Without people, a yearly fire season in the Amazon Rainforest would be almost as unlikely as a hurricane season in Antarctica. Today, however, the Amazon is a frontier, and settlers are burning hundreds of thousands of acres of rainforest each year for cattle pasture and farms. Accidental fires degrade thousands of acres more. |

|||

| |||

The decisions about how the Amazon will be developed will mostly be made by Brazil, where 62 percent of the remaining forest is located. But on an increasingly crowded and climate-conscious planet, it’s inevitable that a human-made fire season in the world’s largest remaining rainforest—a treasure trove of species diversity and, if burned, a large source carbon dioxide emissions—will attract global attention. Amazon attractionAtmospheric scientist Ilan Koren of the Weizmann Institute of Science is among those whose attention gravitates toward the Amazon. The interest is part professional, part personal. After finishing high school and completing the three years of compulsory service in the army required by all Israeli young people, Koren says, “The last thing one wants to do is study.” Instead of heading straight to college, Koren set off with a friend to travel around the world. After mountain climbing in the Andes, they decided to end their tour with a motorcycle trip through the Amazon. |

Naturally occuring fires are rare in the Amazon, but each year, people set thousands of fires to clear the rainforest and maintain existing farmland and pasture. This human-made fire season affects biodiversity, air quality, and the global climate. (Photograph © 2003, Greenpeace/Daniel Beltrá.) | ||

Bumping their way along dirt roads through the jungle and sleeping in tents, it took them about two months to get from Caracas, Venezuela, to Belem, Brazil, at the mouth of the Amazon River. “It seems like there are two reactions to the Amazon,” Koren says. “Either you cannot stand it because it is so humid and hot, with all these insects and strange animals, or else you fall in love with it. And I really fell in love with it—the humidity, the hot weather, everything.” A natural cloud laboratoryThe Amazon is also a fascinating natural laboratory for Koren’s primary research interest: clouds. “The clouds in the Amazon are special. The forest emits huge amounts of humidity,” Koren explains, “which creates a surrealistic view of mist and clouds forming from tree level all the way to the upper atmosphere—more than 10 kilometers up.” When the air over the Amazon is clean, the clouds that form over the forest are so like maritime clouds that scientists have referred to the Amazon as “the Green Ocean.” |

Atmospheric scientist Ilan Koren is as at home collecting data on top of a 4,300-meter (14,000-foot) Colorado mountain as he is in front of his computer modeling the interactions between smoke and clouds. His love of the Amazon developed during a 3-month motorcycle trip he and a friend took through the area when he was in his 20s. (Photograph courtesy Lorraine Remer, NASA GSFC.) | ||

| |||

The hundreds of thousands of fires that blaze during the dry season complicate that picture. For several years now, Koren has been collaborating with a team of scientists at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, using use satellite data from a sensor called MODIS (short for Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer) to better understand how smoke changes clouds in the Amazon. Smoke changes the size and number of cloud droplets, which affects their brightness. It also warms the smoke layer, which stabilizes the atmosphere and suppresses updrafts that fuel cloud formation. Clouds are better at reflecting sunlight back into space than smoke, so fires in the Amazon likely allow more solar energy than normal to enter the Earth’s climate system. |

The unbroken canopy of the Amazon Rainforest releases so much water vapor into the air that the clouds over the forest are similar to those that form over the ocean. This satellite image from June 11, 2002, shows a uniform blanket of clouds interrupted only by the Amazon River and several of its tributaries. (Satellite image courtesy MODIS Rapid Response Team.) | ||

| |||

When he first started studying these questions, Koren was focused on how smoke influenced clouds on a day to day basis. So, initially, he didn’t pay much attention to whether the amount of burning was changing over time. That began to change in 2005. A bad year or a long-term trend?“We had been working with the MODIS aerosol and cloud data since 2000, and we had noticed that there are large fluctuations [in smoke] between the years. Some years are relatively clean, and the next it is polluted. But in 2005, we began to be quite worried. We saw that it was so much more polluted, and we thought that we had to do something to try to understand what was happening,” Koren explained. “We wanted to know if that was just one bad year, or if fires and smoke in the Amazon were increasing.” |

