If you want to set up a scientific station at the bottom of the world, who would you send? Eighteen “crazy men and a dog,” of course.

The men were a collection of engineers, scientists, and support personnel. The dog, named Bravo, was someone’s pet, and he allegedly had a wonderful time.

The South Pole team soaked up the sunshine after six months of darkness. (Courtesy of Bob Benson.)

Men and dog were hired to establish a science base in one of the most remote places on Earth. Welcome to Operation Deep Freeze and the creation of the Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station.

Just out of college, Benson was one of the youngest members of the South Pole team. (Courtesy of William McPherson, NSF.)

They toiled in the shadow of some of history’s most famous explorers, but they weren’t there for the glory. They were there to begin exploring Earth and space from a unique position. When they finished, they had established the first permanent science laboratory at the South Pole. Their famous predecessors would have been astonished.

Those “crazy men“ included a young graduate student from Minnesota. Robert Benson, age 21, was one of the youngest members of the science party. For him it was a glorious, sometimes funny, adventure and the first step on a scientific journey that would lead him through five decades at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center.

Though retired now, Benson is still an active emeritus scientist. He is also among the last surviving founders of the Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station (now operated by the National Science Foundation). More than half a century later, he remembers the names, sorts the photographs, and recalls the experience with astonishing clarity.

The golden age of world exploration wound down in the beginning of the 20th century with a series of expeditions to the Antarctic. Ernest Shackleton attempted and failed to reach the South Pole in 1908. Robert Falcon Scott made it in 1912, only to find a Norwegian flag already planted there by Roald Amundsen. Scott’s team died on the return.

After World War I, those with an itch to explore new territories had a new tool: the airplane. Rear Admiral Richard Byrd flew three expeditions to Antarctica and became the first to fly over the Pole. Up to that point, it was mostly a place for adventurers and explorers. Little science was done there.

Rear Admiral Richard Byrd (left) led most of the United States' early airborne expeditions to Antarctica and the South Pole. (Courtesy of U.S. Navy and National Science Foundation.)

Then came the International Geophysical Year (IGY). Scientists from around the world designated the period from July 1957 through December 1958 to be a time for international collaborative efforts to study our planet. As part of the effort, the United States pledged to build a permanent station at the geographic South Pole.

At the time, Bob Benson had just finished his bachelor’s degree in geophysics at the University of Minnesota. He was keenly interested in physics and astronomy, and he put in an application to go to the South Pole. (His older brother, Carl, was a glaciologist and kept making expeditions to Greenland because science is what the Bensons did.) Bob Benson was initially told that his IGY application was too late; all of the positions were filled. But a few weeks later, he received a telegram that a slot had opened. If he wanted it, he had better pack immediately.

“I had just started my graduate work in physics,” he said. “I knew I would gain experience in several areas of science related to the polar regions, and I knew it would be a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity.” Professionally speaking, the choice was easy. But he also admits he was interested for the sheer romance of the place.

Though the U.S. Navy SeaBees dug out the foundations and constructed most of the buildings, the South Pole team had to build barracks before settling in for science. (Courtesy of Bob Benson.)

Benson recalled that everyone else on the team had gone through psychological and psychiatric testing to make sure they would not commit suicide or homicide while being confined to a restricted space for six months without sunlight. It was too late for Benson to take those tests, so he was interviewed by Willie Hough—the person he would be working closely with at the South Pole—who felt that Bob would be OK.

The science party was not first on the scene. The foundations of the camp were dug out by the SeaBees, the U.S. Navy’s construction engineers, and nearly all the buildings were up by the time Benson arrived. The task for the scientists was to put the finishing touches on the barracks and the base, and then turn it into a permanent, working scientific station. They were to start conducting research that first winter. It would not be easy.

Benson’s adventure began in the fall of 1956. He went first to Boulder, Colorado, to learn how to interpret ionospheric data. Next he went by air to Christchurch, New Zealand, where the United States maintained (and still does) an Antarctic supply and administration station. From there, he was supposed to fly to McMurdo, the base set up by Byrd on the Antarctic coast. But it was not to be. Because of unusually warm weather, some of the ice on the runway had melted, forming potholes. Instead, Benson and colleagues traveled to Antarctica by ship.

Then they got stuck at McMurdo because the runway still was not frozen enough. People had to shovel snow into the potholes, and then let it refreeze and harden enough for planes to land. It was not a minor matter. Most of the winter-over group was already at the South Pole, but they were running low on supplies.

The U.S. Navy used R-4D planes outfitted with skis to shuttle men from coastal bases to the South Pole station. When they couldn't land with supplies, the U.S. Air Force dropped them from C-124 Globemasters. (Courtesy of U.S. Navy and NSF.)

