By Lora Koenig (as told to María José Viñas)

All the members of our team are now in Kulusuk, Greenland. We’re quite isolated in this tiny village but we have a whole team behind us, making sure we get our stuff on time. The people in town are helping us a lot, too (hence the title of this blog post), letting us drive their vehicles or use their buildings to organize our gear.

We have almost all our equipment — except for a couple of important items, like the generator that runs the drill and the ethanol we will use to free the drill if it gets stuck inside the ice. Both items should arrive on Saturday.

When I was in Reykjavik’s airport, I suddenly remembered I had forgotten a backup set of drill cutters (the bits that cut into the snow as the drill goes down) — they were inside a little box that slid under my car’s seat while I was driving to the airport in Maryland. Fortunately, my mom came to the rescue, recovered the box and sent it expedited to Greenland — it should also arrive to Kulusuk on Saturday’s flight. Here’s a big thanks, mom!

Our put-in date continues to be April 1 — in the case not all of the missing gear arrived on Saturday, half of the team might still go to the drill site that day, while the other half will wait for the remaining equipment. We’ll make a firm plan tonight. Meanwhile, the team and I are testing our gear… and enjoying our surroundings! Kulusuk is a small town built around an airstrip and surrounded by big mountains. Its few hundred inhabitants mostly work in the airport, or are hunters or fishermen.

The weather’s beautiful, there’s not a cloud in the sky, and we’ve seen the northern lights — we have great photos that unfortunately, we can’t send right now. (I’ll send pictures as soon as possible, after fieldwork is done and we have a better Internet connection.)

—-

[Note: This blog post was written by María-José Viñas, based on a telephone conversation with Lora Koenig. Normally, Lora writes her own posts and María-José edits and publishes them. However, there is no Internet at Lora’s hotel in Kulusuk until a repairman arrives on Saturday’s flight.]

By Lora Koenig

As I write this post, on Tuesday, March 26, our team is spread across the globe. I am at Dulles airport near Washington, D.C. waiting to get on a plane that will fly through the night to Iceland, and then onto Kulusuk, Greenland, tomorrow. My gear includes a thick parka, boots, cloths, medicine (just in case) and even some chocolate for Easter, all packed in a nice water-tight bag so no snow will get in it. Jay, Clem and Ludo are already in Kulusuk and Rick is waiting in Iceland to get on the same plane that will take me to Greenland tomorrow.

How did we all get so spread out? Well, it was mostly caused by the unpredictably of weather canceling flights and the limited number of flights into Kulusuk (there are only two each week — on Wednesdays and Saturdays).

To figure out our logistics, we have to start with our put-in date that is scheduled for April 1. “Put-in” is when we go from Kulusuk to our field site on the ice sheet to put in our camp and start the science. A put-in date of April 1 means we all need to arrive in Kulusuk at least one flight before the connection flight, to give us a cushion. Rick and I will arrive on the March 27 flight, which is the last flight with a cushion. We would have all arrived on this flight but the Easter Holidays threw a wrench in our schedule: all services will be closed in Kulusuk from March 28 to April 2. So Jay, Clem and Ludo arrived early to buy some extra food, fill fuel canisters and make sure all the science cargo arrived safely.

To get to Kulusuk, we go through Reykjavik, Iceland. Clem and Ludo got an extra day in Iceland because they had a boomerang flight. “Boomerang flights”, common in the polar regions, happen when a plane takes off for a location and then the weather takes a nasty turn, so the aircraft has to return to its point of origin. So you take a long plane ride but end up right back where you started – that’s one of the reasons we plan lots of extra days in our schedule for delays.

Beyond getting people to the field, we have to make sure all of our gear is there as well. Our gear was shipped the first week of March – different shipments were sent from Kangerlussuaq (Greenland), Greenbelt, MD, Salt Lake City, UT and Madison, WI. We have about 4,000 lbs of gear, including the science equipment, camping equipment, generators, and food. Jay, Clem and Ludo have confirmed that everything arrived safely except for our deep drill, which, proof of Murphy’s Law, happens to be one of the most important pieces of gear. We knew it had been delayed in shipping for a few weeks and right now, it’s in Kangerlussuaq, waiting to get on a plane to Nuuk and then onto Kulusuk. Hopefully it will arrive Tuesday, but the latest news is another delay due to airplane maintenance that canceled the flight to Nuuk. There are still two flights that could get the drill there in time, so we are watching this closely. If the drill does not arrive in time, we will have to delay the field work.