During the burning season, smoke often covers huge portions of the Amazon. Isolated towers of cumulus clouds poke through the dense layer of smoke in this photograph taken from an airplane. (Photograph courtesy Ilan Koren.) | ||

| |||

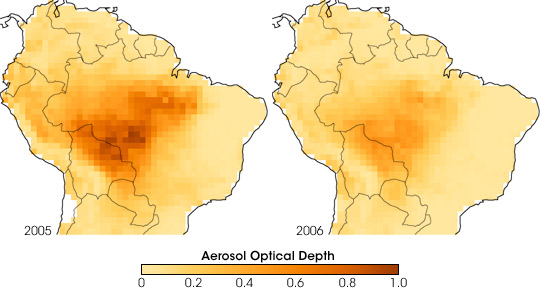

“We decided to use two independent types of data. We used aerosol data from MODIS from 2000 to 2006 to measure smoke, and daily fire counts from NOAA’s AVHRR [Advanced Very High Resolution Radiometer] from 1998-2006.” says Koren. “We selected the entire biomass burning area, the heart of the Amazon where most of the fires occur, and we looked at daily and monthly averages in the number of fires and the amount of smoke. We compared the average of the dry season—August to November—of each year.” “We also wanted to see it spatially,” he explains, “so we took each one degree of the data [an area of about 12,000 square kilometers] and mapped the trends over time.” What they saw surprised Koren. Since 1998, the number of fires in the dry season had nearly doubled. Smoke aerosols had increased by 60 percent. “We expected to see some increase, but such a strong increase was quite a shock.” |

Since 1998, the number of fires occurring during the Amazon fire season nearly doubled. Smoke increased nearly 60 percent between 2000 to 2005. In 2006, the trend reversed, with both fires and smoke dropping off significantly. (Graph by Robert Simmon, based on data from Ilan Koren and Karla Longo.) | ||

| |||

Equally surprising, though, was that in 2006, the upward trend suddenly reversed. The fire counts and smoke are among the lowest in the record. Why was 2006 so different? And what would 2007 bring? |

After record burning in 2005, smoke levels dropped abruptly in 2006. Dark brown indicates high smoke aerosol concentrations, while light yellow indicates clearer skies. Smoke concentrations are higher in the southern Amazon, the forest’s agricultural frontier. (Maps by Robert Simmon, based on MODIS data from Ilan Koren.) | ||

Burning Falls in 2006, Rises in 2007 | |||

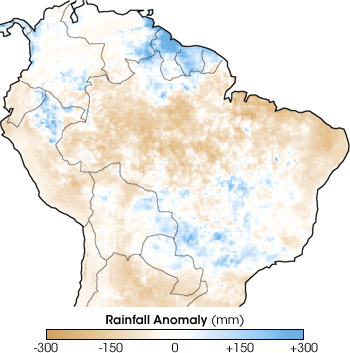

The dramatic drop in fires and smoke in 2006 may partly result from the devastation of 2005. Koren and his colleague Lorraine Remer collaborated with Karla Longo, a scientist at the Brazilian Center for Weather Forecasting and Climate Studies, who explained that in 2005, the annual dry season in Peru, Bolivia, and southwestern Brazil had ballooned into an unrelenting drought. Agricultural fires on the Amazon frontier invaded adjacent forests on a large scale. |

|||

The urgent situation spurred unprecedented collaboration between government agencies, civil organizations, and scientists to identify and control fires. The success of this initiative may have carried over in 2006. For example, for 75 days in 2006, the Public Ministry of Acre prohibited burning in eastern Acre, where the damage from out-of-control fires in 2005 was especially severe. The Amazon in the Global MarketplaceSuccessful regulation is probably not the whole story, however. Several scientists, journalists, and environmental groups have pointed out the link between Amazon deforestation rates and the price of global commodities, mostly soy and beef. In the 1980s and 1990s, much of the deforestation in the Amazon resulted from many small clearings by subsistence farmers. But increasingly, deforestation is driven by industrial-scale cattle ranches and to a lesser extent, soy farms. Regulation and cooperation for controlling fires may have stepped up in 2006, but the price of soy was also down, lessening the economic incentive to clear forest for soy farms. |

The dry season of 2005 marked the end of an intense, multi-year drought. In January—the rainiest month of the year in much of the western Amazon—precipitation was far below average (brown areas) across much of the Amazon basin. Many agricultural and land-clearing fires got out of control and damaged nearby rainforest. (Map by Robert Simmon, based on Tropical Rainfall Measuring Mission (TRMM) data from the Goddard DAAC.) | ||

| |||

The fingerprint of the global market’s influence on Amazon deforestation seems to have been left on the 2007 fire season, as well. After the 2006 lull, the fires and smoke in 2007 were worse than any year in Koren’s 1998-2006 study period. Via email, William Laurance, of the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, wrote, “Most folks are attributing the heavy deforestation in late 2007 (or more specifically, the high incidence of fires) in places like Mato Grosso and Para [states in southern Brazil] to high soy and beef prices.” |

