By Clément Miège

Hi there! Today I have another story to share with you! It’s about the tracking of the temperature evolution of the firn aquifer temperature by using two thermistor strings that we set up in the two holes made by Jay (see Jay’s post on drilling for details).

By tracking temperatures over a year, we will observe the firn heating mechanisms in the summer with the melt from the surface of the ice followed by water infiltration in the firn. In the winter, we will get a sense of the refreezing processes from the cold surface air, which cools the upper part of the firn and we will observe the persistence of the firn aquifer over the years.

To achieve this, we installed two thermistor strings with two different lengths: 30 and 60 meters. The shorter string has 60 sensors on it, sampling every half-meter. The longer one will only get a temperature reading every 2.5 meters but it will record deeper temperatures. Both strings are set to collect data every hour for an entire year, assuming the batteries last that long (hopefully!) The temperature chain is called a thermistor string because each sensor is a thermistor, a type of resistor sensitive to temperature changes. After measuring a resistance change, calibration curves allow us to retrieve temperature changes.

The thermistor-string story started in Utah, when we received the equipment late from the manufacturers, giving us only 5 days to work on it before leaving for Greenland. We realized that integrating the whole system together with the satellite uplink would take most of our last prep days.

It was definitely too late to ship the thermistor equipment with the rest of our gear, so Rick and I traveled with it in our checked luggage! I ended up with a 50 lbs of spool coiled with about 60 meters of cable in a suitcase. Rick had a black pelican case as his checked bag, with the second thermistor string, datalogger, ARGOS antenna and other pieces of hardware. We learned how to travel light, bringing minimal clothing, and wearing the cold-weather clothes in the airplane so we were able to meet the airline luggage restrictions – it definitely made for fun travels!

At the Kulusuk Hotel, in southeast Greenland, we finished integrating the thermistor string, mostly by picking the right data-transmission rate to the satellite in regards to our battery consumption estimates. Having the ARGOS satellite uplink will let us receive temperature data via email every day from the field site and tell us almost in real time what the temperatures are in the two holes.

In the field, shortly after drilling each hole (to avoid water refreezing due to cold air down the hole), we lowered the thermistor string down and backfilled the hole with surface snow. Then, we used the Felics drill to make a 4-meter hole to anchor the long pole that holds the ARGOS antenna.

On that day, the 20-knot katabic winds were blowing a lot of snow, so we used a mountain tent as a snow-proof environment to work with the electronics before dropping off the case in its hole. To give you a taste of the wind speed: Rick was charging one of the thermistor-string battery and the wind was so strong that it blew the small 1kw generator off…. crazy! When the winds finally died down, we buried the case in a 2-meter deep snow pit, because we wanted to prevent the case from being exposed to surface densification and melt during the summer.

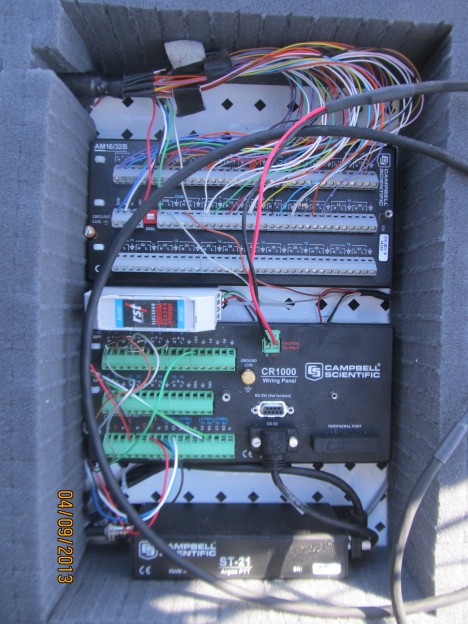

Last check on the electronics, to make sure all the wires are tightened before closing the box — next opening in one year!

After backfilling the snow pit, the only evidence at the surface of the temperature strings is the top of the pole with the ARGOS antenna and a red flag!