The scientists finally took off for the Pole in a Navy R-4D, the military version of the legendary DC-3. The plane was rigged for landing on skis. “The plane was so fully loaded that the maximum altitude was about 10,000 feet, which is the same altitude as the Pole,” Benson recalled. “You just fly straight and the Pole comes up under you.”

The airplane’s load was so finely balanced that when one passenger moved to the back to get a loaf of bread, the plane started losing altitude. He was chased back to the middle of the plane. Everyone huddled around a gas tank. No one wore seat belts.

When they got to the South Pole, the pilot feared he would not be able to take off again, so he kept the engines running. The temperature was -20° Fahrenheit (-28° Celsius), and it was February 12, 1957.

The long, dark polar night began with sunset on March 21, 1957. (Courtesy of Bob Benson.)

The Sun would go down for good on March 21. Benson quickly learned about living on the edge.

On his fatal trek to the Pole, Robert Scott described it dramatically. In the journal that was found with his frozen body, Scott wrote: “Great God, this is an awful place.”

The Antarctic is the coldest, driest, windiest place on Earth. The continent is nearly twice the size of Australia and almost entirely covered with ice. While Antarctica has huge mountain ranges, they are mostly buried in ice that is almost two miles thick. Though snow and ice abound, the area is technically a high desert. The Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station sits 2,900 meters (1.8 miles) above sea level on a vast, flat plateau.

It is dark for half of the year. When the Sun is up, the sky and the ice are bright and stark, stretching out forever in the crystal air. The place is as breathtakingly beautiful as it is dangerous.

How cold was it in 1957? During construction, with temperatures hovering at about -60° Fahrenheit (-51° Celsius), the bubble in the carpenter’s level would not stay liquid. Someone had to put the level inside his coat, run inside, and let it thaw sufficiently to make it useful again. He then ran back outside before it refroze.

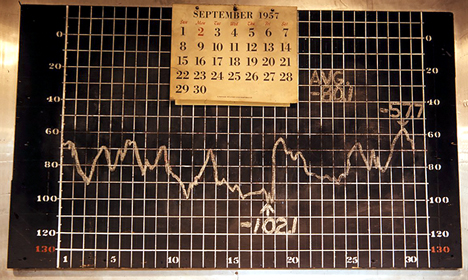

The South Pole party logged temperatures daily, and they never got close to the melting point. The record low for the winter was set just a few days before sunrise. (Courtesy of Bob Benson.)

The science party kept track of the temperatures throughout the year, and the mercury never rose above zero. On September 18, 1957—near the end of the austral winter and just before sunrise on September 23—the temperature dropped to -102.1°F (-74.5°C), the record for that year.

The science operation was run by geographer Paul Siple, a legend in Antarctic exploration who had made his first trip to the frozen continent as a Boy Scout accompanying Admiral Byrd in 1928. By the time Siple was leading the expeditions, he had a beard so long that it would freeze to the zipper of his parka. He had to stand over a room heater to thaw it before he could take his coat off.

After the Sun rose again in September, the team started to dig out from the winter accumulation of drifted snow. (Courtesy of Bob Benson.)

The buildings at the first South Pole Station all stood above ground, but they were connected by covered tunnels. Temperatures in the tunnels were about -50°F (-46°C). One building was intentionally located 200 feet away from the others. It was the Jamesway (or Quonset hut) that would be used in case the worst happened (ironically, fire). Everyone had a duffle bag full of what they would need in case they “lost the station.”

There are things you can do at the South Pole that you can’t do—or do as well—anyplace else on the planet.

For instance, telescopes can track celestial objects for long periods of time from exactly the same place through air totally devoid of light and particle pollution. Because the air is so dry, it is also possible to listen to the sounds of the Big Bang—cosmic microwave background radiation—nearly 14 billion years old. The air is so clean—possibly the cleanest on the planet—that it can be used as a baseline to watch changes in the atmosphere on this planet.

