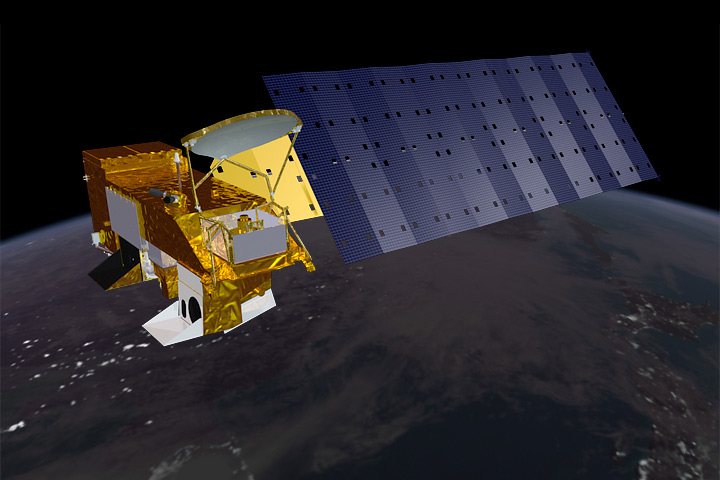

Sent into orbit to monitor Earth’s atmosphere and water systems, NASA’s Aqua satellite must maintain a very precise orbit. Gravity pulls at the satellite, gradually tugging it towards the equator and making it necessary for engineers in mission control to correct the orbit. This article follows events during a recent orbital adjustment maneuver.

April 23, 2009, 15:12:00 UTC: NASA’s Aqua satellite comes around the limb of the Earth into the view of an orbiting Tracking and Data Relay Satellite in position to connect Aqua with its controllers on the ground. The Earth beneath Aqua is dark, except perhaps for moonlight reflecting off clouds over the icy North Pacific Ocean.

In Aqua’s Mission Control Center at NASA Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, it is 11:12 in the morning on a sunny, cool spring day. A group of engineers have gathered in two adjoining control rooms. Each sits at a computer station tracking the satellite’s position and status in dark-colored charts and lines of computer code. Above them, blue neon numbers flash a countdown: 40 minutes until loss of signal. In 40 minutes, the satellite moves out of view of either the data relay satellite or a ground station. In that time, they have to turn the satellite approximately 90 degrees, fire the thrusters to alter its orbit, and then turn the satellite to face forward again, ready to collect data. They’ve been planning this move for more than a year.

15:15:14 UTC: Aqua’s onboard computer detects that the satellite is pointing the wrong direction. It should correct this error by turning 86.466 degrees to the right. It fires its four thrusters to initiate the turn.

The error is a fiction, sent to the computer earlier to get the satellite to turn itself around, or “slew out” in engineer speak. In Mission Control, guidance, navigation, and control engineers Scott Blanchard and John Nidhiry watch the data flowing down from the satellite, tracking to see if the satellite will follow the commands they had previously sent to it. Blanchard lifts a blocky phone (the “SCAMA,” or station conferencing and monitoring arrangement):”Initiating slew out.” His voice carries over the SCAMA to identical devices at each station in the room or anywhere else in the world where team members might be gathered. A few feet away, flight systems manager James Pawloski responds into the intercom system: “Copy, flight.” 36 minutes and 46 seconds are left.

If things go according to plan, the turn should take 9 minutes and 55 seconds. The turn is necessary because the flight team plans to shift Aqua’s orbit closer to the pole by a hundredth of a degree to maintain the strict orbit required for precise science measurements of Earth’s oceans and water cycle.

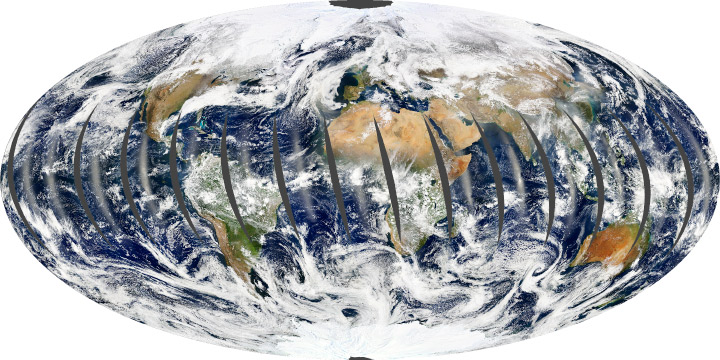

On the daytime side of the Earth, Aqua orbits from south to north (called an ascending polar orbit), not passing directly over either pole, but coming close to each. Crossing near the North Pole onto the nighttime side of Earth, the satellite moves south again to the South Pole. As the satellite circles, the Earth spins underneath it, so that on each orbit, Aqua is over a different place on Earth. In a single day, the widest-viewing sensor on the satellite will cover most of the Earth’s surface.

