By Lora Koenig

Byrd Station (Antarctica), 9 December — Today was a huge day. First off we figured out the problem with the radars: One of the USB ports on the computer was not functioning properly. When we changed the USB port, the problem went away. I was relieved there was such a simple solution to the problem and so was Clem, who had had a rough night’s sleep worrying about the radars.

At around 9 AM we headed out to drill our first ice core of the season. We drilled at a site about 3 kilometers (1.86 miles) away from camp. This site was chosen because a previous ITASE core was drilled there in 2002. Our core will update this core and we will compare the overlapping years of ours with ITASE’s to understand any differences. Last year we also drilled at a site of a previous ITASE ice core and got similar results that give confidence in the measurements and methods from both cores.

Clem ran the radar out to the drill site to image the layering while Ludo drove the snowmobile. Once at the site, Ludo immediately started digging the snow pit to sample the snow in the top 2 meters (6.56 feet) of the ice sheet. The snow at the very surface of the ice sheet is very similar to the hard wind-packed snow that you would encounter in the high mountains in the U.S. and it’s not bonded well enough for us to ship cores of it back to the U.S. in one piece, so instead we took samples of the snow in the pit for lab analysis. The cores have to stay in one piece, or we would lose our chronological record. Additionally, we took other measurements in the snow pit that are important for modeling how the microwave radiation, from both the satellites in space and radars on the ground, interacts. Snow grains of different sizes and shape can actually be detected by satellites in space! As the snow grain size changes, the signals in space change.

Ludo spent all day in the pit. We think he may hold the record for the most time in one pit, about nine hours from digging to fill in. He took infrared photographs of the snow. Here is one from the pit:

These photographs are used to calculate the grain size given the different reflectance levels of the infrared radiation. The photos are pink because they are taken in the infrared wavelength, not visible light like most cameras do. They are also very pretty to look at and you can see all of the layers of snow. Each storm puts down a new layer of snow. There was a new layer approximately every 6 cm (2.36 in) in this pit. There were more layers than I have ever seen before in a pit, which made the pit measurements take such a long time.

At about a third of the way down the picture the snow becomes firn, which is snow that had persisted through at least one melt season. We cannot tell from the snow pit exactly how old the firn in the pit is (we need the isotopes for that), but we know that there are at least three years of records in the pit, so the firn at the bottom could be from 2009.

After the infrared photos, Ludo recorded the stratigraphy of the pit (snow grain size and type) using a macroscope, cut snow samples for isotopic analysis, and measured the thermal conductivity of the snow, which is the snow’s ability to transfer heat. Heat conducts through the ice lattice more than through the air in the pore spaces, so thermal conductivity is also a measure of how bonded the snow is. Because I was helping Ludo in the pit there are not any photos of this process. Often while we are actually doing the science we don’t have many photos because we are all working.

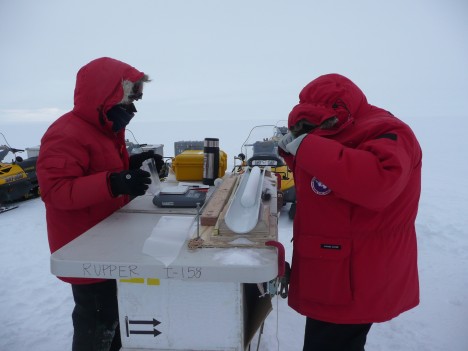

As Ludo was working in the snow pit, Randy started drilling the ice core. He would drill the core and Jessica and Michelle would process it. The core is weighed and measured to calculate its density. The length of the core and the depth of the drill hole are recorded, and the electrical conductivity of the core is measured to detect changes in snow chemistry. The core is then put in a bag, a tube and a box for shipping back to the lab for isotopic analysis. The final depth of the core was 16.8 m (55.1 ft), which will correspond to about 40 years of snow accumulation history.

By Bob Bindschadler

McMurdo (Antarctica), 12 December — Well, nearly a week has whizzed by. We have been quite busy, but it doesn’t feel like there’s been much real progress. Every day seems to come with its own set of new problems and developments. This includes cargo hunting (yes, it was still going on until recently—but it’s DONE now), remembering some item or tool that would probably prove useful (then finding it and getting it) or thinking of some small thing to build and then getting the carpenters or machinists to understand what we want, (then waiting for the item, packing it and getting it into the cargo system.)

Tying up these loose ends didn’t add much weight to our overall cargo load, but we knew we were going to be heavier than we had planned for because there were some heavy items that failed to make it on flights to Byrd Station, where the over snow traverse was going to be taking them to the main camp at Pine Island. These problems originated way back in early September: Early season weather in West Antarctica was worse than usual, which meant fewer flights to Byrd and less of our cargo getting there when the traverse needed to start. Without sufficient cargo, the traverse managers held their departure back a few days. When they tried to start, one of the large tractors failed, leaving them with only three. This actually worked out better, since there was less cargo to pull. Now we hear that the traverse is encountering soft snow, slowing its progress even more. The image below is a map of the traverse’s progress through last night. It’s averaging less than 4.5 miles per hour and under 60 miles per day: At this rate, it will be another five days before it arrives at PIG.

