AvalancheRunning east to west across the narrow isthmus of land between the Caspian Sea to the east and the Black Sea to the west, the Caucasus Mountains make a physical barricade between southern Russia to the north and the countries of Georgia and Azerbaijan to the south. In their center, a series of 5,000-meter-plus summits (16,000-plus feet) stretch between two extinct volcanic giants: Mt. Elbrus at the western limit and Mt. Kazbek at the eastern. Volcanism fuels hot springs that steam in the alpine air. On the lower slopes, snow disappears in July and returns again in October. On the summit, winter is permanent. Glaciers cover peaks and steep-walled basins called cirques. The remote, sparsely populated area is popular with tourists and backpackers. |

One year after the Kolka Glacier collapsed and partially buried the Russian village of Karmadon, a team of researchers set out to explore the region on foot. The team combined satellite imagery with their first-hand knowledge of the area to investigate the causes of the avalanche and evaluate future hazards. In this photograph Sergey Chernomorets (left), Olga Tutubalina (right), and their field assistants pose on a pile of glacial debris. (Photograph courtesy Alexander Aleinikov) | ||

| |||

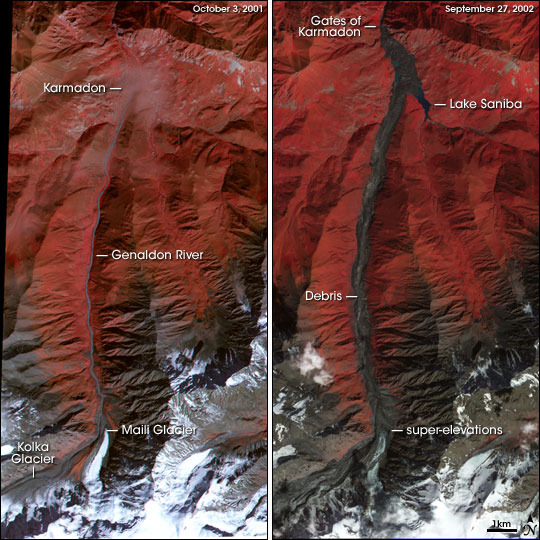

On the evening of September 20, 2002, in a cirque just west of Mt. Kazbek, chunks of rock and hanging glacier on the north face of Mt. Dzhimarai-Khokh tumbled onto the Kolka glacier below. Kolka shattered, setting off a massive avalanche of ice, snow, and rocks that poured into the Genaldon River valley. Hurtling downriver nearly 8 miles, the avalanche exploded into the Karmadon Depression, a small bowl of land between two mountain ridges, and swallowed the village of Nizhniy Karmadon and several other settlements. |

Between the Black and Caspian Seas, the Caucasus Mountains separate Russia (north) from Georgia (southwest) and Azerbaijan (southeast). Elevations reach 5,642 meters (18,511 feet), and glaciers accumulate from heavy snowfall in the steep mountain valleys. Around Mount Kazbek, a dormant volcano, glaciers intermittently collapse, burying the landscape below under rock and ice. (NASA Image by Jesse Allen and Robert Simmon based on MODIS data) | ||

At the northern end of the depression, the churning mass of debris reached a choke point: the Gates of Karmadon, the narrow entrance to a steep-walled gorge. Gigantic blocks of ice and rock jammed into the narrow slot, and water and mud sluiced through. Trapped by the blockage, avalanche debris crashed like waves against the mountains and then finally cemented into a towering dam of dirty ice and rock. At least 125 people were lost beneath the ice. |

When the Kolka Glacier collapsed in September 2002, ice, mud, and rocks partially filled the Karmadon Depression, destroying much of the village of Karmadon. The debris swept in through the Genaldon River Valley (lower left) and backed up at the entrance to a narrow gorge (top center). The debris acted as a dam, creating lakes upstream. This aerial photograph (looking north) was taken only 16 days after the disaster. (Photograph courtesy Igor Galushkin) | ||

| |||

Dmitry Petrakov, Sergey Chernomorets, and Olga Tutubalina have been returning to the site since the disaster. The three have been friends and colleagues for several years. Tutubalina and Petrakov are members of the Faculty of Geography at Moscow State University. She teaches and researches in the Laboratory of Aerospace Methods for the Department of Cartography and Geoinformatics, and he is a researcher in the Department of Cryolithology and Glaciology. Chernomorets is the General Director of the University Centre for Engineering Geodynamics and Monitoring in Moscow. The combination of backgrounds made the team uniquely qualified to study the Kolka disaster. In the year following the event, they made five trips to the Russian Republic of Ossetia in the central Caucasus. They wanted to figure out exactly what had happened that day and to forecast what might happen in coming weeks, months, and years at the site. |

This pair of satellite images, taken before and after the collapse, shows the vast extent of the disaster. Debris and ice filled the Genaldon Valley from the Kolka Glacier Cirque to the Gates of Karmadon—a distance of about 18 kilometers (11 miles). (Images by Robert Simmon based on ASTER data) | ||