Aqua is a scientific research satellite, sent into orbit to provide information about Earth’s water systems—both in the atmosphere and on the surface. Such measurements are crucial to understanding the climate system. If they are to be used to study climate change, the measurements must be consistent over time so that scientists can make valid comparisons. That means that each measurement needs to be taken at about the same time of day to ensure that the angle of the sunlight falling on the ocean, atmosphere, or land and reflecting back to the satellite is as consistent as possible.

To achieve this consistency, Aqua is in a polar orbit that takes it over the equator between 1:30 and 1:45 p.m. local time on every daytime orbit. The satellite crosses the poles at a very precise location, and then circles around the nighttime side of the Earth, moving over the equator between 1:30 and 1:45 a.m. local time. This type of special polar orbit is called a frozen Sun-synchronous orbit.

It takes work to maintain a frozen Sun-synchronous orbit. Tugged by the Sun and Moon, polar-orbiting satellites gradually drift closer to the equator. Eventually, Aqua’s orbit will shift enough that it no longer follows the afternoon sunlight around the globe. To compensate for gravity’s pull, Aqua’s controllers have to shift the satellite’s orbit toward the pole (right relative to its forward motion at night) every couple of years. Since the thrusters are on the back of the spacecraft, the satellite has to turn to face right so that when the thrusters fire, the satellite moves right.

15:16:00 UTC: Aqua’s instruments begin to notice that Earth is not where it should be and that the satellite’s motion is off. The satellite sends a distress signal to Mission Control.

“Red alarms,” one of the online engineers in contact with the satellite reports over the SCAMA. In the adjoining room, red and yellow grids flash across one of Pawloski’s computer screens. He is expecting the alarms: they mean that the instruments are correctly reporting that the satellite is turning. “Ignore red alarms.” A little more than 35 minutes are left.

If the satellite does not turn quickly enough, Pawloski will abort the maneuver. There has to be time to complete the burn that will shift the orbit and then turn the satellite back around before Aqua crosses into the daytime side of the Earth. Some of Aqua’s instruments are sensitive to solar radiation. They are shielded as long as the satellite faces forward, but when the satellite turns, light and other electromagnetic energy can get into the instruments. Since the shields don’t protect the instruments from the Sun while the satellite is turned during the maneuver, the flight team uses the Earth as a shield, turning the satellite while it is on the dark side of the Earth. The entire maneuver has to be finished and the satellite turned to place the shield between the sensors and the Sun before Aqua comes back around into the light.

At the guidance, navigation, and control station, Blanchard and Nidhiry intensely watch the satellite’s movement. “Halfway through slew,” Blanchard reports with 31 minutes and 52 seconds to go. The turn is on schedule. Conversations begin floating around the room while everyone waits for the satellite to finish its turn.

15:25:09 UTC: Having turned 86.466 degrees to the right, Aqua’s onboard computer notes the next command in its queue: fire the thrusters for 550 seconds (9 minutes, 10 seconds). Propellant flows into the thrusters, and the planned burn begins.

In a third room off Mission Control, Josh Levi and his team of flight dynamics engineers are tracking the burn. They planned the maneuver, and at the end of the day, they will analyze the results to see where the satellite ended up. This is the eighth of nine maneuvers that will together move Aqua a tenth of a degree. This maneuver should move the satellite 6.2 meters to change the orbit by 0.00977 degrees—not quite a hundredth of a degree. It’s a tiny distance, but it is as far as the team can safely move the satellite in the time they have before Aqua returns to the daylight part of its orbit. The last maneuver, number seven, was intended to move Aqua 0.00973 degrees. The actual movement amounted to a change of 0.01002 degrees. Based on these results, Levi adjusted today’s plan to keep the satellite on target.