It’s a polar tortoise and hare race. The traverse is undoubtedly the tortoise, but the hare is having its own difficulties. Flights to PIG take “only” 5 hours (one-way) and were scheduled every day since Wednesday last week (except Sunday). Each one of them was cancelled because of bad weather at one or more of the required landing spots: McMurdo, Byrd or PIG. Good weather at Byrd is necessary to refuel the plane on its way home. Today’s weather looked the best of all days and, unlike last week’s flights, the plane actually took off from McMurdo. But two hours into the 5-hour flight, the weather went bad at Byrd. WAIS is another nearby station that could refuel the aircraft, but weather also went bad in there not long after. So the plane was ordered back to McMurdo before it was so far away and had so little fuel that it would get stuck somewhere out in the middle of West Antarctica.

It’s anybody’s guess who will get to PIG first: the traverse or the put-in flight. The traverse is more important, because it has the heavy equipment to dig out all the camp material left there at the end of last season (a small camp was set up then), groom the runway used last season (if the flags marking it can be found, that is) and tap into the all-important fuel bladder. Getting to that fuel is key because with it the LC-130 cargo planes (called “Hercules” or “Hercs”, for short) can get enough fuel to get back to McMurdo without having to stop at Byrd or WAIS. This will make missions to PIG less susceptible to weather cancellations.

Our cargo handling is done. But, as I mentioned, since now we have to fly some items that didn’t get to Byrd by the traverse’s departure, our stuff weighs more than planned. Whether that requires another flight will not be decided until we hear if the groomed runway at PIG can handle heavier landing weights. It’s all connected: cargo, tractors, fuel, airplanes and weather. Meanwhile, we will make our case for moving our necessary science cargo up in the queue, so we don’t suffer more delays.

It’s not all bad news. These past few days have contained some bright spots. Our project has received a lot of attention. A Blue Ribbon Panel, here last week to assess the effectiveness of the US Antarctic Program, really likes the social relevance of our mission and its interdisciplinary character. I gave a science lecture on PIG to a packed audience and got superb reviews. Many people here have touched the project in one way or another and I wanted them to understand what it was about and why we have to go to someplace that is so hard to get to. I also was singled out to prepare a poster and speak to the Prime Minister of Norway, who is flying to the South Pole to mark the 100th anniversary of Roald Amundsen’s trip.

Attention is great; more progress would be even better!

By Bob Bindschadler

McMurdo (Antarctica), 6 December — Stuff, stuff and more stuff. When you have to take everything with you to a remote place, you end up with a lot of stuff. When you add to that the equipment necessary to make the measurements we intend, the pile of stuff gets even bigger. That’s what we’ve been doing that past few days: piling up stuff.

I mentioned before that many items we sent down to Antarctica were found in various locations around town. Finding each item was followed by getting the right label for it (with a unique tracking number), so once the label was attached, it could be moved to a common location. That is where our pile of stuff is now. After talking to the right cargo people here, looking at their documents and comparing their lists with ours, we are pretty sure that the stuff we can’t find in McMurdo took an early 1,000-mile flight to Byrd Station, where a glorified polar tractor will drag it on a sled for the remaining 400 miles from Byrd Station to the PIG Main Camp. This is not an exciting trip; the traverse participants lumber along at about 5 miles an hour and it takes them 7 mind-numbing days to complete the trip. They then will leave their loads, turn around and repeat the journey back to Byrd. What is exciting about this traverse for us is that with yesterday’s successful flight to Byrd, the traverse party has enough material to get underway. So the project is finally taking the next step toward PIG—at 5 miles per hour!

Meanwhile, back in McMurdo, our task is to pull together the variety of other stuff we will need at our camp. Our cook, Jake, is handling all the cooking and eating stuff. We are checking tents, sleeping bags, radios, satellite phones, GPSs, shovels, ice screws, safety harnesses, ice axes, snowmobiles, generators, battery chargers, chainsaws,… The list is pretty long and detailed. McMurdo is well stocked with these types of items because many different field parties draw on this inventory. Those hearty souls that spend the entire winter at McMurdo do an excellent job of cleaning and repairing and preparing this equipment for summer field parties. We take our portion, pack it, weigh it, document it, label it and add it to our pile of stuff.

The next, and bigger step toward PIG may come tomorrow. The put-in flight is scheduled for a morning departure. It takes over 5 hours to fly there on a LC-130 (the “L” means it is a modified C-130 cargo plane—the modification is the inclusion of skis that straddle the regular wheels). The forecast is not good—40-knot winds now, increasing through the night. However, after that storm passes, the winds are expected to die down and we could have a day (or two? Please make it two!) of clear, calm weather there. Only five people are going to be getting off the plane if it makes it in. They will set up communications, erect a small communal tent and start the process of digging out the camp material left there at the end of last field season. It’s their stuff.

P.S. You can view the PIG Main Camp site through daily photos taken by two web cams we set up last year.