Right now the weather is beautiful in Kulusuk, so hopefully all the pieces (people, gear and weather) will come together for an on-time field season. Now I will board a plane, hopefully get some sleep, and send my next update from Greenland.

By Lora Koenig

I am feeling a little sad as I write this post. I always do when writing the last post of a research season. Being able to share my science is one of my favorite parts of my job. I assume some of you looked at our blog’s photos and thought “they’re crazy,” while others started planning how they too could get to Antarctica. Either way, I hope you have found this blog interesting, entertaining and inspiring and that you learned a bit about how we measure snow accumulation in Antarctica.

For some quick updates: Jessica, Randy, and Clem are back home in Utah, Michelle is on her way back to Copenhagen, and Ludo and I are back at Goddard Space Flight Center in Maryland. Our radar gear has already arrived from Antarctica and has been packed away in the lab to wait for another season. Our ice cores made their way from WAIS Divide Camp to McMurdo a few weeks ago but it is uncertain if they will make it back to the U.S. this year: There has been a problem with the ship going to McMurdo, which just passed an inspection in New Zealand and is now making its way to Antarctica. We are hopeful that the cores will make it on the ship northbound but have been told not to expect it. Just another example of the logistical difficulties of working in Antarctica! If the cores do not return this year, it will not affect the science, just our patience. The cores will stay in a freezer until the next ship comes in February 2013. But we’re keeping our fingers crossed that our cores are loaded on this year’s ship.

My next field season, and therefore field blog, is not set right now but please continue to follow online the work that my colleagues and I do at our lab’s website, on Twitter, and through the NASA Visualization Explorer app for the iPad. Results from this research will be posted through those outlets.

Also, the complete collection of our expedition’s blog posts is here.

Until next time, stay warm!

By Lora Koenig and Jessica Williams

Most members of the traverse team have made their way safely back to the U.S. Everyone took a few days to enjoy the summer sun in New Zealand and defrost before returning home. Jessica submitted this blog post and photos from the traverse, with all the scientific details on how we drill and use our firn cores to answer the following question: Is accumulation, or snow fall, changing across West Antarctica? The photos show how we drilled and processed the cores in the field and are the first set of pictures from the traverse. Next week, we will get up more photos of the camp, radar, and the Christmas storm.

Here’s Jessica:

