltz (LANCE MODIS Rapid Response). Caption by Adam Voiland.