Winter storms can blanket Iceland almost entirely with snow. The relative warmth of summer and fall, however, exposes a spectacular, varied landscape. The Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) on NASA’s Terra satellite acquired this natural-color view of the Nordic island nation on November 9, 2015.

“The visible snow cover is typical for this time of the year, compared to conditions during the past 15-20 years,” said Thorsteinn Thorsteinsson, a glaciologist at the Icelandic Meteorologial Office. He noted, however, that compared to the reference period of 1961-1990, snow cover is “almost certainly” less than average in the highland and mountain regions above 400 meters in elevation.

The melting of seasonal snow cover accentuates the boundaries of Iceland’s permanent ice caps. The ice caps appear smooth and rounded in contrast with the snow-covered interior plateau or the snow-capped ridges along the glacier-carved coastline.

All ice caps in Iceland have been retreating rapidly and losing volume since 1995. In October 2015, however, scientists from the Icelandic Met Office showed that the Hofsjökull ice cap, outlined in red, had gained mass according to their ground-based measurements.

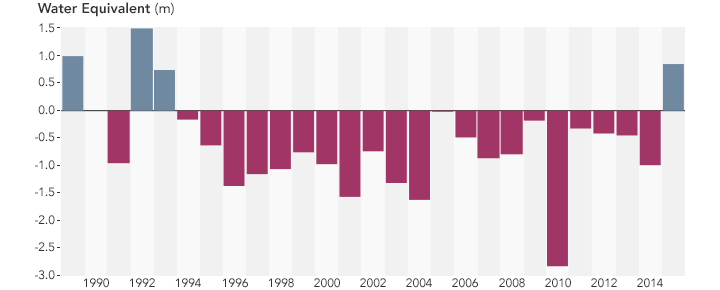

An ice cap that has gained more mass than it has lost is said to have a positive mass balance. The graph below the image shows the annual mass balance of Thjórsárjökull, one of the ice cap’s three basins, since the start of measurements in 1989. Thjórsárjökull’s mass balance in 2015 was positive for the first time since 1993.

The ice cap’s reversal in 2015 is due to abundant winter precipitation and cool summer temperatures, explained Thorsteinsson. In spring 2015, the thickness of winter snowfall on the ice cap’s three basins ranged from 25 to 60 percent above the 1995-2014 average. In the summer, melting was limited because of cool northerly winds.

The situation changed in the fall, as September and October were unusually warm. When temperatures rise, melt water flows into the island’s numerous lakes and reservoirs. Hálslón reservoir, the long and narrow feature on the east side, holds glacial meltwater. Öskjuvatn crater lake, Hágöngulón reservoir, and Thórisvatn natural lake and reservoir also stand out because they are dark and surrounded by snow.

But one of the more prominent dark features just south of Öskjuvatn, is not water at all. “At first sight, one might think that this is another highland lake,” Thorsteinsson said. “But actually, it is a fresh lava field” from the Holuhraun eruption from August 2014 to February 2015. During the eruption, lava poured from fissures just north of the Vatnajökull ice cap and near the Bárðarbunga volcano. By January 2015, the Holuhraun lava field had spread across more than 84 square kilometers (32 square miles). False-color satellite imagery here and here make it even more apparent that Holuhraun is not a lake.

NASA Earth Observatory images by Joshua Stevens and Jeff Schmaltz, using mass balance data courtesy of Thorsteinn Thorsteinsson, Icelandic Met Office and MODIS data from LANCE/EOSDIS Rapid Response. Caption by Kathryn Hansen.