We are hoping to recover the case with the datalogger next year, but we are not sure if the ARGOS antenna will still be sticking out, because this sector of the ice sheet is getting a lot of snow accumulation in the winter. We will use a metal detector to find the metal pipes left near the case.

Because this is likely my last post for this expedition’s blog, I would like to thank the all team for this great adventure and everybody that was supporting this exciting research. Until next time!

By Lora Koenig

Well, I am back in Greenbelt, Maryland, typing with warm fingers in a climate-controlled office with high-speed Internet and drinking fountain just down the hall. After fieldwork, I am always thankful for things I generally take for granted, like being able to charge my laptop by simply plugging it into an outlet. There is no longer a need fill a generator with gas and then start it just to charge batteries. Aw, the comforts of home! (We all had safe trips back to the US and have returned to our home institutions last week.)

For the last blog post of the season, I decided to pull together a few of my favorite photos from our trip to give you a sampling of the great fun we get to have while doing this kind of research. The most fun I had during this trip was on our final day in Kulusuk: we were invited to the Kulusuk School to with the children in the upper grades (who speak some English) about our work. I regret that we do not have any pictures of this event, but we were giving our presentation and letting the students run our small ice core drill, thus neglecting picture taking. The school in Kulusuk has about 70 students and includes all grades. The building has lots of windows and is very bright inside — it is one of the prettiest schools I have been in, with lots of open space, a small kitchen, library and a gym. I especially liked the entrance to the school, which was equipped with plenty of coat hangers and boot racks for the students to shed their cold weather gear as soon as they come inside. Though we were there talking about science, the school in Kulusuk is known for their art. We were hosted by the art teacher, Anne-Mette Holm, and after our talk got to attend one of her classes where the students were making wooden sculptures. We also got to see other student projects including weaving, toy making and furniture making. Quite a portfolio! The students’ art has traveled the world, being shown at different expeditions across the Arctic. (Check out pages 11 -15 of this document for some examples of the children’s art work under Anne-Mette’s tutelage.)

While our visit to the school was definitely the top highlight of the trip here are a few others highlights in pictures.

Seeing mountains from our campsite on the ice sheet, a nice change from the typical flat white ice sheet.

So those were some of the highlights of the field work and now it is time to work with the data we gathered. In the week we have been back, we have already started to analyze our data. We see that, as expected, the densities in the firn (aged snow) above the aquifer are higher than expected and that there is more water than originally predicted. We still need more data to fully understand what this water trapped in the Greenland ice sheet means for sea level rise. We need many years of data to understand how and if the aquifer is changing with time… but remember this was an exploratory mission. When we set out, we were not even sure if our drills would even work. There was a chance they would have just frozen in place and we would not have gotten any data. This was a high-risk mission due to the weather in the region and all the new things we were trying. We came back with all the data we set out to get and, quite frankly, I am surprised. We had a large team that helped with this project including the field team, logistics support, airport support, the NASA and NSF support teams and all of you for your well wishes and interest in our research. Thanks to all! Until next time, stay cool 🙂

By Ludovic Brucker

We were on Greenland’s ice sheet for only a week, but despite the short deployment, we had to accomplish two main science objectives. The first was drilling two deep cores into the firn (aged snow) and ice (30- and 65-m deep, respectively), to insert temperature probes that will record temperature evolution at various depths. Secondly, we wanted to drill shallower cores (7 to 15 m) to record the snow’s density vertical profile using a neutron density probe – and this is what this post is going to be about: the shallow drilling that we did and the measurements we took in these holes to monitor the snow and ice layering and their properties.

