Water levels on the Mississippi River normally decline in the fall and winter, but not by nearly as much as they did in October 2022. Lack of rain in the Ohio River Valley and Upper Mississippi River Valley in recent weeks caused river water to drop to levels not seen in more than a decade along key parts of the river. The low water levels are slowing barge traffic and raising concerns that saltwater intrusions in the Lower Mississippi could affect water supplies.

The Operational Land Imager-2 (OLI-2) on Landsat 9 captured this natural-color image of the parched river on October 7, 2022. The image shows backed-up barges north of Vicksburg, Mississippi. At times, well over 100 towboats and barges waited due to a temporary river closure caused by barge groundings and dredging work, according to news reports. The towboats and barges are strung together into groups that vary in size but can easily be 1,000 feet (300 meters) long and 100 feet (30 meters) wide.

The map above shows how wet the soil was on the same day the Landsat 8 image was acquired. Using data from the Crop Condition and Soil Moisture Analytics (Crop-CASMA) product, the map shows soil moisture anomalies on October 7, 2022, or how the water content in the top meter (3 feet) of soil compared to normal conditions for the time of year. Brown areas were drier; blue areas were wetter. Crop-CASMA integrates measurements from NASA’s Soil Moisture Active Passive (SMAP) satellite and vegetation indices from the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) instruments on NASA’s Terra and Aqua satellites.

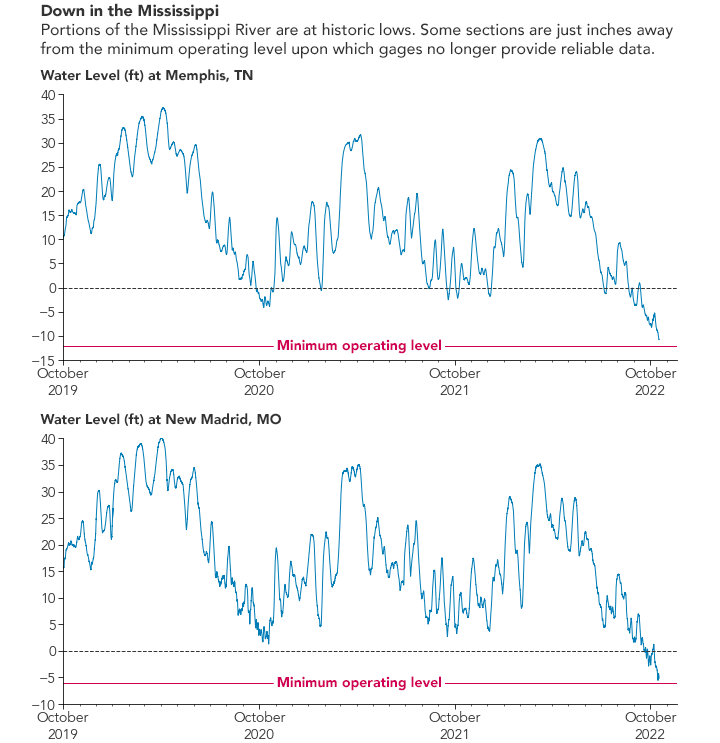

River levels at Vicksburg had dropped to 0.66 feet (0.20 meters) by October 20, a low level but still well above the record low of -7.00 feet in 1940. However, farther upstream in Memphis, the river level dropped to -10.79 feet on October 17, 2022, the lowest level recorded at the site since the start of National Weather Service records there in 1954.

At New Madrid, Missouri, water levels had dropped to -5.1 feet on October 20, just slightly above the minimum operating level of the gage. Water levels, or “gage height,” or “river stages” do not indicate the depth of a stream; rather, they are measured with respect to a chosen reference point. That is why some gage height measurements are negative.

A lack of rain over a very broad area is the main reason water levels have dropped so low, explained Tennessee State Climatologist Andrew Joyner. “It doesn't take long for water levels to go down given a lack of rain over such a large area,” he said.

Downstream, in the lower part of the river, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers is dealing with the intrusion of saltwater into the lower reaches of the river. Normally, the flow of the river prevents saltwater from the Gulf of Mexico from moving very far upriver, but the river is so low that a wedge of saltwater has crept northward and threatens intakes used for freshwater supplies. To prevent saltwater from getting farther upstream, the Corps began construction on an underwater sill in Myrtle Grove, Louisiana, on October 11.

Forecasting from the National Weather Service Lower Mississippi River Forecast Center calls for water levels to drop even lower at several points along the river in coming weeks. In many cases, they expect water levels to drop even lower than they did in 2012, 2000, and 1988—other years when water levels hit unusually low levels.

What will happen beyond a few weeks is less clear. “Looking at one- and three-month forecasts, it looks like there are equal chances of above or below average rainfall,” Joyner said. “If we end up with average rainfall, conditions might not worsen, but it also won't lead to improvements.”

NASA Earth Observatory images by Joshua Stevens, using soil moisture data from Crop Condition and Soil Moisture Analytics (Crop-CASMA), Landsat data from the U.S. Geological Survey, and data from the National Water Information System. Story by Adam Voiland.