In late March 2015, flash floods and mudslides devastated northern Chile’s Antofagasta, Atacama, and Coquimbo regions. By the standards of most of the world, the rainfall totals were not extraordinary. But in a desert region that sees miniscule amounts of rainfall in any year, the heavy rains were disastrous.

According to news accounts and several meteorologists, it was the heaviest and most extensive rainfall in the Atacama Desert region in nearly a century. Rain totals barely exceeded 50 millimeters (2 inches), but they came in one of the driest regions of the world. The town of Antofagasta received 24 millimeters (an inch) of rain on March 25-26; with a yearly average of 1.7 millimeters, that was about 14 years worth of rain in a day. The town of Quillagua saw its first rain in 23 years.

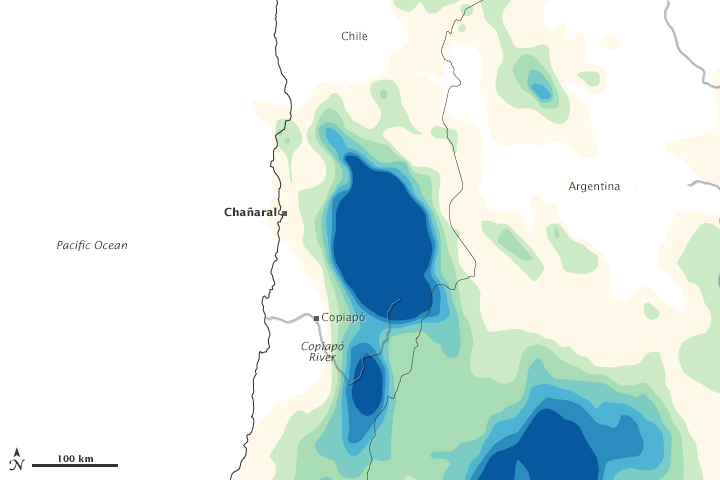

Parched soil and sediment turned to thick mud that flowed in a torrent. At least 26 people were killed by the floods, and 120 were still missing two weeks afterward. At least 2,000 homes were swept away, and 6,000 more were severely damaged by thick mud, boulders, and debris. The most extensive damage appeared to be in the towns of Chañaral and Copiapó.

The rare rainfall in northern Chile was caused by a cold front that moved across the Andes. Normally such a storm would have brought snow to the mountains, but air and sea surface temperatures in the region have been several degrees above normal—turning the snow into rain. Some meteorologists suggested that this fits with El Niño weather patterns.

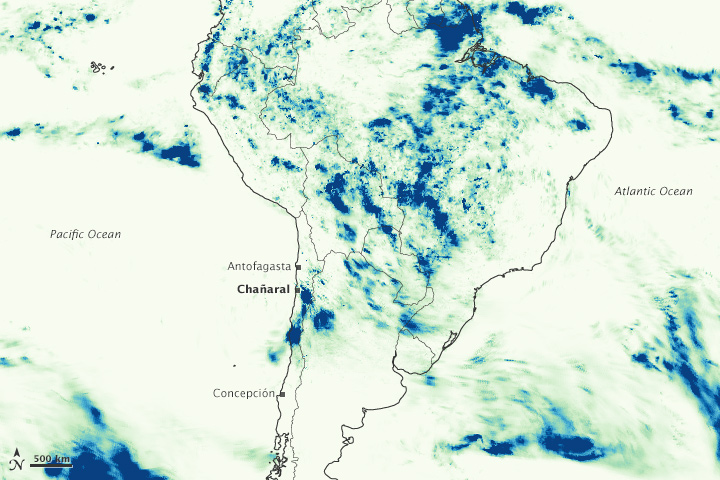

The maps above show satellite-based estimates of rainfall totals and locations from March 25–27, 2015, as compiled by NASA. On the top map, note how the rainfall in northern Chile is almost average compared to the events north and east in the Amazon basin. The rainfall totals are regional, remotely-sensed estimates, and localized rainfall amounts can be significantly higher when measured from the ground.

The data come from the Integrated Multi-Satellite Retrievals for GPM (IMERG), a product of the new Global Precipitation Measurement mission that merges precipitation estimates from passive microwave and infrared sensors, as well as monthly surface precipitation gauge data to provide precipitation estimates between 60 degrees North and South latitude. The GPM satellite is the core of the rainfall observatory that includes measurements from 12 satellites from NASA, the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency, and five other national and international partners.

NASA Earth Observatory image by Jesse Allen, using IMERG data provided courtesy of the Global Precipitation Mission (GPM) Science Team’s Precipitation Processing System (PPS). Caption by Mike Carlowicz.