To drill the shallower cores, we used the same solar-powered drill as in 2010 and 2011 in Antarctica during the Satellite Era Accumulation Traverse. It is composed of four parts, which I’ll describe from top to bottom. The first segment contains the motor to rotate the other parts. The second and third parts are barrels — one for the snow and ice chips, and the other to store the one-meter long drilled core. The fourth part, the cutters, is screwed into the latter barrel. Cutters are critical since they are the sharp elements that cut the snow, firn, and ice. Since snow and ice having different properties, the cutters for snow and ice are different. For instance, if we use the ice cutters at a smaller angle, we will drill at less depth during each barrel rotation. Where we drilled, part of the winter snow melts during the summer and when it refreezes, it forms a thick ice layer every year. The snow that did not melt will slowly evolve to firn, and, eventually, ice. Because of the different, we thus had to switch cutters during our drilling: otherwise, we would have not been able to drill through the past summer ice layers.

Jay drilled cores through the water contained within the firn (the aquifer). We used our smaller drill, since we did not want to enter in contact with the aquifer. Therefore, each of our cores was shallower than the water layer’s top and each was drilled in about an hour.

Once we had drilled the hole, we observed the layering of the snow and ice cover using a video camera. Thanks to the camera’s flashlight, we were able to identify the thick 2012 summer ice layer (about 3 m below the surface) that formed after a massive surface melt event, as well as the previous summer ice layers. Our team used this sensor to monitor a water-filled hole for the first time. We were all really excited to see the inner upper part of the ice sheet!

Lora holding the video camera that she will send down in the hole to monitor the snow and ice layering.

We also used this useful device to check the position of the temperature probes and to ensure that the entire line of temperature sensors was straight inside the hole. The first time we inserted the camera into the water in the hole, we were amazed to discover the amount of air bubbles released by the firn, which propagated toward the water/air interface. The aquifer is composed of ice, water, and air. These elements are present several meters below the surface, which means they’re under pressure. Once we drilled the cores, the pressurized air bubbles in the vicinity of the hole migrated toward the hole and then moved upwards to the water/air interface.

Our last scientific activity was to monitor density with 1-cm vertical resolution using the neutron density probe. We moved the probe along the borehole at a speed of about 5 cm per minute. This sounds like a time-consuming measurement, but measuring density manually is significantly more labor intensive since one must saw the core into segments and then measure each segment’s length, diameter, and weight.

To be more comfortable during the drilling and while recording our scientific data, we always paid particular attention to staying behind our wind break.

Lora and Ludo drilling behind a windbreak during a windy day, with a lot of blowing snow near the ground.

A windbreak is composed of a simple plastic tarp supported by bamboo sticks and held by bungee cords. While we were in Kulusuk preparing our departure to the field, Jay told us several times that bamboo sticks would be critical pieces of equipment while we worked on the ice and that they had to be in mint condition to offer the best resistance to wind. So we spent more than a day in Kulusuk fixing and reinforcing bamboo sticks, using wires and tape. And I am glad we did it!

Once we had collected all the data needed from a hole, we packed our equipment, removed the precious windbreak and the bamboo sticks, and either headed toward a new site few hundreds meters away, or went to the cook tent for diner. That’s how our busy days in the field went!

By Clément Miège

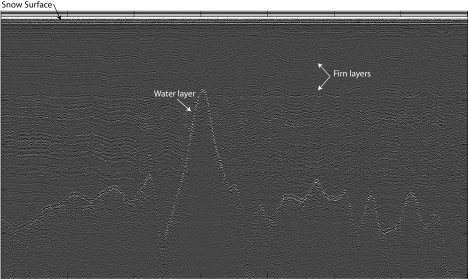

Hi there! Today I will give you some background on the radar measurements we collected in southeast Greenland. The radar we deployed is sensitive to snow density changes and to wet snow. The main goal of the radar measurements was to provide information about the spatial variations of the top of the aquifer (a water layer trapped within firn, or old snow).