Increasingly, Amazon deforestation is the result of industrial-scale cattle ranches (top) and soybean plantations (below), rather than small farms. (Photographs © 2004 Greenpeace/Alberto Cesar and © 2006 Greenpeace/Nilo D’Avila.) | ||

| |||

Sugar Cane ControversyKoren says another possible—and more controversial—reason for the increased burning could be that Brazilian farmers have stepped up sugar cane production in response to the global boom in the biofuels market. Ethanol fuel is made from the sugar in the plants’ tall, bamboo-like stems. To make harvesting easier, which reduces manual labor costs, sugar cane fields are burned prior to harvest to remove the plants’ leaves. Many growers have agreed to phase out burning over the next decade. Until the switch to mechanized harvest is complete, however, smoke pollution will continue to be a problem in Brazil’s sugar cane growing region. The industry is well established in the savannas and grasslands south of the Amazon, where the climate and soil are more suitable for sugar cane cultivation. |

Koren and his colleagues measured increasing concentrations of smoke over the Amazon from 2000 to 2005, followed by a big drop in 2006 and a dramatic spike in 2007. (Graph by Robert Simmon, based on MODIS data from Ilan Koren.) | ||

| |||

In news reports, Brazilian President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva has dismissed the possibility that growth in sugar cane production for biofuels is causing significant new deforestation in the Amazon Rainforest, citing the unsuitable climate. Even so, Koren thinks, it’s possible that previously cleared lands—cattle pasture or soy farms—along the southern Amazon frontier were converted to sugar cane in 2007, contributing to more fires and smoke. Hope for the AmazonDespite the upswing in fire activity in 2007, the 2006 drop offers hope that a combination of effective regulation and market-based incentives for conservation will allow Brazil and other Amazon countries to improve their economies without sacrificing a crucial ecological and climate-stabilizing resource. It is those moments of hope that keep Koren motivated, despite the fact that the career he has chosen makes him intimately familiar with so many of the world’s worst environmental problems. |

Sugar cane is widely grown for biofuel in southern and southeastern Brazil. To reduce labor and processing costs, the leaves of the plants are burned off prior to harvest of the canes. Whether the increase in fires and smoke in 2007 could be tied to the conversion of forest or existing agricultural land into sugar cane plantations for biofuel has been a controversial question. (© 2007 UN Photo by Eskinder Debebe.) | ||

| |||

“You do see depressing things. But you just try your best to show people what is happening [in the world] and influence things the best you can. Then you just have to be optimistic. You know, there is a very strong link between scientists and artists. The link is that you have to be very creative, always trying to ‘think outside the box.’ And you are not paid well,” he says with a laugh. “Which means you really have to love it.”

|

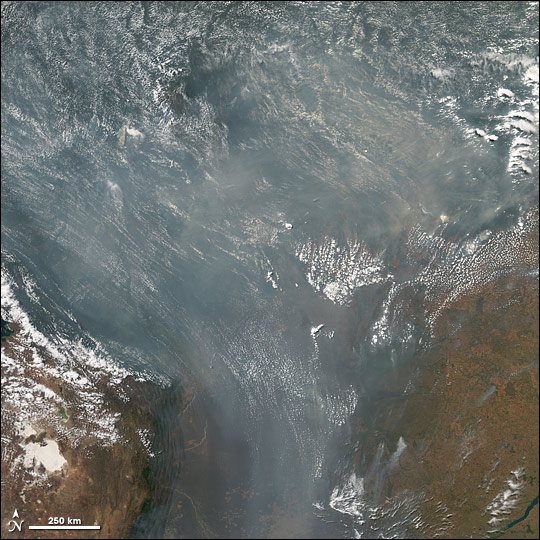

After falling off in 2006, fires and smoke increased again in 2007, perhaps spurred by increases in cattle and soybean prices on the global market. Smoke completely covers thousands of square kilometers in this MODIS image acquired September 9, 2007. (NASA image by Jesse Allen and Robert Simmon, based on data from MODIS.) | ||