| |||

If someone had asked professional yachtswoman and meteorologist Adrienne Cahalan to name her top weather worries before she set out in February 2004 to attempt to break the record for the fastest round-the-world sailing trip, she might have hauled out a list of concerns as long as the list of supplies that a 13-person crew would need on a multi-week journey. She might have said she was worried about getting stalled in the “horse latitudes” around 30 degrees, where surface winds can disappear for days at a time. She might have mentioned the threat that a fierce gale would hammer their 125-foot catamaran—Cheyenne—into an iceberg in the Southern Ocean off Antarctica. She might have listed the “doldrums” at the equator, where sailors must chase weak and fickle surface winds while navigating a maze of daily thunderstorms fueled by the intensity of the Sun’s most direct rays. |

Adrienne Cahalan was the navigator aboard Cheyenne during the catamaran’s recording-breaking, round-the-world trip in the spring of 2004. (Photograph copyright Thierry Martinez) | ||

| |||

Cahalan would have been thinking of these things because as the crew’s navigator, it was her job to worry about the weather. As they crisscrossed the planet, she would combine weather briefings that arrived every few hours via satellite with real-time, local conditions to route Cheyenne as quickly and safely as possible from the race start line in the English Channel, through each of the world’s oceans, and back to the start line. Among the weather phenomena Cahalan would not have worried about was an Atlantic Ocean hurricane. After all, who worries about hurricanes in February and March? Little did Cahalan know that in addition to their record-breaking pace, she and the crew of Cheyenne would end up being both helped and hindered along their journey by some record-breaking weather—a storm that looked suspiciously like a hurricane where there was no known record of a hurricane before. Where the Hurricanes Aren’tIn the Atlantic Ocean north of the equator, hurricane season officially begins in June and is over by the end of November. In the Atlantic Ocean south of the equator, there is no hurricane season because, as any meteorologist will tell you, there are no known records of hurricanes. |

The maxi-catamaran Cheyenne encountered some unprecedented weather on its record-breaking circumnavigation in 2004. In this photo, some of the crew are standing in the rear (aft) portion of the left-hand (port) hull of the boat, wearing their bright red, weatherproof gear. (Photograph copyright Thierry Martinez) | ||

| |||

“Hurricanes require a perfect blend of conditions,” explains research meteorologist Marshall Shepherd, of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center. Waters must be warm, wind shear must be low, and a disturbance, such as thunderstorms, must jump-start storm formation. “The shear component is particularly detrimental,” says Shepherd. “If the wind increases too quickly with altitude or changes direction, the hurricane is torn apart before it can organize.” With its cooler waters, frequent wind shear, and lack of seedling thunderstorms, the South Atlantic just isn’t a place where scientists or sailors keep watch for hurricanes. When Cahalan and her crewmates set out on Cheyenne in February 2004, they would never have guessed that their round-the-world sailing record would coincide with some record-breaking weather—the first verifiable account of what appeared to be a hurricane in the South Atlantic Ocean. |

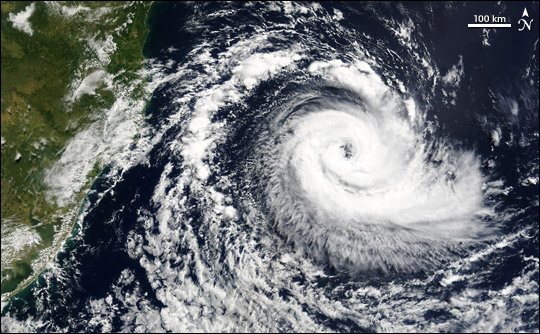

Hurricane Catarina—the first verifiable hurricane ever recorded in the South Atlantic—spiraled off the coast of Brazil on March 26, 2004. The storm upset weather patterns in the southwestern Atlantic, hindering Cheyenne’s round-the-world trip. (NASA Image courtesy Jacques Descloitres, MODIS Rapid Response Team at NASA GSFC ) | ||