In April 2016, the waters of Lake Kivu in central Africa changed color unexpectedly. The blue freshwater lake turned milky in color, as viewed from boats and from space. Such a sudden change would attract the attention of people anywhere in the world, but it commands particular attention when you live on the edge of a lake known to harbor potentially deadly stores of gas.

Lake Kivu is one of Africa’s “great lakes,” and it straddles the border between Rwanda and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. The lake is a source of drinking water and fish, as well as a transportation route, ;for nearly two million people.

But it is also connected to the volcanic plumbing of the East African Rift. There are vast stores of dissolved methane and carbon dioxide in the depths of Lake Kivu, which is a concern because other lakes in Africa have been known to abruptly discharge gas and suffocate people nearby. For this reason, scientists have been monitoring water and volcanic conditions through the Lake Kivu Monitoring Program (LKMP), and engineers have been developing a platform for extracting those gases to produce energy and to reduce the hazard.

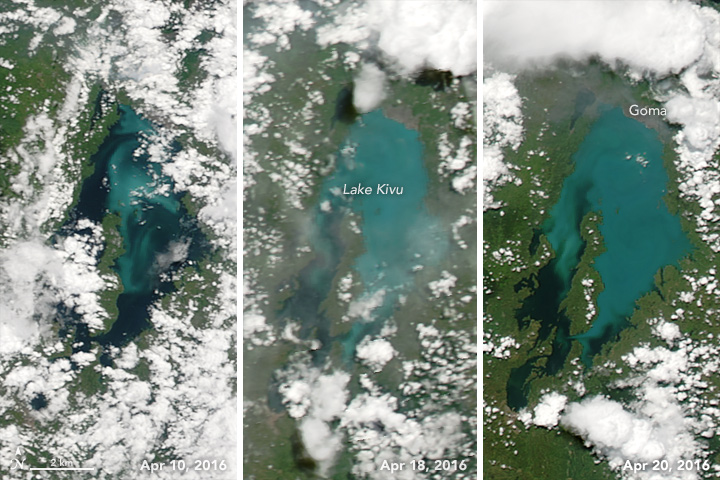

Augusta Umutoni, head of the LKMP, noted that another research team detected some seismic and volcanic activity in the region in April, which initially heightened concern about the lake. But observations by Umutoni’s team showed that this month’s color change was actually much less ominous. Lake Kivu is going through a “whiting event” similar to those that occasionally happen on the Great Lakes of North America and several large lake (such as Geneva) in Europe. The Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) instruments on NASA’s Terra and Aqua satellites peeked through the clouds to acquire three natural-color images of the lake whiting event on April 10, 18, and 20, 2016.

Whiting occurs when air and water temperatures rise, as does the pH level near the surface, in a lake that is rich in calcium carbonate. As the temperature and pH rise, the carbonates start to precipitate out of the water as calcite particles that have a white or gray color. Phytoplankton blooms can also lead to whiting-like effects.

“We don’t yet know for sure what caused this particular whiting event at Lake Kivu,” said Martin Schmid of the Swiss Federal Institute of Aquatic Science and Technology. “It is certainly unusually strong, but there have been similar weaker events before. It can be caused by a phytoplankton bloom, by high surface water temperatures, or by a combination of both.”

Robert Hecky of the University of Minnesota-Duluth added that mixing of the surface waters with lower layers can bring up more calcium and nutrients from the depths, promoting blooms or whiting events. “The mixing is an annual event, but the intensity of response of carbonate precipitation varies,” he said. “East African lakes do respond to El Niño events, and the current El Niño may also have had an affect on the physical processes in the lake.”

NASA images by Jeff Schmaltz, LANCE/EOSDIS Rapid Response. Caption by Michael Carlowicz, with image interpretation help from Cynthia Ebinger (University of Rochester), Jarmo Gummerus (ContourGlobal/KivuWatt Ltd.), and Augusta Umutoni (Lake Kivu Monitoring Program).