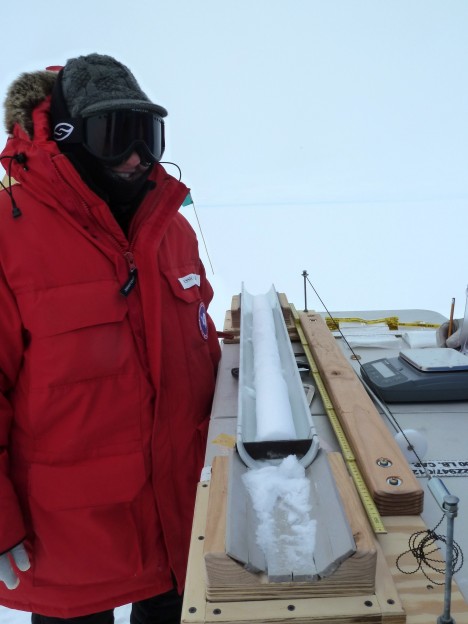

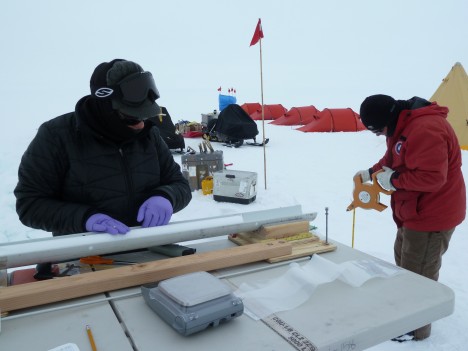

As a reminder to those following the blog, the end goal for drilling the ice/firn cores is to correlate the cores with the layering we see in the radar. (Firn is year-old snow; it’s more compacted than fresh snow but it’s not ice yet.) The radars illuminate layers that can be counted like tree rings, but those layers can sometimes be misleading, recording an individual storm event which is not a complete record of yearly accumulation. We use the physical and chemical properties of the ice core to precisely date the radar layers. Our team collected nine firn cores over a range of low to high accumulation sites this season.

The drill barrel is almost a meter long, so we sample the firn cores in increments of 75 to 90 centimeters (29 to 35 inches), and we collect about 25 increments at each site – that gives us a total sample depth of about 17 meters, or 55.7 feet, which should be equivalent to about 35 years worth of snow accumulation data, depending on the accumulation rate at the given site.

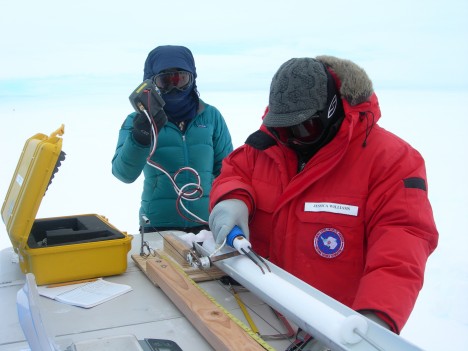

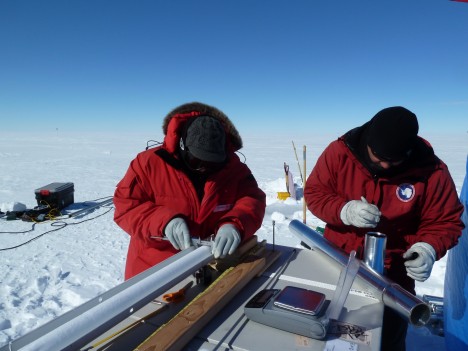

Drilling isn’t a fast process. It takes us several hours to collect a core because we have to do some processing in the field. For each core section, we have to lower the drill into the ground until it reaches the desired depth, and once it’s done drilling, we have to pull it back up again; the deeper the hole, the longer it takes us to do this. Randy was the lead driller. He heaved the 40-lb (18-kg) drill up and down the hole for every core. He is now ready for a strongman competition! Additionally, we have to dissemble the drill barrel for each core section, to get the core out, and then we have to clean the barrel before collecting more sections.

We do some processing of the core sections in the field, and we do it differently depending on how compact the core looks. The upper meters of core are loose and are more prone to break along weaker layers, whereas the deeper the core section, the firmer and less likely to break it is. But every core section needs to have the loose snow shavings brushed off the outside of the core before we measure its bulk weight and length. The length and weight tell us the density of the snow. For the upper meters of core, we do the sampling in the field. We collect electrical conductivity measurements (a measure of the acidity content in the snow) and then we cut the core into 2-centimeter (0.8-inch) thick samples that we then measure for multiple thicknesses and diameters and bag into individual whirl-pak bags (we can measure the weights of these samples in the lab, seeing as they won’t change). Having the thickness, diameter, and weight values for each 2-cm sample is important because we can then calculate density using those parameters (the density of snow increases with depth).

We don’t do all this field sampling for the lower 14 meters (46 feet), which is great because your hands get very cold doing the field processing. For the lower portions of the core, we simply brush off the loose snow shavings and record bulk weight and length. After those measurements, we place the full core section in lay-flat tubing and then slid it into an insulated silver tube and put it in a snow pit to keep it cool and out of the sun until the entire core is complete. We can then wait to perform the remainder of the sampling measurements in the lab.