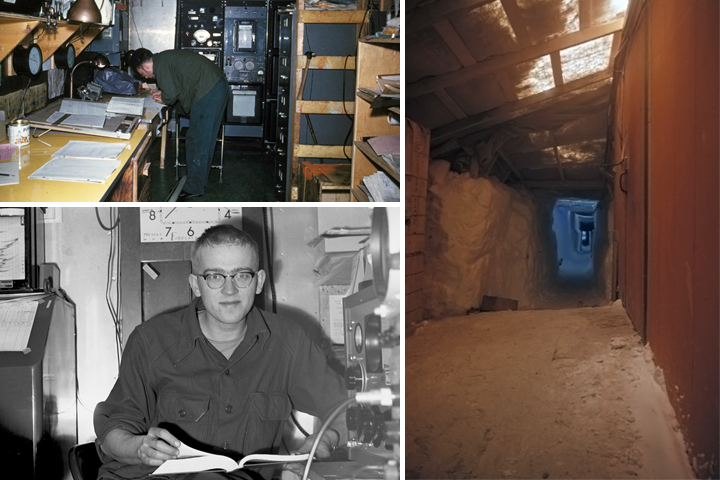

Science observations were recorded in the meteorology station (top left), while the seismometers were connected to the building by a 1,000 foot tunnel through the ice (above). Without sunlight or room to roam, Benson (lower left) and others had plenty of time for reading. (Courtesy of Bob Benson and Cliff Dickey.)

Bob Benson helped set up two science stations in this natural laboratory. A geophysicist was using a seismometer to plot earthquakes from around the world—the Pole is an excellent place to do that—and he needed help. Benson was drafted. The seismometer recorded not only earthquakes—including many from as far as the Aleutian Islands—but the cycles of the electric generators at the station.

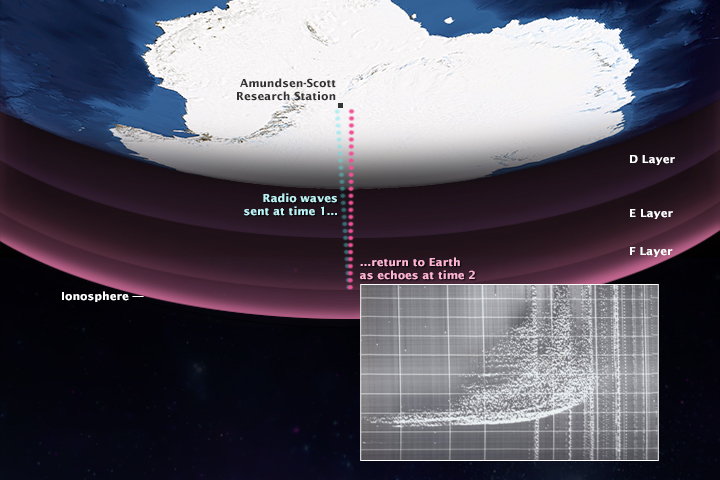

His other job was to monitor and study the ionosphere, the electrically charged part of the atmosphere above 60 kilometers (40 miles) altitude. He used a device called an ionosonde, which sent radio waves of various frequencies toward the atmosphere. From the received echoes, he could measure the height and density of the ionosphere.

Benson analyzed echoes of radio waves reflected from the upper atmosphere in order to determine the height and density of the ionized layers, as shown (inset) in this 1957 ionogram. (Illustration by Joshua Stevens, NASA Earth Observatory. Data photo courtesy of Bob Benson.)

Full of particles energized by sunlight, the ionosphere reflects radio waves. But in 1957, some scientists wondered if the ionosphere would gradually disappear when the Sun went down for six months. That posed a problem because the South Pole team was planning to communicate with the rest of the world by bouncing radio signals off of the ionosphere. If they could not use these radio techniques, the station would be totally isolated during the winter, adding dramatically to the danger.

New Jersey teenager Jules Madey used his ham radio antennas to help the South Pole team keep in touch with colleagues and relatives in the United States. (Courtesy of Bob Benson.)

Fortunately, they found that the ionosphere was intact despite the darkness, and it allowed them to set up a unique radio relay system. They sent out transmissions to see if anyone would hear them, and many ham radio operators responded—but none more regularly and reliably than 16-year-old Jules Madey of Clark, New Jersey. Madey and his 13-year-old brother, John, captured those long-distance radio signals. With the enthusiastic support of their parents, the Madeys built a 110-foot radio antenna in their backyard. Soon the South Pole science team came to rely on those two teenagers (and a few other amateur radio operators) to place long-distance telephone calls so they could communicate with family and friends in the United States.

Besides learning to use the ionosphere for radio relay, Benson and colleagues discovered that the ionosphere followed a 24-hour periodicity, even without sunlight. It was the first of many ionospheric observations in Benson’s career.