The radar we used is made by GSSI, a company specialized into geophysical measurements, and it has a center frequency of 400 MHz. In snow and firn, the electromagnetic waves sent by this ground-penetrating radar can image approximately the first 50 meters of a dry snowpack. The layers that we observe in radar measurements show the snowpack stratigraphy (density changes). If there is water within the snow and firn, we observe a really strong radar echo in the radar profile. Then, by dragging the radar around, we are able to see how this water layer evolves spatially.

Here is the radar system in action, with Ludo pulling the sled. It can be a pretty tiring job with the wind and the cold. The balaclava was an absolute must to protect your face from the freezing temperatures.

Mostly to lighten our helicopter loads, but also to exercise a bit, we decided to pull the radar sled with skis. But it ended up not being an easy job at times: some of our field days were really windy and cold, so we needed to be warmly dressed and have our face well-protected. In addition, we carried a backpack with the GPS unit and a battery – they became pretty heavy after an hour of pulling the radar. Ludo and I set up the rule of not doing more than 2 hours of survey at a time, which corresponded to about 5 km total.

Once on the ice sheet, as soon as the helicopter took off, we turned on the radar. Indeed, we wanted to make sure that we had been dropped over water and then find the best location for our drilling site. By looking at the radar profile, we identified the water layer (great!) and we converted its depth from electromagnetic wave two way travel time to meters. We observed that over a 2-km transect, the top of the aquifer varied up to 10 meters. By knowing this variation, we were able to pick the site location at a depth that fitted our science needs.

An example of the radar profile observed: the bright reflector represents the top of the water layer. Other internal reflections can be seen — they are linked to previous summer layers, which are denser.

The advantage of doing this preliminary radar survey is that we then knew before drilling at which depth the drill would encounter water and penetrate into the aquifer. And the good thing was that the radar picked the right water depth in both drilling sites! The radar ended up being a really good tool to extend spatially the localized information obtained by the firn cores.

For the radar survey, we were doing some elevation transects, to see how the water layer changed with the local topography, and some grids and bowties to extent spatially the core site stratigraphy. We stayed within a radius of 2 km from our camp.

Overall, doing the radar surveys was a great experience. It’s incredible to think that we were skiing with liquid water right below us, while surface temperatures averaging -15C.

Finally, concerning the radar setup, we have already some improvements in mind for the next time. For example, the GPS unit and its antenna need to be in the sled, maybe mounting the GPS antenna on a corner of the radar sled, trying to keep the all setup stable. That will allow us to drag the radar longer. We will work on that for our next radar adventure!

By Jay Kyne (Greenland Aquifer Team’s driller)

At first we all talked on the phone about it. And then I saw the picture: another driller had drilled into water and, as the drill hung on the surface, there was water dripping from it. Of course that drill quickly froze. So the question was: how do we drill thru the cold snow on top and then into the wet, warm snow/ice below it?

I’ve been drilling into the Greenland ice sheet for nearly 25 years, but I never imagined that there was water down there that didn’t freeze over the cold, dark winter. There have been some deep holes drilled way out in the middle of the ice sheet, all the way to the bottom (about 2 miles deep) and there at the base of the ice sheet the temperatures are near freezing, but not quite there: heat is coming up from the earth, warming the underbelly of the ice sheet. But the newfound aquifer was water that came from the top, melted snow that percolated down the ice. That was surprising to find out, but now the question was how we were going to drill through it.

They told me that their radar showed that the water was between 12 and 25m below the surface. I’ve drilled a lot of holes to that depth with a small lightweight drill that I turned from the surface with a big electric drill. It’s basically a tube with helical plastic strips attached to the outside and cutters at the bottom end. You have to come up about every meter and take the core out and dump the snow cuttings, or “chips”, as we call them. As you get deeper, you add more stem to reach the bottom.

I’ve also drilled ‘warm’ ice with a drill that melts its way down, but that was in the continental United States: in Wyoming, Washington and California. That ice was right at freezing temperature.

So we decided to use both of these drills and make the switch when we felt the time was right. And it worked! It was fun working with the Greenland Aquifer Team, too.