The entire procedure of drilling and processing a firn core takes about six hours when there are three people working together (one drilling, one handling cores, and one recording the data). Randy was the driller, Michelle the handler, and I was the recorder. Once we collect all of the core sections in the tubes, we place them in insulated boxes with the individual bagged samples and a temperature logtag (records the temperature from that point until we get the cores back in the lab several months later – that way we can validate that the cores were well below freezing during the transport). We bury these boxes in a snowpit under a pile of snow to protect them from UV radiation until they are collected and stored into the ice core freezer at the WAIS Divide field camp.

You will have to wait for Ludo’s blog to read about the recovery of the cores and transport to WAIS Divide field camp with a Twin Otter aircraft.

From the freezer at WAIS Divide the cores will then be transported by boat to the US and then to Brigham Young University, where we’ll complete all the lab measurements. In addition to the electrical conductivity and density measurements for every 2-cm sample, we’ll analyze oxygen and hydrogen isotopes that vary seasonally and are used to date the layers in the core. Using the density, layer depth and age, we can determine the accumulation rate for each core and then compare it with the radar. We are just getting in the preliminary results from last year’s cores now so with some luck, we’ll have the first preliminary results from these cores by next fall.

By Lora Koenig

Greenbelt (MD, US), 3 January — On December 28 in Antarctica (which corresponds to Dec. 27 back here in the States), the team completed the traverse and arrived back at Byrd Camp with a warm welcome from the camp residents. In 18 days they had traveled 500 kilometers (310 miles), drilled eight ice cores, dug six 2-meter (6.56-ft) snow pits and set up and broken down six camps sites. And, I am guessing here, but I am sure they heaved over 20,000 shovels of snow and lifted over two tons per person while moving the science equipment, food and gear around. Ludo shoveled the most, digging the snowpits, and Randy lifted the most, hauling the ice core drill up and down while pulling each ice core to the surface. Most importantly, the team completed all planned science activities and returned safely.

The team arrived Byrd Camp at 10 AM and immediately started packing their gear in order to catch a flight out the next day. Yes, more lifting. It was going to be a very quick turnaround but the rule in Antarctica is, if a plane is on the ground, get on it! The team, along with the camp staff, had the pallet of gear built by the evening and got to enjoy a big meal from the Byrd Camp chefs. They found out early on the 29th that they would not be getting a plane that day — there had been a medical emergency somewhere else in Antarctica and the plane had been diverted there to help. No one is ever frustrated in situations like these; everyone just hopes for the best for whoever was in the incident and waits patiently for the next plane.

The next plane to McMurdo was scheduled for Jan. 2, 2012 (New Year’s Day in the States). This gave the team plenty of time to rest their arms and backs and recover from all their hard work, and gave the weather a chance to allow the Twin Otter at Byrd to retrieve the cached ice cores and empty fuel barrels at the camp site. The cores were collected and taken to WAIS Divide Camp, where they will stay in a freezer (a giant dug-out snow cave) until mid-January, when they will fly to McMurdo on a cold-deck LC-130 flight (a flight with the heater turned off). Once in McMurdo, the ice cores will wait in a freezer until the resupply ship reaches the station in February. Then they will be loaded into the ship’s freezer and sailed to Port Hueneme, California. At this point, they will be put in a freezer truck and driven to the lab in Provo, Utah, at Bringham Young University. The ice cores have a long journey ahead!

The team rang in 2012 at Byrd Camp, which only about 35 other people can claim they did, and on Jan. 2 they left for McMurdo, arriving very late that same day. I talked with the team briefly on the phone when they were in McMurdo, but they were very busy. There was a flight out at 2 AM on Jan. 4 that they were scheduled to leave on. They were all busy cleaning and returning gear, packing and shipping the science equipment back to the States and getting ready to leave Antarctica for Christchurch, New Zealand. I expect to hear if the team has arrived in Christchurch later today or tomorrow. If all is on schedule, the team is just leaving Antarctica and flying over the Ross Sea. Christchurch has been experiencing a swarm of earthquakes over the past few days but there has been no damage that would delay the team’s return. Once the team is settled in a location with good internet connectivity we will start posting their blog posts and images from the traverse, so stay tuned!