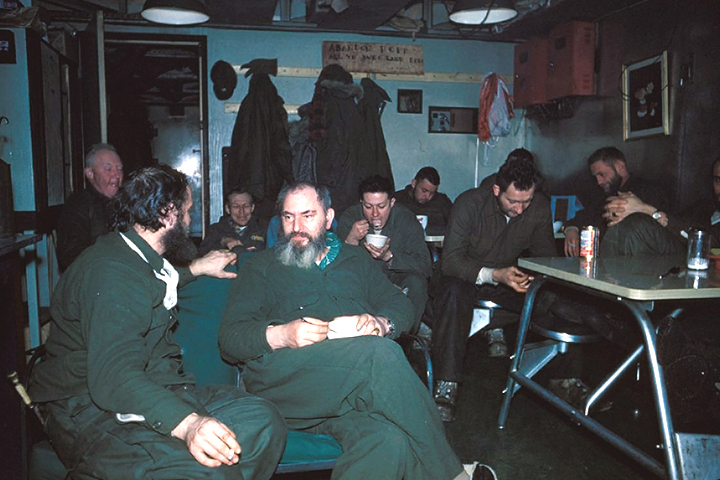

Life at the first South Pole station demanded resourcefulness and creativity, which was good for the body and the mind.

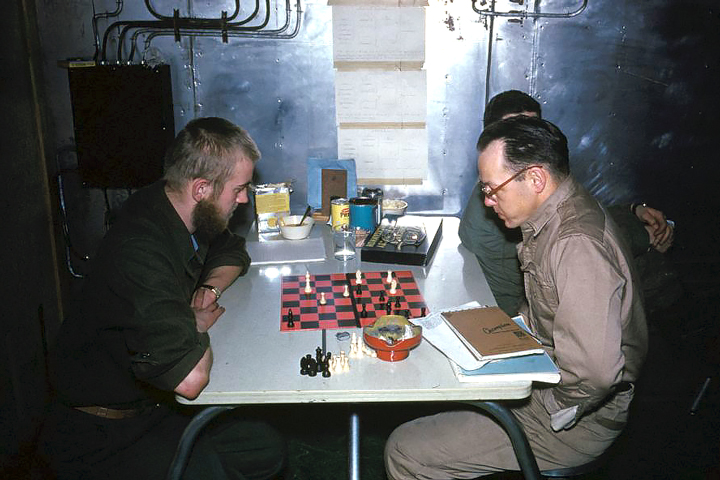

Bob Benson (left) plays chess with meteorologist Ed Flowers in the mess hall. (Courtesy of Bob Benson.)

One of Siple’s rules was that almost nothing should be thrown away. You never know when you might need something, he insisted, and it was thousands of miles to the nearest hardware store. Part of the base consequently looked like a junkyard.

Within weeks of settling into the base, people grew immune to each other’s germs and stopped getting sick. That left the base with a surplus of tongue depressors—enough to make ice cream on a stick. However, one night during an outdoor picnic—it was 60 degrees below—someone ate his ice cream and then discovered that he had also eaten half of the depressor. It all tasted the same at that temperature.

In the barracks, they held frequent lectures on what each researcher was working on. They also showed Hollywood movies a few times a week on a 16-millimeter projector. There was not much else to do at night. They burned their garbage every full moon, though no one knew why. It just seemed cool.

Paul Siple (center) and the rest of the team enjoy some ice cream before watching a movie—two of the few creature comforts from home. (Courtesy of Bob Benson.)

An outhouse was placed right at the South Pole as a joke, but it was never used. There was also an indoor outhouse in one of the buildings, but the temperature below the seat was -40 degrees. The medical doctor, Howard Taylor, devised a cover to go over the hole so at least a person could start with a toilet seat at room temperature. One man with an odd sense of humor stacked magazines next to the toilet in case anyone stayed long enough to read. No one did.

Bathing was another issue. Water wasn’t the problem: the men had miles of it frozen beneath them. Everyone was required to work several hours per week in the “snow mine.” That snow was carried in a burlap bag into the living quarters and melted with heat that bled off the generators. Showers were quick.

During his great adventure, Benson took hundreds of photographs, some of them with a rudimentary pinhole camera that he had made at the station. Once a National Geographic photographer, Tom Abercrombie, visited and encouraged Benson to submit one of his pinhole-camera photos to the magazine. It was a four-day time exposure of the Moon circling the station, and it was good enough to make a two-page spread.

Bob Benson used a pinhole camera to take this long-exposure photograph of the Moon’s path across the sky over several winter nights. (Courtesy of Bob Benson.)

After 10 months in Antarctica, Benson returned to the University of Minnesota to obtain a master’s degree in physics. He then went back to cold extremes, earning his doctorate in geophysics from the University of Alaska-Fairbanks. After one year of teaching in the astronomy department at the University of Minnesota, he then spent five decades at NASA Goddard studying the ionosphere.

Like everyone else who has ever been to the South Pole, Benson considers the trip one of the high points of his life. But he has never returned. Even crazy men eventually become wiser with age.

Though he loved his adventure, Bob Benson, now age 80, has never been back to Antarctica. (Deborah McCallum, NASA.)