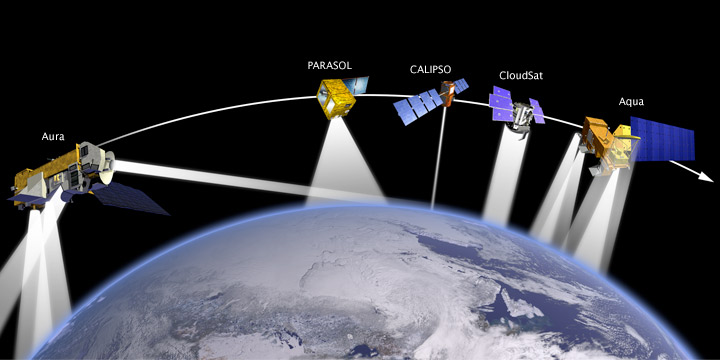

Planning the maneuver is no simple thing. “Aqua doesn’t fly alone,” says Aqua mission director William Guit. Aqua is the lead satellite in the A-train, a constellation of five satellites flying in the same orbit like a train. The idea is to collect data from the same place at about the same time to make comparisons between the instruments easier. Every move that Aqua makes has to be coordinated with the other satellite teams to maintain the constellation. During the two-month period that Aqua makes its nine maneuvers, all of the other satellites have to be adjusted as well, and all that movement has to be coordinated. Communications engineer Frank Wright in Levi’s group coordinates the moves with all of the other teams.

The team also has to coordinate with the various science teams to make sure the maneuver doesn’t affect data during a crucial period like a field campaign. The coordination takes time. This series of maneuvers has taken more than a year to plan, negotiate, and coordinate, and Levi is already thinking about the next set in 2010. But the planning is easier now than it had been in the early stages of the mission, when no one was certain how the satellite would respond to the maneuver commands, and the flight teams had to develop contingency plans for every possible outcome.

Now, the team is comfortable with the maneuvers. Many members of the teams are also on the flight teams for the Aura satellite, another member of the A-train, which is undergoing orbital adjustments in step with Aqua. The day before the maneuver, number eight of nine, the flight dynamics team met with the flight operations team and the Aqua mission director to go over the results of the previous maneuver and present the plan for the next. The flight dynamics team presented their plan for the maneuver, which the operations team would carry out. After six weeks of maneuvers, the process had become so smooth that the meeting flowed quickly. The only debated point had been to decide who was bringing breakfast and whether it should be bagels or donuts.

15:34:19 UTC: Aqua completes its burn and turns off its thrusters.

“149.9. You were right, Jamie.” Command and data handling subsystem engineer Jake Simmons does not say this into the official SCAMA, but turns from his station to announce these results to Pawloski. He is referring to the longitude over which the satellite completed its burn, which tells them where the satellite is. “We all guess how close to predicted we are performing,” Pawloski says. It’s not too surprising that the lead engineer came closest. Pawloski has been on Aqua’s flight team since before the satellite launched in 2002.

15:34:49 UTC: Aqua notes again that there is a large error in its slew angle: in fact, it’s facing the wrong direction entirely. It fires its thrusters for a third time and begins to turn the spacecraft back towards the front.

“Beginning slew back,” Blanchard’s voice reports over the SCAMA. Sixteen minutes 49 seconds left. The tension in the room rises slightly. This time, everyone tracks the turn.

“Slew back half way,” says Blanchard. Eleven minutes, 23 seconds.

A figure on Pawloski’s screen shows that the satellite is 30 degrees away from facing front. “We’re in a race against time,” he explains, watching the figure. The Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) sensor is sensitive to direct light from the Sun. If the satellite is not back to within 20 degrees of facing front by 15:47:23 UTC—the countdown clock will say 4 minutes, 23 seconds—a safety door will automatically close over the sensor, both shielding it from harm and making it impossible to collect data.

Six minutes, 8 seconds: 3 degrees to go.

Four minutes: a number one flashes on Palowski’s screen under a timeline of the maneuver. The satellite had turned itself enough that MODIS’ safety commands did not initiate, but the information is just reaching his screen.

15:46:34 UTC: Aqua has fully turned and is in position to resume its mission of monitoring Earth’s water systems.

The maneuver itself complete, the team has to reset the satellite to get it ready to collect data. When Aqua comes back into view of the communications satellite a few seconds later, they shut off the valve that allows fuel to flow into the thrusters and reset the instrument safety protocols that had been turned off during the maneuver. This done, it only takes seconds for the mission control center to empty.

At 12:20 p.m. Eastern Daylight Time, Aqua mission director, William Guit sends an email to the Aqua and A-train teams:

“EOS Aqua successfully executed its inclination adjust maneuver today.”

Author’s note: Many thanks to the Aqua and Aura flight dynamics and flight observation teams for allowing me to follow them around and pester them with questions during a busy time. Thanks especially to Bill Guit, Jamie Pawloski, Dimitrios Mantziaras, Josh Levi, David Tracewell, and Frank Wright.